Video Gamer is reader-supported. When you buy through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Prices subject to change. Learn more

All video games have a story. The first Donkey Kong is about a small man in overalls trying to rescue a woman from a large and angry ape. Doom is about a hench marine fighting demons (Doom has four novel adaptations, by the way). All video games have a story, just not necessarily a very complex one. Where the Water Tastes Like Wine is very interesting because it’s a game where the story is about telling stories, which then makes you wonder about all the video games that aren’t explicitly about telling stories.

In RPGs, for example, there are often instances where you can undertake a quest for someone (‘Find my missing brother’) and then have a choice about what to say to that someone when you’ve completed it (‘I’m sorry, but he’s dead. His body was just lying in the forest and has been partially eaten by whatever fantastical variant of wolves live in this world. Here is the ring you gave him, which holds immense sentimental value for you.’ vs. ‘I couldn’t find him, and furthermore definitely did not loot his body of literally everything, including a cheap ring.’), which means you’re telling a very small story within a story. In fact, developers like BioWare or Telltale Games have made it a USP that all your own particular choices across different episodes or chapters or even entire games that come out years apart will add up and create an experience unique (to within several programmable degrees of ‘unique’) to your personal version of the protagonist.

Sometimes the game has enough gaps that you can fill them in yourself. A lot of the time, because the game is busy trying to fit in a lot of other stuff like shooting exotic aliens and having sex with exotic aliens, the story is told in bits and pieces that you put together –suspiciously half-burnt diaries, unsent letters, voice memos recorded just before the enemies broke down the door, adverts for soap that manage to reference the terrible authoritarian government said soap is slung under, and, very occasionally, actual dialogue. This means that if you miss one or some of the fragments you can experience a very different story to the one that the developer had in mind themselves, as if they were yelling improv prompts that you then worked from independently (incidentally, Professor Paul Fletcher of Cambridge University, who consulted on Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice, said he’d ‘long had a belief that video games are an incredible forum in which to explore how we come to terms with reality, because you’re placed in this setting about which you know very little, and you have to explore it and probe it and somehow assemble the pieces in order to solve the game,’ which is similar to how our brains must interpret everything outside the bone box they’re shut in into something that makes some kind of sense).

Because nothing is new, neither is this. There are many board games that call on the players to collaboratively weave a story based on prompts, including a single player card game that leads the player through having a prolonged sexual relationship with an actual monster. At Christmas you might have played that parlour game where you draw part of an animal, fold the paper down, and pass it along for your aunt to draw the next bit; there’s a variant where you write a story sentence by sentence. At the end you unfold the paper to reveal the terrible creation you all wrought together. And tabletop roleplaying games are notionally written by the GM but go so wildly and at-the-slightest-touchedly off-piste due to the players being quite stupid, so it ends up as a story that you all told together with a bit of help, which is nice.

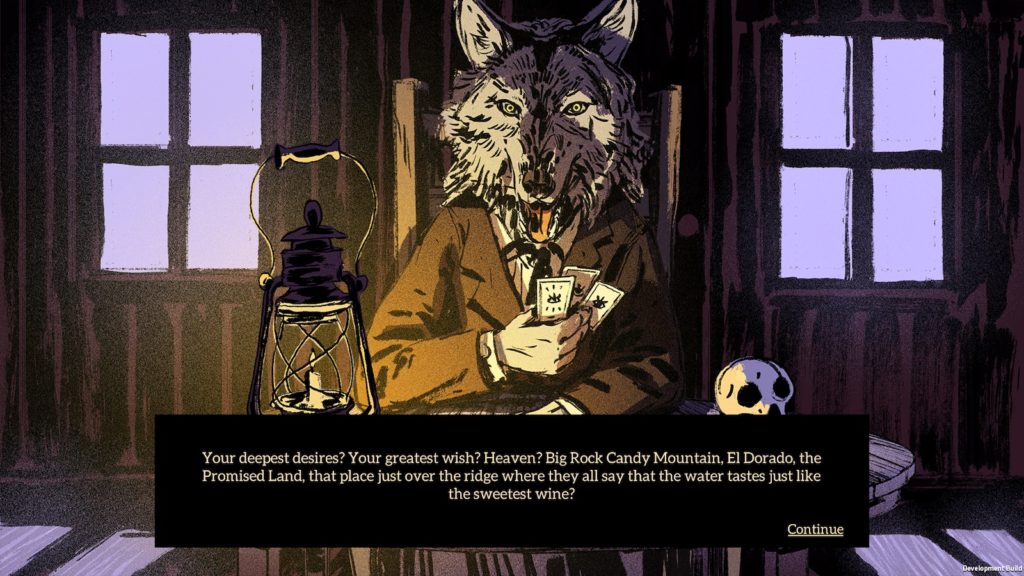

In Where the Water Tastes Like Wine a man with the head of a wolf and the voice of a Sting sets you, a skellington with a bindle, on a journey around the USA circa the Great Depression, with the aim being that you collect and share stories – true stories – as you go. You meet other travellers, displaced by the different forces rocking the States, who you tell your stories to, and then they tell them on again and sometimes you get told one of your own back to you, but it’s bigger, different, stranger, better. The other travellers in the game were all written by different people too, so it’s a collaborative story about collaborative storytelling, as is watching mundane happenings grow into myths. Do I, you think, feature in a story that someone else has told? How do I look in that story? Would I recognise me? Probably not. People make stories their own in the telling, and you can do that with games too.

Her Story

/https://oimg.videogamer.com/images/b7b5/her_story_14.jpg)

Her Story came out in 2015 and is proof positive that all FMV games ever are amazing. You take on the role of a police officer trawling through the archive footage of a woman who was interviewed seven different times after her husband’s death in 1994. The system is antiquated so you must search for video clips by keyword only, rather than being able to watch all of them in full, in chronological order. The amount of footage you uncover from each video will colour your view of the entire case, so you will quite possibly have an entirely different opinion on what happened compared to your friend, who searched for slightly different words than you did. It’s very, very good and a bit unsettling, especially if you find the clips where she’s singing. Her story changes across different interviews and you’ll find you have, almost without thinking, filled a notepad with words you searched, words you searched that turned up something useful, and words to search based on what you found. And your pad won’t look like anyone else’s.

Dear Esther

/https://oimg.videogamer.com/images/70d0/dear_esther.jpg)

Dear Esther is probably the first ever game in the walking simulator/first person experience/just f***ing leave it alone genre, first released as a Source mod in 2008 before getting a commercial release in 2012. Exploring a barren, blasted island, reaching key locations triggers music and a piece of narration, but the narration will be different each time, with allusions to a car crash, illness, seatbelts, other men who have lived on the island and apocryphal discoveries they’ve made, and different legends about the place and its history. Each playthrough will throw up different sections and in a different order, so whether or not you find the story compelling it means you’re able to treat each play through as a different, albeit similar, tale entirely, not the same one told in a new way, which is a very cool thing.

Journey

/https://oimg.videogamer.com/images/ce08/journey_10-139079.jpg)

Every time you finish Journey you end up back at the start again. It’s beautiful and calming, and along the way you meet up with other players. Sometimes you’ll be with the same player the whole way through, and sometimes you’ll play with many different ones in succession, surfing over sand and through ruins to make your way to a mountain. And it doesn’t matter what languages you speak because your avatars communicate by singing to one another at the press of a button. Along the way you uncover murals that tell bits and pieces of the rise and fall of a civilisation but nothing is explicitly spelled out. The journey the character goes on is difficult and sometimes dangerous, but you don’t have to do it alone, so you create every journey with someone else.

Shadow of the Colossus

There are many, many examinations of the morality of Shadow of the Colossus. It got a remake/remaster (nobody seems entirely sure) this year, and has all the hallmarks of a Team Ico game i.e. extremely giant creatures to climb up and a terrible camera. As Wander you are tasked with slaying 16 Colossuses that are… really big… in order to resurrect a dead girl whose relationship to you is left unclear. The giant creatures are strange and a bit alien, but given enough character and recognisable features that you can imagine they have big, slow internal lives of their own, and that there’s really no need to rock up and stab them repeatedly in the head. But you keep doing it. When we played it on a livestream we mostly bonded with our horse, who we insisted was named Brian despite the game trying to tell us something contrary.

Literally any game ever, it doesn’t matter, and nobody can own what you do with the inside of your head

/https://oimg.videogamer.com/images/f14d/de363bd7-0a99-4ace-978b-d8611b5f39df_DQbZgHLVAAEjtaa.jpg)

The possibilities are both endless and very silly! Make it your own in the telling.