You can trust VideoGamer. Our team of gaming experts spend hours testing and reviewing the latest games, to ensure you're reading the most comprehensive guide possible. Rest assured, all imagery and advice is unique and original. Check out how we test and review games here

Well, it’s not been a banner year for games, as 2017 was, but the likes of this list would stand tall alongside any vintage. I was cruelly only allowed five, and the games that were left off break my heart. Nonetheless, what’s here has made me happy – deliriously so, at times – and made me think. You can’t ask for much more than that. Here are five of the games that I adored this year, in no particular order.

Forza Horizon 4

Games give us the power to wire our childish drives into welcoming ports and see them reimagined. Just as we played with toy soldiers, we were given Gears of War; as we pushed and tinkered with toy cars, we are treated to Forza Horizon 4. It’s as if developer Playground Games went to work with two tools: a bucket of paint and a brush, the better to fix a bright go faster stripe to the formula of Forza Motorsport.

Some things simply mustn’t be overthought. Driving at irresponsible speed is ecstacy, and here it’s treated, rightfully, as an art. The husbandry lavished on vehicles of all breed and hue is dazzling, and the rush of racing them – difficulty and realism lacquered with forgiveness – is sublime. My time with Forza Horizon 4 has induced some of the goofiest blissed-out grins of the year. The quality that glistens brightest, like a rainbow in an oil slick, is generosity.

A crush of cars has your garage bursting at the seams, with new models dropped in your lap like toys after each event. Each event, meanwhile, offers a fresh test chamber with which to bend and wring every drop of joy from your driving. Most generous of all is the game’s burnished Britain: a playpen of country roads that weave round dewy dales, crumbling away to wet dunes and paved streets. Besides, I can’t recall the last game to let me drive a 1986 Aston Martin V8 Vantage, just as Timothy Dalton did in The Living Daylights. If it only offered that, it might still have made the list.

Return of the Obra Dinn

With Papers, Please, Lucas Pope demonstrated the devastation that could be wrought with stationary. Paperclips, stamps, and signatures were all vested with the power to vouchsafe freedom and happiness, and to destroy – to score a line through a life by following the rubric of a bureaucracy. Now, with Return of the Obra Dinn, he turns the tables; bureaucracy and stationary are employed to make sense of devastation.

The Obra Dinn, a merchant ship, has returned to port after being lost at sea for four years. Everyone who was on board is either dead or missing. It falls to you to carry out an insurance audit by means of magic; your pocket watch is imbued, by what office we aren’t told, with the power to see the last moments of each life in still tableaux – part drypoint etching, part dot matrix. You then collate the chaos, with the help of a manifest and a map. As each name is inscribed with the relevant fate, you’re met with a triumphant tremor of strings, as if order has been restored with the power of paper and ink.

Of course, it hasn’t, and Pope trades, once again, in irony. He speaks to the impossible task of creating sense and story from the chaos of life, like sifting through silt. Return of the Obra Dinn is that rarest of things: something new. you'd expect intrigue and chills from a ghost ship, but, with sparse ingredients, Pope has sketched in some drama and sadness as well. His graphical style, a dither of grayscale and the faint suggestion of green, made me feel like a bat, as though the world were revealed through echolocation – only, the echoes were long gone.

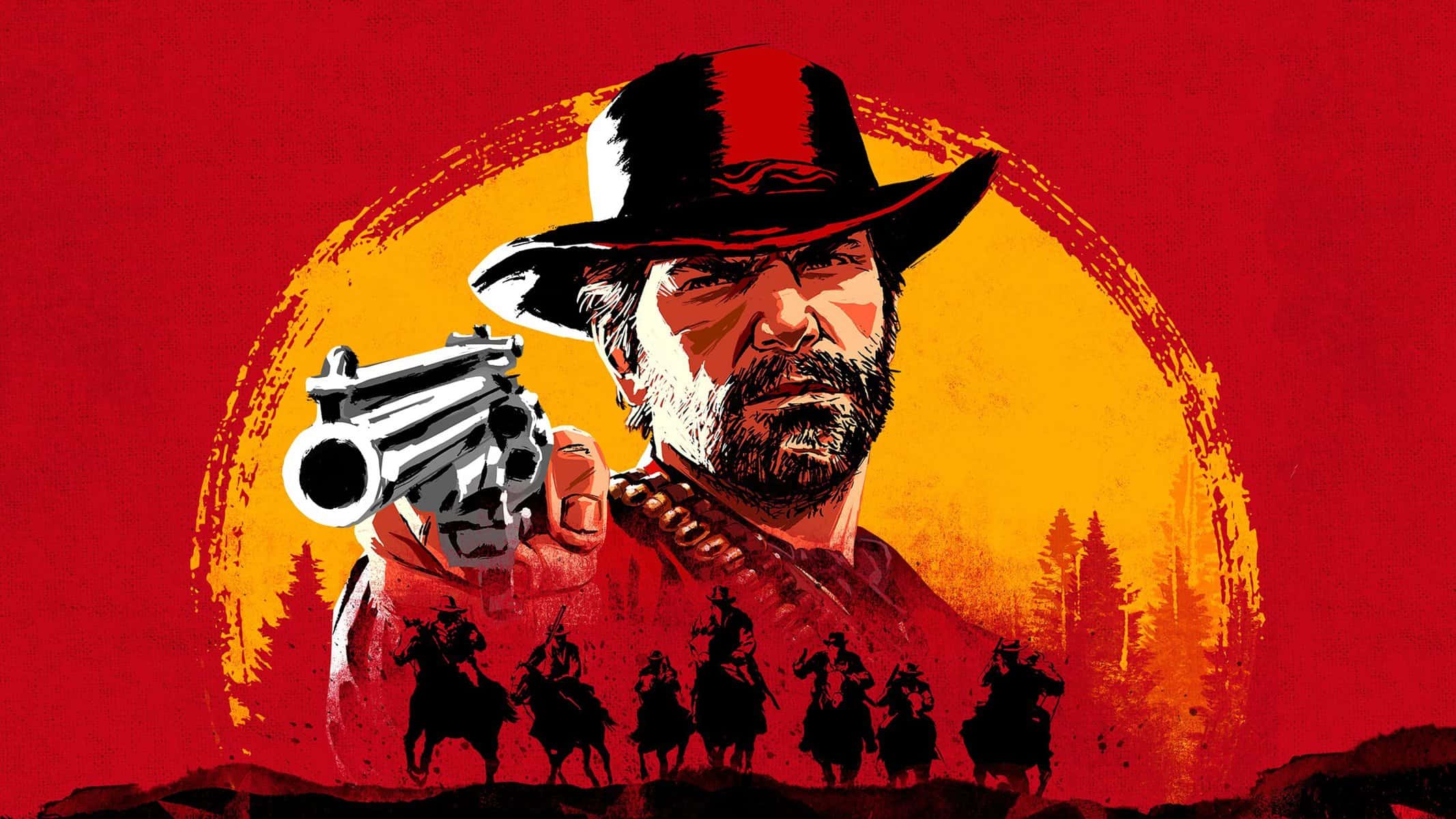

Red Dead Redemption 2

Canned kidney beans. That’s the secret to Red Dead Redemption 2. Every time the game’s hero, Arthur Morgan, eats kidney beans, I feel the tug of guilt as he tosses the can to the earth – for some hobbyist, a hundred years later, to find with a metal detector. After a certain point, our brains can’t process vastness; it loses its meaning. Rockstar understands that size is best communicated with intimacy. To go big, you have to go small.

A World like New Hanover isn’t easy to come by; it’s a far cry from the cities assembled by the creed of the click-drag texture fill. Every place in Rockstar’s American Southwest is distinct, from the red clay soil of Rhodes to the cozy log cabins and Twin Peaks cascades of Strawberry. What’s more, it isn’t honest. Despite the realism – the handsome facial animations, the aching attention paid to plant life – the game is impressionistic. The skies are violently blue, the rain biblical, and each sunset an oozing flood of amber, as if to trap the world in time.

The game is, at first, abstruse; it’s unceasingly slow and requires equal measures participation and submission. The leaden intricacy of its systems is dogmatic, but eventually it takes root and blooms in the mind. It’s narrative is an unwinding canister of 35mm Western iconography, from Leone to Eastwood by way of Peckinpah. But it’s the small things you feel, coaxed into life by this world and these people, that stay with you. Things like an empty can of kidney beans, rolling along in the dirt.

Dead Cells

There is much execution about Dead Cells. Not least of which because you wake in a dungeon, where, lurking in the background, an axe is driven deep into a bloodied chopping block. Nor is it just because, over the course of the coming hours, you dispense death with an array of grim tools. It’s also for the way the game executes on well-established mechanics with such precision so as to loft it above cliché into something new.

Most roguelikes that I play make me feel as if I’ve started over again, empty-handed but wise to their schemes. At each new release in the genre, the permaquestion hanging in the air is this: why? There are all sorts of ways to make death meaningful in games, but stripping players of all items and having them begin the game anew is, if done without sufficient purpose, vindictive and lazy. Dead Cells, on the other hand, was swift and sure in its purpose.

Your journey comes encrusted with trinkets that boost your powers, each run through saw you not just better prepared but better equipped. Throw in a tincture of metroidvania and the world begins to warp, new pathways opening and shifting to your whims. And what a thing it is to want to head back out, eager to get to cracking with the combat – which sees fit to reward as well as punish. In a genre stuffed with failed attempts, it’s reassuring to know that, at any time, success can strike.

Tetris Effect

Tetsuya Mizuguchi’s defining achievement, over the course of a career studded with sublime games, is making us all feel as David Bowman did when he plunged into the Star Gate, in 2001: A Space Odyssey. Of course, Mizuguchi musters forces that Kubrick couldn’t, wielding interactivity like an umbilical cord in a way no other developer has managed. He makes games that bathe the brain in sound and light, in which your nerve-endings come alive to shapes and sonic suggestions.

After the likes of Meteos, Lumines, and Every Extend Extra, there’s an inevitability to Tetris Effect, the feeling of something finally falling into place. In 1984, Tetris arrived fully formed, flawless in its execution and economy, and it’s taken 34 years for an improvement to come along. And yet, the defining characteristic of Tetris Effect is how little it touches Alexey Pajitnov’s design. Its biggest mechanical innovation is the Zone, a meter that builds as you clear lines; once activated, the blocks hang in the air, waiting for you, and dropping with muffled thuds. It has the same sweetness as cancelling social engagements – you’ve won back time.

The most meaningful addition, however, isn’t mechanical. Tetris Effect is named for the condition in which transfixed players might glimpse tetrominos at the edges of their vision or when they close their eyes at night. In his commingling of the aural and the visual, Mizuguchi pulls this sensation from the edges of the eyelids to centre of the soul. When you’re in flow, the images and sounds responding to your touch, you wonder where you’ve gone. Like the empty bucket at the game’s heart, it fills your head with ideas.

With all that said and done, there’s a sliver of sadness to pulling these lists together. I always look to the calendar, excited for the next year’s releases (2019 is looking very special), with a little regret at the way we churn on. Right now, all I want to do is go back to Saint Denis, to spin more blocks blissfully into place, and to drive fast through English fields. Indeed, there will be time.

Red Dead Redemption 2

- Platform(s): PC, PlayStation 4, Xbox One

- Genre(s): Action, Adventure