You can trust VideoGamer. Our team of gaming experts spend hours testing and reviewing the latest games, to ensure you're reading the most comprehensive guide possible. Rest assured, all imagery and advice is unique and original. Check out how we test and review games here

It’s that time of year when critics, like Santa, start making lists—though I’ll be damned if I’m checking mine twice. For me, the end-of-year stock take usually consists of scraping my memory to see what has stuck, like gum under a seat. This is far less gross and far more rewarding than it sounds. So many games arrive amid squalls of marketing, or the steadily toxifying fumes of expectation, only to give us very little to chew over, before peeling cleanly from our recollection. My list this year comprises those games that have, for one reason or another, hung around. Of course, this is not the only criteria. There are plenty of games, after all, that were unforgettably bad; I will struggle to shake the towering, well-dressed, and life-draining Resident Evil Village for some time.

So, what else is there? In a word: newness. Only three of the games on my list are sequels; but all ten offered something unseen—a mechanic, an art style, an idea, a theme. Most important, they were all fun. The entries here would make for excellent party guests; they would all have much to say to one another, whether it be naughty or nice, and even the blockbusters would mingle happily, and without hauteur, with the smaller releases. In no particular order, here are some of the best games that I’ve played in 2021.

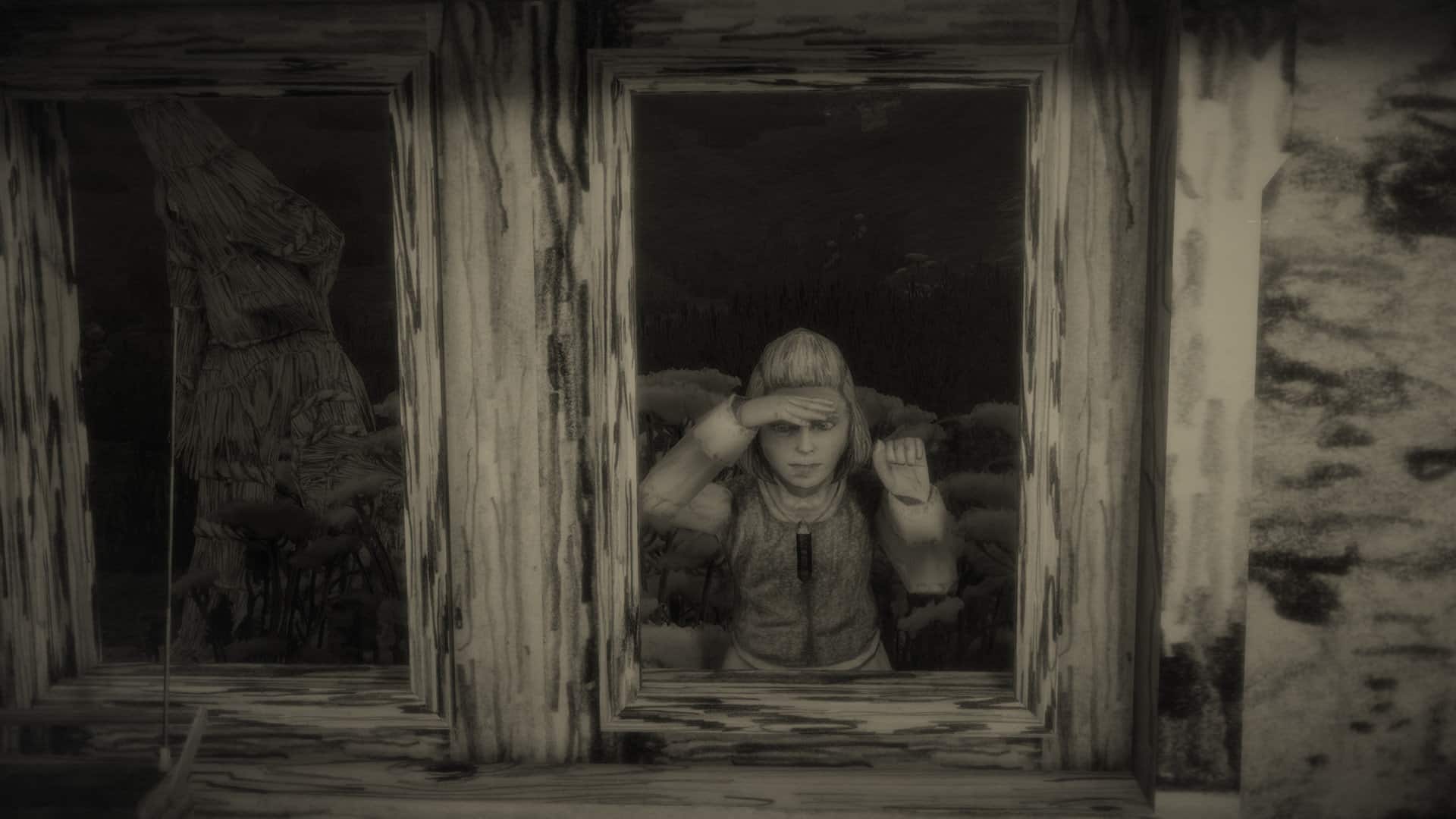

Mundaun

Mundaun is one of the more beautiful games of the year, precisely because its trick is to look rough. The director, Michel Ziegler, scanned his notebooks and pasted the sketches within onto the game’s world. Wood grain is textured with a sidelong rake of graphite, and a young girl’s troubled features are limned in fine pencil. Though the process must have been painstaking, the result feels coarse and immediate, as though Ziegler’s hand were the needle on a Richter scale, and he were merely registering the shocks. The plot follows a young man, Curdin, as he travels to the rural village of the title to bury his grandfather. The problem with Mundaun is that things don’t stay buried for long. Ziegler’s themes are fed by Swiss fables, and bound inextricably to his technique. The devil is in the detail.

Chicory: A Colorful Tale

From lead, we go to paint, much the messier option. On the surface, Chicory: A Colorful Tale is about a magic brush, wielded by a destined soul whose job is to apply bright coats onto a black-and-white land. But who needs surface? Really, it’s about the way that pressure is daubed onto the spirit, and the way that, as our ideas of ourselves dry and harden with time, so, too, can they crack and flake away. The adventure is carved from the template of The Legend of Zelda, and it uses the touch pad of the PlayStation 5 as a canvas, across which you swipe to unleash a blurting swash of paint. The puzzles and bosses are ingeniously beaten with this mechanic, and the towns are crammed with colour-hungry N.P.C.s. But the game’s coup is that it’s just as striking when stripped of its hues. The blank canvas is a wonder; who needs a brush with destiny?

No More Heroes III

It isn’t often that you emerge from a video game having been briefed on the pleasures of the films of Takeshi Miike, rarer still that such a briefing should come across as anything other than a patronising bore. No More Heroes III, from Goichi Suda, offers just such academe; thankfully, it also offers the chance to lop the heads of aliens and bask in the leaping streams of blood. Miike would approve. As a rule, I am a fan of any game that bears the marks of a single mind, however warped that mind may be. Like Hideo Kojima, Suda treats his game like a loft, into which he lugs the wild clutter of his obsessions. But we are never mired in the kind of gloomy longueurs that you often get with Kojima, plunged into auteurnal darkness. Instead, No More Heroes III is a blast, an open-world hack and slash—the combat devotedly slash, the writing admirably hack—baked in sunlight, and the year’s best mood-lifter.

Art of Rally

Art of Rally features rally racing, but it’s also one of those games that is about something. That something happens to be rally racing. As with No More Heroes III, you feel as if you were being dragged through the dirt of someone else’s obsession. The developer, Funselektor Labs Inc., lovingly blurbs the history of the sport in the menus; the world is one of scrubbed-clean surfaces; and the view is pulled back, giving you the impression that you are playing with toy cars—which, of course, you are. The racing itself is punishing, not so much rewarding patience as requiring you to drift yourself—to enter that odd state, riven from the loops of play and floating somewhere above it, just like the camera. And I won’t soon forget the declaration, given in-game by a Buddha Statue, that “To do something dangerous with style is art.” Funselektor would know.

Returnal

In a year hardly short of chronologically cracked adventures—from the tick-and-whir nastiness of Twelve Minutes to the murder-go-round of Deathloop—Returnal stands apart. Its masterstroke is to tease out the fundamental connection between games and temporal repetition; this is, after all, a medium wherein we talk of gameplay loops, and one built on the notion that the words “Game Over” ought to be followed by a proposition: “Continue?” The game’s heroine, Selene, shoots her way through an alien world, in a desperate attempt to do just that. If she dies, she wakes back at the crash site of her ship. The developer, Housemarque, has its heart in the arcade, and Returnal is both a murky science fiction and a sublimely tooled shoot-’em-up: Prometheus meets Eugene Jarvis. After the financial failure of Nex Machina—one of the most exquisite games of recent years—Housemarque published a blog post with the doomy title “ARCADE IS DEAD.” With Returnal, it found a way to continue.

Hitman III

Let us give thanks to Agent 47. Hitman III is likely the last we will see of him for some while. The developer, IO Interactive, will, I guess, be busy with Bond, and our favourite assassin—he of the sanguine necktie and the razored cranium—will elude our gaze for who knows how long. Still, Hitman III was a worthy sendoff; it jetted us, in the midst of a marrow-biting January, to Dubai and to the Burj Al-Ghazali, a lofty stalagmite of glass, as our man went about his work. As much as I miss the downbeat tone of the old games, this series is still the place to go for grownup thrills: clothes, glamour, and effortless globe-trotting. The new game’s collection of levels—six in total, with highlights including Dartmoor and Berlin—form a black-humoured collage of kills. Following this, Bond has his work cut out for him.

Psychonauts 2

Like its sixteen-year-old predecessor, Psychonauts 2 has us hopping into the heads of other people—which was always a morally grey matter. The original grew a cult following, and the writer, Tim Schafer, is wise to the weight of expectation. He takes after his eponymous heroes and treats the new game as a chance to probe the inferiority complex of any sequel. “Memories, my boy. Just a show we put on inside our heads,” someone says to our hero, Raz. Indeed, but what a show! For returning fans, there is more Sasha Nein, more Milla Vodello, and more of Schafer’s vision of the nineteen-sixties—a swinging cartoon, licked with lollipop tones. This is a platformer possessed of ideas and wit; it deals with dark-edged subject matter in the brightest and brainiest of ways, and would rather provide laughs than easy answers. Roll on 2037!

Kid A Mnesia Exhibition

What do you get when you take two of Radiohead’s most sunless albums, Kid A and Amnesiac, along with a boatload of artwork by Stanley Donwood and Thom Yorke, writhing with disquiet and unspecified rage, and cram it all into a virtual museum? The answer—aside from a glum afternoon—is Kid A Mnesia Exhibition. Among other things, it affords the opportunity, denied to fans for over two decades, to watch one of Radiohead’s live shows while sitting with an imp. Elsewhere, we get snatches, sighs, and bursts of the band’s music as we move through this dreamlike space. Spirals of white marble, doors pooled in red light, and even a forest—not unlike the sort that Michel Ziegler would rough out into the ether. Whatever Kid A Mnesia Exhibition actually is (walking sim? Interactive music video? V.R. art gallery?), it delivers the recognisably Yorkian brew of brow-furrowed longing and panic, computerised in a fresh and fitting way, and it leaves you lighter than when you went in.

Deathloop

A three-note guitar riff, a hero with a jacket the colour of burnt caramel, an angry woman with a machete, and a world built to the exact specifications of Ken Adam’s wildest dreams. Such are the delights of Deathloop, from Arkane Studios. The premise is simple: A glitch in time saves nine, and Colt Vahn must undo the glitch by killing eight key targets—plus the angry woman, Julianna, should she choose to show up and spoil his progress. Arkane excels at cleverness, at crafting levels and wiring them like brains, or bombs—filled with memories, ripe for the hatching of plans, and ready to blow at any moment. Deathloop is Arkane at its most reflexive; the studio manifests the theme of repetition—crucial for the full appreciation of games like Dishonored and Prey—as a part of the game’s fiction. After enough loops, you may feel like Julianna: “It’s the only amazing place in an entire world of s***,” she says, of Blackreef. “You’ll see it, eventually.”

Solar Ash

Solar Ash is the second game from Heart Machine, whose debut, in 2016, was Hyper Light Drifter. It tells the story of Rei, a Voidrunner, which, like a Blade Runner, entails the tracking and snuffing-out of several lifeforms; unlike a Blade Runner, however, it also involves futuristic roller skates. The creative director is Alx Preston, who suffers a congenital heart condition, and the game is pumped full of imagery that speaks to that suffering. Needles, passageways blocked with black gunk, and a perfusive sense of the thwarted. In its embrace of movement and lurid colour, Solar Ash brings to mind Jet Set Radio, while its environments—each bound by gravity and shrunk by the sharp bend of the horizon—recall Super Mario Galaxy. Both in its play and in its themes, this is games as a release; no matter the void, living is running.