Video Gamer is reader-supported. When you buy through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Prices subject to change. Learn more

The protagonist of Citizen Sleeper lives and works on a vast space station. Except they don’t. They are, in fact, elsewhere. Sleeping. A copy of their consciousness has been installed in a “frame”: a synthetic humanoid, composed of metal and wiring—and technically owned by a corporation—to whom people refer as a Sleeper. Thus, the title is at once a declaration and a sly probing of a dilemma: is our sleeper any less a citizen for the lack of an original body? Are we all not living on borrowed time, if not borrowed property? And how much of being a citizen really entails being awake?

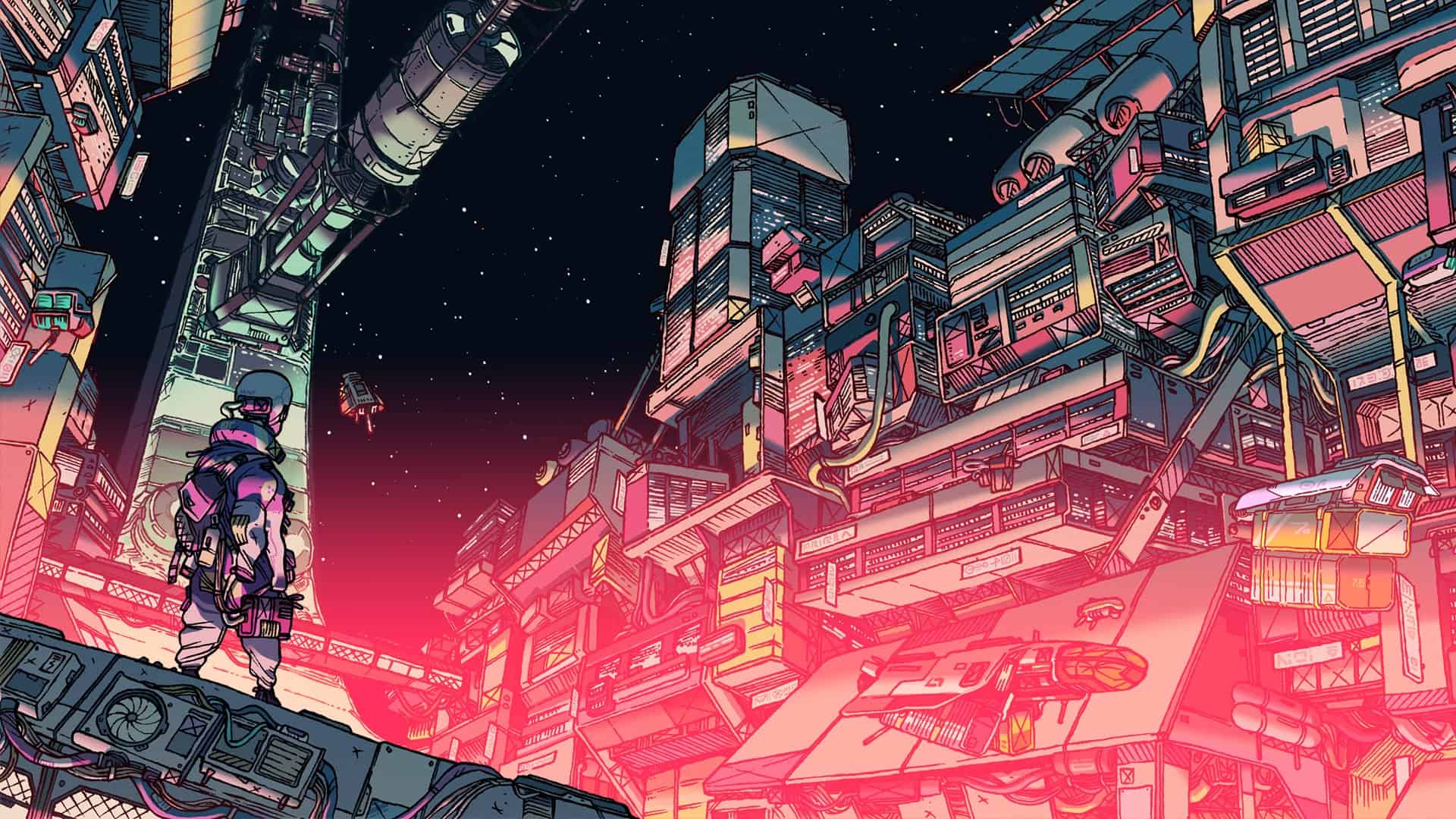

The station is named the Eye, and, though we do catch occasional violence on its streets, the place is hardly as bloodshot as Night City, from Cyberpunk 2077. Though it does possess a similar techno-bustle. Despite its name, it more closely resembles the wheel of a bicycle—circular, fitted with spokes, and thoroughly tired. The Eye is a ruin, tumbling from the hands of various companies and thence into disrepair. Those that dwell and thrive on its curvature do so in the knowledge that their days are precarious. Whether by mechanical or moral malfunction, it could all fall in a blink. You get the sense that life here has sprang up and spread amid the breakage of an old order, like moss furring the cracks of a derelict church. But the old order is still hanging around. A spectre is haunting the Eye—the spectre of capitalism.

If you have just assumed the brace position, fearing the brain-numbing turbulence of a lecture, I don’t blame you. There are characters, in Citizen Sleeper, that roll up and readily declaim their wisdom: “As far as I’m concerned, people should be the ones running the systems, not the other way around,” someone says. And at one point your character feels “A longing to be carried. Not by the systems that spin the suns, or the corporations that run the colonies. But by love.” Give me a break. But so, too, do we get Hardin, a grey-haired honcho with a criminal history, who offers a gruff rebuff: “It took work, diplomacy and strength to stop the Eye descending into chaos,” he says. “Not blind conviction or self-interest.” In moments like this, the approach of the game’s writer, Gareth Damian Martin (who is also credited as its creator and designer), takes on a more discursive air.

More than anything, Martin cares to give us texture. The drama and the action unfold in prose, and it’s the sort that prods at your senses more than your conscience. I particularly relished the funky strain of eco-fi that we get, as we glimpse a program “releasing its data like ink in water,” and as we watch an A.I. installing a fresh update, pressing it “down into the loam of data beneath them.” Who knew that the pleasures of programming are rooted in those of the green thumb, that information is there to be planted and pruned? Granted, we’ve all ventured onto Twitter and felt thoroughly soiled, but this is different. Martin has brought fecundity to software and, though some passages could do with a little weeding, the prevailing mood is both lush and lonely, like a walled garden.

Plus, if you like that, wait until you get to the food—to the oiled woks, the “thick chunks of marinated fungus,” the “sliced vegetables in some red-flecked dressing,” all of it “rich, spicy, delicately sweet.” When was the last time a game tempted you into ordering takeout? The one dishing up the feast is Emphis, a street vendor who could have stepped straight from the backgrounds of Blade Runner, with their steaming noodles and interminable rain. Emphis’s arms are ringed with curious scars, and, in one scene, we trace them to a dark backstory. Emphis, we are told, was once grafted onto a machine, called a “Bonesuit,” (shades of the Skull Suit, from Metal Gear Solid 2: Sons of Liberty) for the purposes of robo-boosted labour; but it’s the artwork, by Guillaume Singelin, that does the heavy lifting here. Emphis is laughably saddled with equipment—pans, bottles, bags filled with utensils, plastic trays bearing mushrooms. He is the spit of Norman Reedus, in Death Stranding, Hideo Kojima’s study of baggage-loaded bodies. Singelin’s style is akin to that of Yoji Shinkawa—who partnered with Kojima for that game, and many others—albeit more cleanly drawn, and clouded with the dreamy hues of Jean Giraud.

Along with Emphis, we also get Riko, a kindly old woman with a crutch, who dwells in the Greenway, a verdant belt from whence the station, presumably, draws its oxygen. There she plies her botanical skills, breeding and brewing all manner of concoction, and runs the Hypha commune, where the hippies go, rent-free, to focus on their personal growth. Then we have Tala, who works at the Overlook bar, an unstilled soul who yearns to raise her spirits by making whiskey, and rebranding the establishment. And Bliss, a mechanic who floats and tinkers in zero gravity, itching to be cut adrift from the Eye. What Martin is doing, in short, is assembling the seethers: those ground-level extras that throng the cyberpunk genre, usually lending assistance to a Harrison Ford-like hunk.

As if to drive the point home, along comes Ethan, a bounty hunter with a shoulder holster, a shock of blonde hair, and a mud-brown jacket. Naturally, he is (1) handsome, (2) a bastard, and (3) after you—or, at least, after the money that he will net for your body, the better to glug himself into a stupor. He is, in other words, a reshuffled and half-cut Deckard, and a stark reminder that, of all the characters here, none would be more secondary, in a traditional tale, than you. And even here you are hardly a hero. True, you get to make choices; key decisions and dialogue options are there for the clicking, but the success of most of your actions is carried not by the systems that spin the suns, nor by the corporations that run the colonies, and still less by love, but by that most loaded of cosmic forces: luck.

Each day—or “cycle,” as they are called—you are dealt six dice. These are fed into various activities; everything from sawing through weary hulls in a salvage yard to playing a game of tavla (a kind of backgammon analogue) is governed by whichever die you press into a slot. Jewel it with a six, and you are likely to reap bountiful rewards; jab a one or a two into the effort, and you may lose or, worse, come away with your energy sapped. This is replenished, easily enough, with food, but your Sleeper suffers a deeper malady. Essen-Arp, the corporation that considers you little more than missing equipment, has bestowed on you a “planned obsolescence”—an insurance policy of sorts, which turns your firmware friable. Consequently, you require regular doses of stabilising medicine, which don’t come cheap. As we are informed by Sabine, a doctor who sports a poncho of translucent-yellow plastic, as though shielded from an ever-present downpour, “Nothing comes free Sleeper, remember that.”

Indeed, and not the least surprising thing about Citizen Sleeper is that its sights and smells do not arrive at the cost of fun. The patterns of its play—doing jobs for cash, helping others, completing quests—have the rhythm of work, but they are delivered, via a string of computerish interfaces, with beeping abstraction. Your toils are not your own. A few years back, I spoke to Martin, who said, “We are used to being the ‘body’ in a game—the one who opens doors, fights enemies, physically explores spaces. . . . I needed to find a different language to the typical direct avatar control and physical interactions of a game. That was when I turned to the idea of a computer interface.”

The subject of our conversation was Martin’s debut, In Other Waters, a game set in an alien ocean, of which we never see a drop. We assume the role of an A.I., plugged into the diving suit of a xenobiologist, and we see the world through the swish and swirl of its emanations. “To me there’s something wonderful about the abstraction that is possible with interfaces,” said Martin, “the way they can represent worlds through data, signals, and systems.” Much of the power of Citizen Sleeper flows from that game’s singular premise. Both share a composer, in Amos Roddy, whose score is rich in susurrations and synth. And both ache with the drive to escape. Hence the hacking ability that your Sleeper discovers, which casts the station in a snowy haze; this ghost world, we are told, curls through the physical realm “like smoke through air.” When, later on, one quest offers the chance to leave your frame behind and slip permanently into this formless plane, it’s a moment of breathless possibility; but you can’t help wondering from what personal depths such passages must have emerged. Machines, bodies, people, interfaces, souls: with Citizen Sleeper, Martin’s elusive themes pass—like ink in water, like smoke through air—into the perfect frame, and reach a thrilling consummation. But nothing comes free.