Video Gamer is reader-supported. When you buy through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Prices subject to change. Learn more

The ‘adventure’ in the title of Zelda II: The Adventure of Link should be changed to ‘tragedy,’ so cursed is the game’s hero. It isn’t the usual sorcery and scheming of the demon pig Ganon or any of that swill that’s doomed the kid; it’s time, and being ahead of it. He must get irritated by that twerp with the ocarina getting all the glory – and envious of the power to hop ahead into the future, where he would have been more warmly received.

‘Black sheep!’ the naysayers bleated in 1987, but next week the game will be available via Switch Online, 32 years after its original release, and it’s ripe for reappraisal. If you find yourself unable to admire Zelda II, then you must at least admire Nintendo's bravery in blowing up such a successful formula. What was once top-down was suddenly side-scrolling; a once bone dry world, with a sky the glow of heated metal, was now blue and lush and strewn with bustling hamlets.

How strange that something now so inseparable from the fabric of a Zelda game – the village hub – seemed so out of joint for people back then. It almost appeared as if the game’s code couldn’t cope with their presence: one citizen of the town of Ruto famously declared ‘I am error,’ evidently insecure about his place in the world. But he needn’t be; the towns in Zelda II leant it a lived-in feeling, with cavernous houses to poke around in and NPCs scooting about the streets. It was nice to see what was worth saving; after being worn down by obtuse puzzles, I was willing to let Ganon get his trotters on the original game’s doomy burg.

Not that Zelda II doesn’t have its share of block-headed puzzle design. But its challenges were evidently engineered with less of an insistence that players purchase their eureka moments with Nintendo Power magazine. For one thing, the world is laid out linearly, with a beaten path to bear you in the right direction. And for another, townsfolk offer clues, they heal you, and then offer worldly advice like ‘If all else fails use fire’ – which, while not so useful in-game, has come in handy in real life for things like spiders and overdraft statements.

In fact, there’s something of the bank ledger to Zelda II, a strange mustiness that’s lingered through the years. If you’re anything like me, it’s a pain to see a grassy playpen fenced in with numbers – XP rising from felled monsters like pollution, ticking upwards to mark your surging power level, and trammelling your use of magic. It would be thirty years until numbers reared their head again, in Breath of the Wild – with its clothing and weapon attack stats, durability ratings, and food health numbers – and they were warmly embraced. Alas, fashion is fickle.

But there is magic in Zelda II, buckets of the stuff: life spells, shield spells, thunder spells, and, in what became something of a series flourish, the transformation spell. The giddy glee I feel at the sight of Link bobbing above the heads of his foes, in fairy form, is of a kind that wouldn't come again until Castlevania: Symphony of the Night let me become a bat, ten years later. And none of the transformations that followed in the Zelda series – be they bunny, wolf, or, Octorok – were as puckish or liberating as that one.

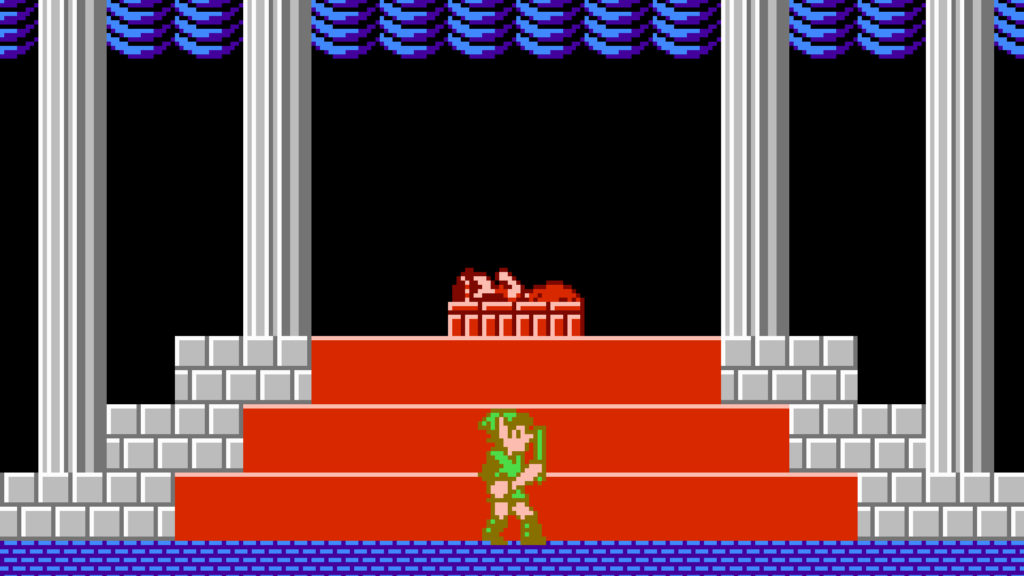

Which isn’t to suggest that the Link of Zelda II was a shirker of confrontation, far from it. The change that lunges out and pokes you on the nose the fastest is the side-on camera, which gives us a full-bodied view of its close combat. Look at Link’s stance after he fires a magic bolt, the whippy recoil twanging his arm back like elastic, as if each blast tires arm. So much atomised drama in a single frame of animation.

Each fight was bound by the feeling of mortal weight, as well. Not just to avoid the game over screen – a dread concoction of Ganon’s piggly silhouette against a backdrop the colour of dried blood – but to ensure you were present in the moment of each bout. You could block and strike high and low, and jump strike; speaking to the masters scattered across the land yielded further techniques, like the upstab and downstab. (The latter is my go-to while playing as Link in Super Smash Bros.). That sort of clashing complexity wouldn’t return until the series went 3D and took up line dancing as a form of evasion.

It was put to no better use than the game’s final boss fight, which saw you face off against Link’s Shadow – long before it became such a worn-soled cliché. In a sublime touch, he wouldn’t attack if you didn’t, and the fight took on the feel of the mirror scene in the Marx brothers’ Duck Soup, only with a current of bitter blackness. It’s the enduring image I have of Zelda II – a game that struggled with the expectations placed upon it by its predecessor. A brave and ingenious hero, battling a shadow of his own casting.