You can trust VideoGamer. Our team of gaming experts spend hours testing and reviewing the latest games, to ensure you're reading the most comprehensive guide possible. Rest assured, all imagery and advice is unique and original. Check out how we test and review games here

There are few sentences that send me running for the nearest window, gasping for fresh gravity, as potently as, “I had the strangest dream last night…” Most dreams, possessing the narrative cohesion of soup, don’t lend themselves to the telling without excessive use of the words “and then,” generally combined with “for some reason.” And why bother stressing how strange it was? If dreams are the irradiated run-off of our daily grind, the hissing steam of our subconscious, then why the hell shouldn’t they be strange? Worst of all is that, even if the ensuing recount has you gripped, it’s guaranteed to come to nothing—worse than nothing, it arrives ready-spoiled by the dispiriting promise of “and then I woke up,” at which point you will wish they hadn’t bothered.

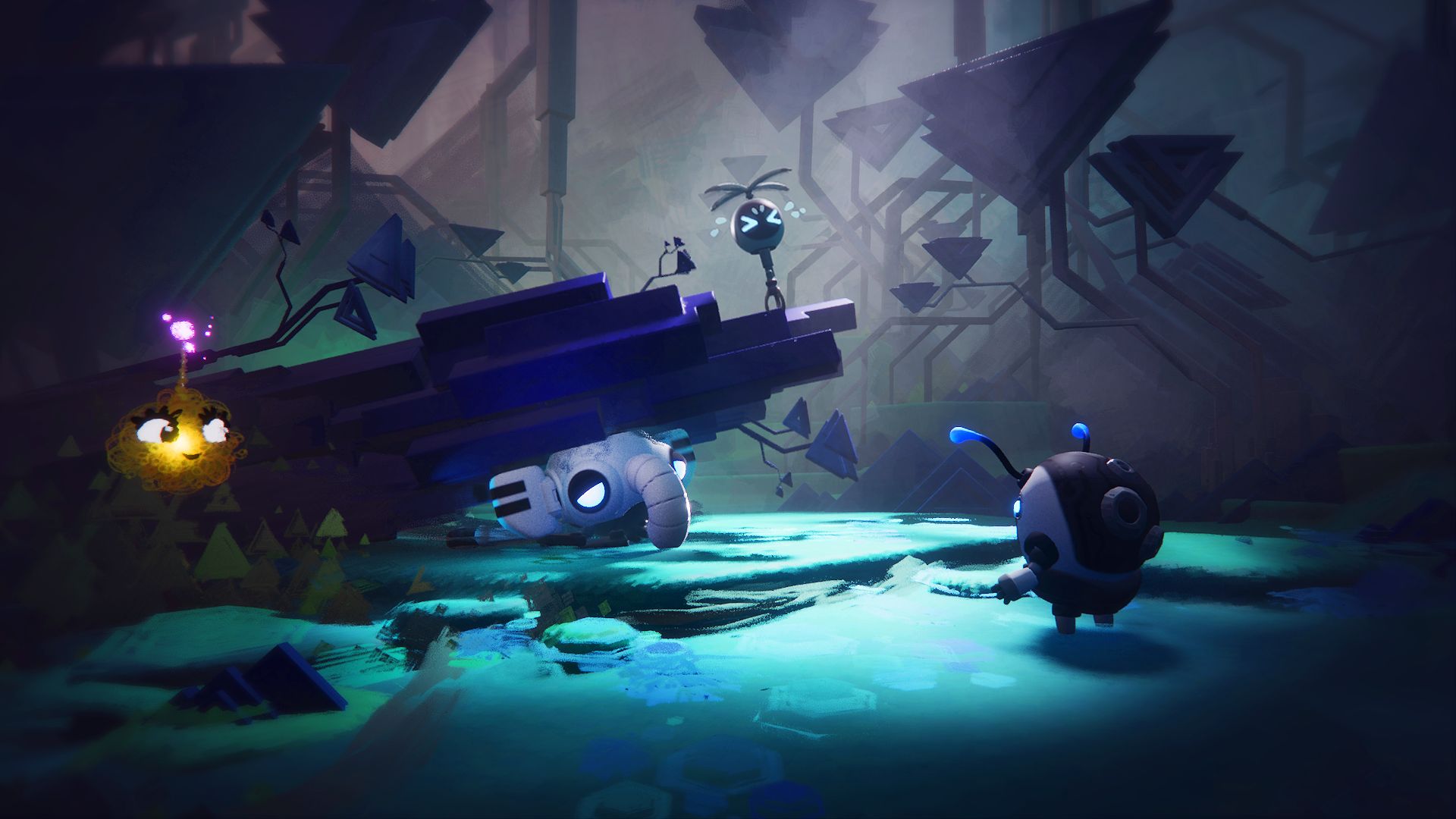

Enter Guildford-based developer Media Molecule, whose newest game, Dreams, isn’t exactly new, nor is it wholly a game. It entered development in 2011 and early access last April, and, despite the fact that it has a campaign—“an interactive, movie-length musical story” called Art’s Dream—the bulk of its buzz is the ability to make your own games (or indeed Dreams, as they are designated), without using a single line of code, using the suite of creative tools that Media Molecule has provided. The question is: Will Dreams make Dreams that are worth sharing, or will it, as is normally the case, merely indulge the sharer? After a number of days spent both “Dream Surfing” and “Dream Shaping,” I can confirm, by way of copping out, that the answer is: both.

Starting with Art’s Dream—which, we are told, “was made entirely in Dreams, to give just a glimpse of what’s possible with our tools”—I began to wonder if what was possible with these tools was only glimpses. The plot is wrapped around Art, a double bass player who has recently quit his band, obeying the raging rhythm of his own ego, after being told to “tone it down.” He embarks on a quest to rediscover the musical merits of modesty and, along the way, is plunged into a hodgepodge of play and visual styles. Kareem Ettouney is credited with leading the game’s art direction, to which my question would be, Which one? It seems to fly in all directions, as befits the lure of a blank, all-encompassing canvas.

Art’s Dream begins with an enticing noirish flavour. The characters are long-limbed, dark, and crooked. They have rocky faces, as though they were chiselled from cliffs of colour, and you start to settle into Art’s interior world—one in which the paving stones and steel pillars of a train platform peel happily away and whirl into the sky beyond, and in which the bright billboards outside a jazz club blur in the rain to form a copper fog. But then you’re whisked to toytown, by way of a childhood memory, and play as a metal robot, wheeling along paths of electric light. Or you find yourself taking the form of a teddy bear, swinging a mallet through pastoral platforming stages. Such flights are fine for an actual dream, in which any notions of jarring geography are dismissed with a flippant wave of the frontal lobes. While playing through Art’s Dream, however, I couldn’t help bristling at the clash and wishing they would tone it down.

The advantage of a game like Dreams, of course, is that the toning—along with the texturing, colouring, sculpting, and the general creative juicing—is up to you. Every effort is made to minimise the daunting fear of being faced with a void where a vision of beauty should be. For a start, you can take any Dream you find and “remix it,” putting your own spin, small or large, on a pre-existing clump of polygons to glean fresh inspiration. (Hunter S. Thompson, wanting to get a feel for genius, had a similar idea; word has it he would type out pages of The Great Gatsby, huffing the fumes of Fitzgerald’s prowess.) You also have a raft of tutorials at your disposal, rising from beginner, through intermediate, to advanced-level classes on just about everything. The detail can be dizzying; when one tutor informed me that “there’s a whole tutorial on selecting and grouping objects,” I couldn’t help but detect a vague air of threat.

Heading into the Dream Workshop, wherein you aren’t so much shown the ropes as made gently, painstakingly aware of their constituent fibres, you could be forgiven for tenderly placing the DualShock 4 on the sofa and retreating to your bed. The game’s narrator, the Dream Queen, provides you with words of doubt-busting encouragement—though, it must be said, she has the definite zest of the overzealous. At one point, she says, “This composition is so wonderful it defies description!” It was a cupcake perched on a glass pyramid. Stick with it, though, and you will be rewarded with the feeling of fluency in something that sidles close—with its shortcuts and shifting logic—to a new language. The process is made possible by the motion sensor of the PlayStation controller, which is repurposed as a sort of aerial mouse—you can also, if you’d rather release your inner wizard, opt for the PlayStation Move controller and waft your creations to life as if with a wand.

There’s something to be said for an exclusive game that isn’t just not on other consoles but actually couldn’t be. Dreams is exactly the sort of nebulous, description-dodging thing that Sony’s marketing department, with its deep pockets and pretentious spirit, would relish making oblique reference to in a bewildering ad campaign. But it could also have come from no other developer. Media Molecule’s back catalogue is thronged with such genial games as LittleBigPlanet and Tearaway, both of which have the frolicsome, lick-and-stick feel of children’s arts and crafts. It goes without saying that such carefree airs can only be achieved with an ocean of effort, an office crammed with talent, and an array of precise tools. Which makes it all the more laudable that Media Molecule, ever since it began, in 2006, has enjoyed nothing more than offering up the building blocks of its worlds to players, kindling our imaginations like an encouraging parent. Dreams goes further, in its efforts to beckon us through the creative curtain, than any of the studio’s previous games; it’s the scratching of a founding itch.

You may be as surprised as I was to find yourself snapping out of a tunnel-visioned trance—spent cloning blocks of earth and blurring them into a mountain range, for example, or massaging a ribbon of grey into a constant billow and thus conjuring satisfactory chimney smoke—and think, Where were these obsessions last week? Have they been planted or dug up? The true value of Dreams, I suspect, will drift into view gradually, as our gaze is drawn to other games. It was only as I was playing The Last of Us Remastered, a couple of days ago, that I noticed a bundle of new wiring in my brain; standing next to a thrashing river, I saw that its currents were blasting the beach at an odd angle, and I wished for nothing more than to click on the comb tool, pull the shoulder button, and brush it back on course. Perhaps what Media Molecule has done is best thought of as video game Freud: getting us to grips with the machinery churning below the surface of our awareness by having us think about our Dreams.

If all this sounds rather solitary and obsessive, I recommend a trip to the Dreamiverse, wherein you peruse the efforts of your fellow-players—be they bursts of animation, music, or games small and sprawling—to get a feel for the community, which is where both the possibilities and the legacy of Dreams will be shaped. If you would like to set up a lengthy meeting between your jaw and the floor, then check out Fallout 4: Dreams Edition (WIP), by Robo_Killer_v2, which includes trackable quests, weapons, a sufficiently parched wasteland, and a Pip-Boy. Horror junkies will be pleased to see that nightmares are just as well represented. There is P.T. (1.04), by lewisc729, a fastidious recreation of Kojima’s short-lived teaser that doesn’t skimp on the shocks, and The Ornithologist’s Private Collection, by mattizzle1, which has more terror in its title than most horror games can muster.

“What is common in all these dreams is obvious. They completely satisfy wishes excited during the day which remain unrealised.” Those words are from The Interpretation of Dreams, and I think that, for the most part, Freud is right—although, in the case of Wario crashes into a nuclear plant and dies., a short film by brutalvix, that may not reflect well on the health of us. Still, Dreams is devoted to the realisation of exciting wishes, and with it Media Molecule has its defining, if not quite definable, game. The limits of its possibilities will become clear only as they are pushed back. “To the dream ‘No’ does not seem to exist,” said Freud. We shall see.

Developer: Media Molecule

Publisher: Sony

Available on: PlayStation 4

Release Date: February 14, 2020

To check what a review score means from us, click here.