You can trust VideoGamer. Our team of gaming experts spend hours testing and reviewing the latest games, to ensure you're reading the most comprehensive guide possible. Rest assured, all imagery and advice is unique and original. Check out how we test and review games here

Wolfenstein Cyberpilot is set in 1980. You play as a hacker for the French Resistance, whose job it is to reprogram the weapons of the Wehrmacht and redeploy them against their masters. It’s a simple, devilish idea, burnished by the immersive power of VR. In truth, the immersive power of VR is nothing compared to 36-degree heat, and I think Bethesda knew what they were doing releasing the game this week – this July. As I sat strapped into my PSVR, which is essentially like taping a hot computer to your head, I felt like I was boxed into a breathless machine. I kept blinking the sting of sweat from my eyes and I thought to myself how clever the people at Bethesda are; the only way they could achieve more intimacy would be with the aid of Smell-O-Vision.

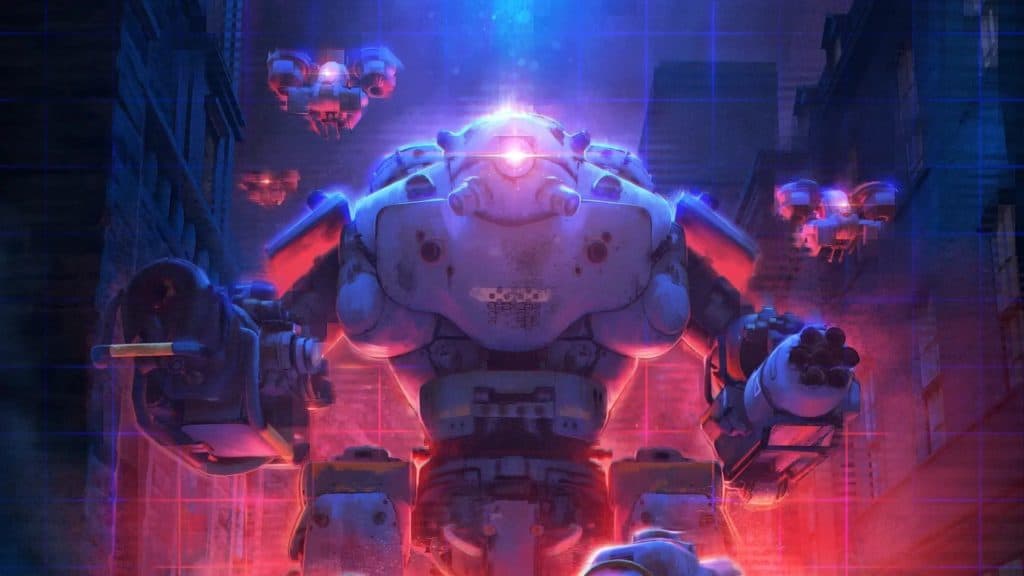

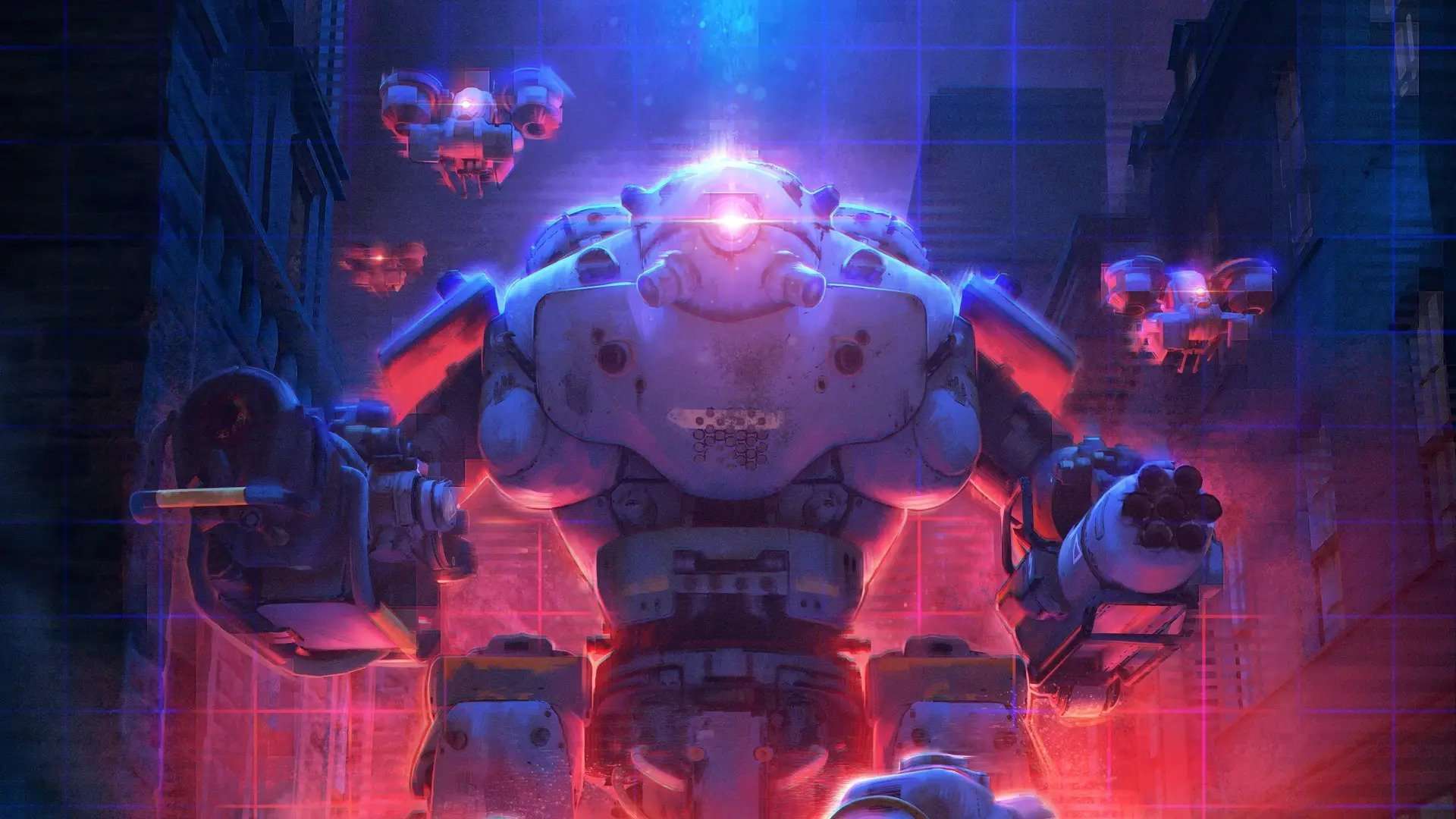

It’s doubly strange, then – and not without a dash of irony – that playing the game should make you feel oddly removed. Granted, this is in keeping with the premise. Like modern-day UAV pilots, you conduct your war in private; working underground, within the concrete fastness of a French laboratory, you never touch the light and the air of the streets above – nor the fire or the blood. However, there is something unintentionally lifeless amidst all the death. The first mission, for instance, sees you clattering through the alleys – which are all charmingly crammed with cafés and bakeries – atop a Panzerhund: a terrifying combination of canine and tank, whose mouth sprays pillars of flame and whose claws thud with terrible weight along the delicate boulevards.

Such a vision outdoes even Disney, when it comes to contrasting beauty and the beast, and it should be one of the more exciting things I’ve done in games this year. But, aside from the pleasing bob of the hound’s head below the crosshairs, there is a static drabness to it all. The German soldiers are all as dumb as dolls, standing still and then, when you’ve char-grilled one of their comrades close by, hopping to and fro, firing limply in your direction, and waiting to receive a roasting of their own. Another mission, which has you flying a drone through the gloomy bowels of a German research facility, opts for a stealthier tack. This amounts to plunging down on a panic button to cloak yourself, hanging just above your prey, and pulverising them with a bolt of lightning.

Far more interesting, and what makes the drone segment the best thing about Wolfenstein Cyberpilot, is the chance to drift over the desk clutter of the Third Reich. As is often the case with VR, it isn’t the explosions I’m drawn to but the ashtrays, the mugs, and the monitors, scrawled with glowing green numbers. The surfaces here aren’t gritted with as much fine-grained detail as, say, Blood & Truth, which gave us clipboards, vapes, and takeaway trays to pore over. Alas, owing to the remote nature of your mission, you can’t actually pick things up outside the lab. I found myself, when the litter failed to draw me in, gazing down at my own virtual hands; Wolfenstein Cyberpilot has, I’m pleased to report, very good hands – gloved, zippered, and scratchy. It’s the only reminder that you are, in fact, playing as a person, and not the robots you hijack.

Not that you’re much of a person. You never speak. You have no name – your handler, Maria, refers to you, with a husky French lilt, as simply ‘Cyberpilot’ – and you spend most of the time possessing moving metal. You could accuse the game of being stark of story, but, to be honest, I didn’t mind that. After Wolfenstein: The New Order and Wolfenstein II: The New Colossus, it’s something of a relief not to inhabit human flesh. The atmosphere of Wolfenstein is bitter and black-hearted. Even the heroes come ready-cruel, hardened by the unstinting brutality they are subjected to and forced to mete out; any skin in these games is indistinguishable from the brushed steel of the Nazi new world. Even the humour – burnt and brittle as coal – opts for archness and irony over warmth of any kind.

‘I’m Jemma. I like poetry and punching Nazis,’ says your A.I. assistant, refuting, with adolescent snark, Adorno’s famous declaration – ‘There can be no poetry after Auschwitz.’ In Cyberpilot, just as in the previous two Wolfenstein games, acts of depravity are carried out with the air of righteous justification – ‘Killing Nazis isn’t just fun and games. It’s necessary,’ says Maria. And if you have a taste for the liquorice-dark drollness of the series, you’ll find much to grin at here. You will also find a curious VR companion to Wolfenstein Youngblood, which takes place soon afterwards and occupies the same space. For me, the initial novelty wore thin as I found myself floating or clomping restlessly towards my objectives, doing whatever was necessary and wishing for more fun and games.

Developer: MachineGames

Publisher: Bethesda Softworks

Available on: PlayStation 4 [reviewed on], PC

Release Date: July 26, 2019

To check what a review score means from us, click here.

Wolfenstein: Cyberpilot

- Platform(s): PC, PlayStation 4

- Genre(s): Action, Shooter, Virtual Reality