You can trust VideoGamer. Our team of gaming experts spend hours testing and reviewing the latest games, to ensure you're reading the most comprehensive guide possible. Rest assured, all imagery and advice is unique and original. Check out how we test and review games here

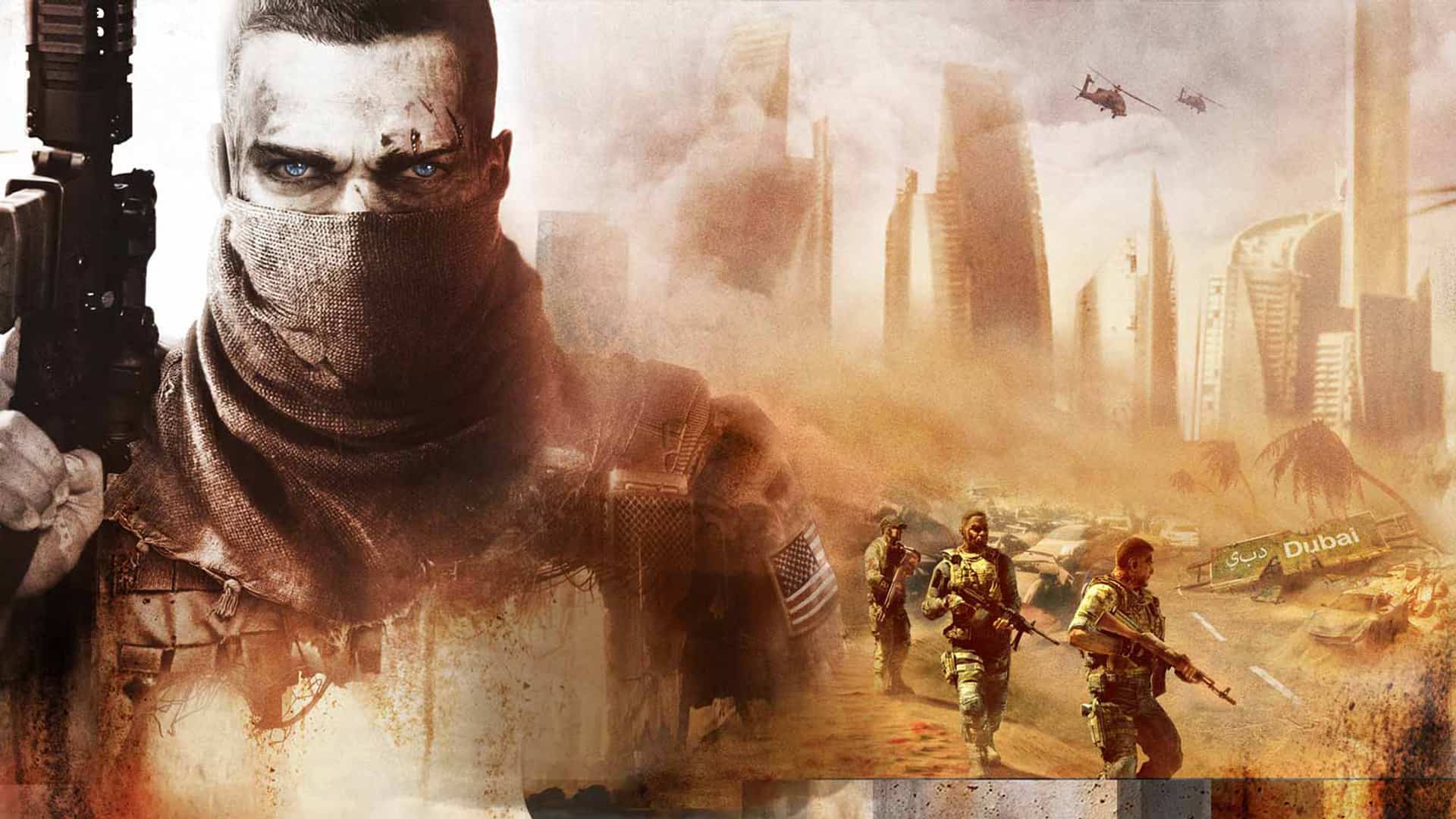

Third-person shooter Spec Ops: The Line hits stores on June 29. We chatted to Shawn Frison, Senior Designer at Yager to get the inside word on gameplay mechanics and the game engine.

You’re using Unreal Engine 3 – have you modified it to deliver the visuals you wanted for Spec Ops the Line?

Definitely. We’ve been tinkering with this thing for a few years now, and there aren’t too many corners we haven’t touched. We’ve done everything from improving the visuals to adapting the AI and weapon systems to implementing all the pieces we need for our sand systems. Unreal is an awesome piece of technology, but I think we really made it our own.

How does sand play a part in the gameplay? Can you give a few examples of the scenarios players will experience.

Basically, we wanted sand to be this constant presence without getting to the point where it turns into a gimmick. In terms of gameplay, we do a few different things with it:

Grenades: Any time a grenade lands in the sand, it behaves a bit differently. In addition to the normal explosion it creates, it also kicks up a cloud of sand that blinds and stuns enemies to give you a brief tactical advantage.

Sand Avalanches: Throughout the game, the player will have the opportunity to unleash mountains of sand on enemies by shooting out glass or destroying supports.

Sand Falls: Occasionally, you’ll see sand trickling from a vent or similar object in the ceiling. In these cases, you can shoot at the vent to let loose sand to stun enemies.

Sandstorms: When sandstorms sweep through, the whole dynamic of combat changes. Aiming is more difficult, visibility is reduced, you can’t tell where grenades will land, you can’t communicate with your squad – it really shakes things up and adds a lot of tension and uncertainty to combat.

And, of course, we use it a lot in various scripted ways to add variety and showcase some big, impactful scenes. For instance, in some of the footage we’ve released you can see a scene where the player thinks he’s walking on solid ground, but it turns out that there’s a skylight underneath the sand. After an RPG explodes nearby, the ground completely collapses beneath him. The player falls down, barely catches himself with one hand, and has to fight off enemies by firing with one hand while he’s hanging there. We try to have a lot of dynamic moments like that to keep players on their toes.

Audio is a major part of creating a believable game world. What have you done to make Spec Ops The Line excel in this area?

First, we did a ton of research. We spent a lot of time listening to how different weapons sounded, for instance, as well as playing a lot of other games to see which types of treatments were most effective.

Another huge factor was just iterating until we were happy. For instance, our current audio mixing took a very long time to settle on. It’s incredibly difficult to find that balance between making sure that your explosions and weapon sounds and so forth are loud and impactful, but don’t completely drown out the narrative that was so important to us. We spent a lot of time tweaking and re-tweaking to get this right.

Voices in general were a big deal, actually. In addition to spending a lot of time getting our script and recordings just right, we also put in a few tricks that I think help make us stand out. For instance, as in a lot of games, the characters respond to events with voice systemically. For instance, if someone throws a grenade or kills an enemy or reloads or spots an enemy with an RPG, the system will automatically play a line. That’s standard. What we do is new is to make these lines change throughout the game as the squad is affected by the situation. For instance, in the beginning of the game they might calmly report, “Tango with an RPG en route.” Later on, it might devolve into a panicked shout of, “F***, RPG! Get your goddamn head down!”

Finally, music was very important to us. We attacked this from two angles: first, we hired a composer who crafted a really unique score that gives our game a pretty cool, unearthly feel. And second, we have a lot of licensed music that we play in the actual game world from speakers that help define the Radioman character, as well as adding another very strange, surreal element. You wouldn’t typically expect classic rock to be playing over a scene of horrible carnage, but those are exactly the kinds of moments we wanted people to experience.

How do your squad members help out in battle? Is it essential to use them or can you go lonewolf?

We wanted players to value them a lot without making them require a ton of management. To that end, we set them up to behave pretty intelligently and be effective in combat even if you don’t actively use them. You can really see this in the scenes where you get separated from the squad, and suddenly you realize how much harder it is to deal with everything on your own.

On top of that, we have an easy to use, contextual command system if you want to use them to target specific enemies. When you use this, they’ll react in ways that are appropriate – sniping a long range enemy or using a grenade on a guy hiding behind a turret, for instance.

The main thing is that they are professionals, they know what to do, and if you don’t want to direct them they will behave like pros. By the same logic, if you are cornered or pinned down in a specific location, you can expect your squad to realize that and they will offer to help by throwing a stun grenade into the enemy ranks with a simple button press.

So the short answer is that we wanted the squad to feel as easy and natural to use as possible, but we support both play styles.

Moral choices appear to play a big part throughout the story. How do these affect the gameplay experience?

It depends on the choice, and unfortunately I can’t say much more than that without spoiling things. Our main goal was to make it so that the choices themselves are impactful – so that the struggle to decide and do the right thing genuinely matters in and of itself. We did a lot of research, talking to our military advisor and looking at testimonies from soldiers in the field, and the key point we took away from this is that these decisions are not really about right versus wrong – they’re about picking the least-terrible of two bad options. We wanted to put players into that gray moral area where you’re not quite sure what the right thing to do is, even after you’ve made the decision. Incidentally, that’s where our title comes from: there’s a blurry line between what’s right and what’s necessary, between duty and morality, between reason and madness… that was the area we wanted to explore.

Spec Ops: The Line

- Platform(s): PC, PlayStation 3, Xbox 360, Xbox One

- Genre(s): Action, Shooter, Third Person

/https://oimg.videogamer.com/images/fd8a/spec_ops_the_line_14.jpg)