You can trust VideoGamer. Our team of gaming experts spend hours testing and reviewing the latest games, to ensure you're reading the most comprehensive guide possible. Rest assured, all imagery and advice is unique and original. Check out how we test and review games here

About a year ago, Nate Crowley (pronounced like the bird, or, if you prefer, the famous occultist) tweeted that, for each like the tweet got, he would make up a fictional video game. It got a lot of likes; Crowley publicly begged people to unlike the tweet so he could finish on an even grand of bogus games — by the end he was slotting ideas together like the manatees that South Park portrayed writing Family Guy jokes: real time strategy with lemons except that when you play it you die in real life. A hundred of these, including Wolfglance Tycoon, Komodo Flagons, and The Greatest Gatsby, have now been made into a book, which Crowley describes as ‘definitely a toilet book’.

If it is, it’s one of the funnier and most well observed of that lofty genre. While the Twitter thread of fictional games is in no particular order, 100 Best Video Games (That Never Existed) is plotted chronologically, starting with the 80s, and references a heady mix of real things, fictionalised versions of real things, and a completely made up history of the medium that links the games together (‘itinerant wunderkind’ developer Oliver Blood and the Moth Expert fiasco of ’83).

This was partly to give the buyer value for money, because Crowley didn’t want to ship a book that was a long list of tweets without context, but it also allowed him to have fun in the process. ‘Concepts for games are quite funny, but what’s also really funny is, like, the development nightmares people get into, and marketing controversies and stuff,’ he said. Talking to Crowley is a similar experience to reading his book, because he’ll be saying quite normal things, and then drop in something funny or peculiar without noticeably changing gear.

I read the book on the tube and would see people looking over my shoulder at the page for, for example, Quadbike Sorcerer or Gorillionaire, and realised how, if you knew nothing about games, the whole book would be quite believable. With some of the entries, like recruitment consultancy building sim Recruitment Barn 2051, I was astonished that they didn’t exist already, and the possibility of a CrowleyJam has been raised. Crowley explained that the balance of fiction and almost fact is very intentional: ‘One of the big demographics for this, I’m hoping, is going to be confused uncles on Christmas Eve, who are like, ‘I’m pretty sure my niece likes those video games. This looks alright; it’s got a pretty cover.’

According to Crowley, being absurd but staying believable is easier to do with games. ‘Some of the biggest hits have been really desperately unusual concepts. Like Sonic the Hedgehog, if you really stop to think about it. You know… What?‘

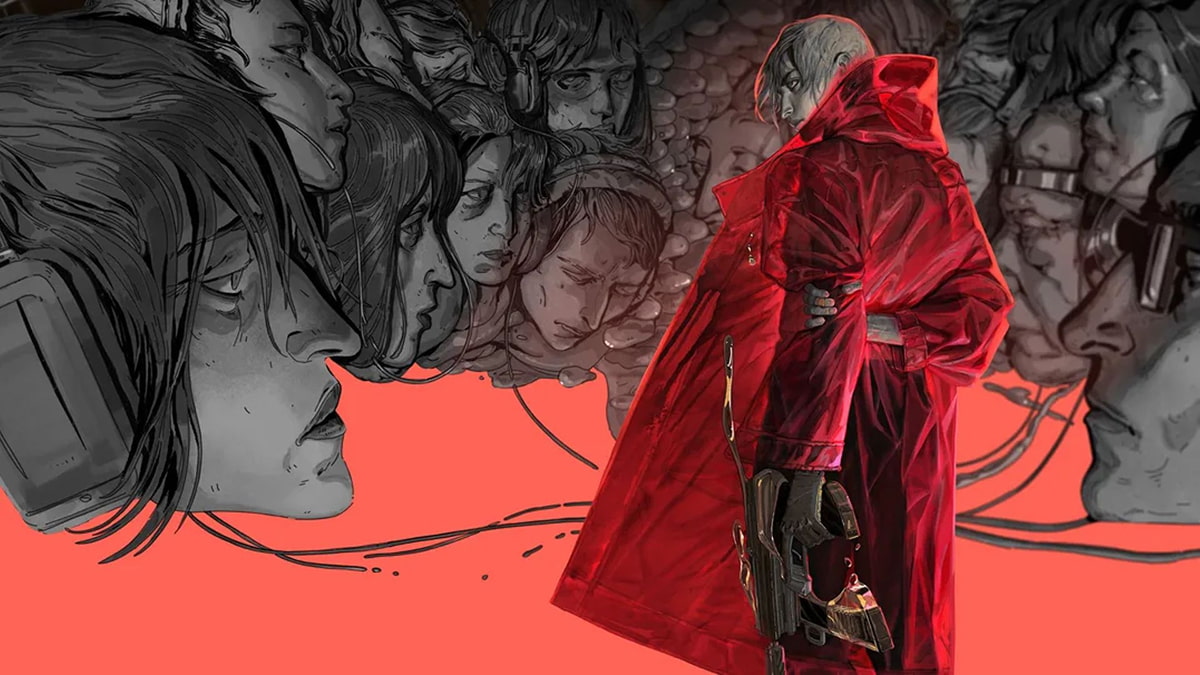

The art helps, too. The book has been put out by Rebellion Development’s literary arm, and that meant that all the game art could be done by actual game artists. Around 20 different artists put their names forwards, and in many cases were able to dial in on what the game was before he had written it up for the book. Crowley said working with Rebellion’s artists ‘really informed what I wrote in the description for the game as well. It was a real source of inspiration, quite often.

New fave. “Coleridge himself is completely beasted on opium and insists on a feud with Wordsworth” pic.twitter.com/Ug6VT61JsZ

— Alice Bell (@BabyGotBell) September 10, 2017

Though I have actually met Crowley in real life, almost all the interactions we’ve had have been through Twitter, and he uses it more creatively than most. He says he joined back in 2012, when it was ‘more of a vehicle for s***posting’, and while he doesn’t claim to be apolitical, he still enjoys using Twitter for what he describes as ‘weird microfiction’.

‘I think it’s good because, you know, in the same way as when I learnt journalistic writing I learnt economy of words, on Twitter you’re basically doing really short paragraphs. So you’ve got to have content and punchline in every single tweet.’

He also uses it for a kind of collaborative storytelling where, for example, he’ll experiment by dumping 12 consenting strangers into a group DM and telling them they’re in a pub in a version of Britain covered with swampland; he will have briefed certain members of the group beforehand to tell them that their secret objective is to get The Boys Are Back In Town by Thin Lizzy on the jukebox as often as possible, or that one of them is a mass of ants but the others can’t find out. At other times he has declared Twitter is a cop show for the following hour, and given other users the chance to be detectives, perps, or lawyers. I joined in on one occasion:

‘Oh yeah. Didn’t you turn into a cheetah?’

‘I think you said I was a cheetah.’

‘Oh yeah! Sorry, yeah, I did. Every police force needs a cheetah.’

‘I set off in hot pursuit and you just said I was a cheetah because I was the fastest on the force.’

/https://oimg.videogamer.com/images/817f/ac4ae409-8445-449e-8db5-835a61fa2895_jason_statham.jpg)

Big cats are one of the internal tropes of Crowley’s work — the nightmare that was Daniel Barker’s Birthday is referenced in the book as Leopard Exsanguination Tycoon, where you must sate Barker’s thirst for big cat blood. It’s been pointed out that there are a few subjects he seems repeatedly drawn to, and that crop up repeatedly in the book: pubs (he says that game characters are usually so competent that the idea of a game about staggering pissheads has an element of pathos to it); absurd dystopias like in Thomas the War Engine or Spice World: Legacy (something he’s only just becoming aware of, but puts down to enjoying things that baffle him to their wildest extremes); Phil Mitchell and Jason Statham.

There is, in fact, an apology to Jason Statham in the end word of the book, and Crowley said he’s slightly afraid that Statham might hear about or read some of the fake games that feature him. ‘There’s this sort of axis of cockney hard men, involving him and also Phil Mitchell,’ Crowley explained. ‘And there’s something of pathos to them because there’s as much bafflement as there is rage. I’ve got a slight fascination with that.’

The fascination with animals is easier to explain, because he just really likes them. Some of the proceeds of the book go towards ZSL’s amphibian conservation efforts. ‘We just got a new car and we chose it because it’s got one of those sunroofs that goes open the whole way, and we’re really near West Midlands Safari Park and it’s got giraffes, and if your sunroof goes all the way open the giraffes’ll get right in the car.’

After a pause, Crowley said, ‘We’re taking Daniel Barker actually. He’s coming up to visit. If he lunges for any of the big cats with a McDonald’s straw it’ll be time to worry.’

100 Best Video Games (That Never Existed) is out now.