You can trust VideoGamer. Our team of gaming experts spend hours testing and reviewing the latest games, to ensure you're reading the most comprehensive guide possible. Rest assured, all imagery and advice is unique and original. Check out how we test and review games here

There is a curious pleasure in the jolt of a tonal clash. Consider the Alien prequel films, for example; in their obsession with tumbling down such dour existential wormholes as Why Are We Here? and Where Did We Come From? it’s easy to forget where we ended up. I wonder what the characters in Prometheus, mired in its ponderous gloom, would make of the sight of Sigourney Weaver and Winona Ryder squatting atop the rubble of a ruined future Paris, as they do at the end of Alien: Resurrection. They would likely presume it a parallel galaxy, an interstellar anomaly. Likewise the Resident Evil series and its separate strain of remakes, which slide back the tone, like the carriage on a typewriter, from camp to serious grit. Do Claire and Chris Redfield, the dutiful, jaw-clenching heroes of the Resident Evil and Resident Evil 2 remakes, realise where they’re heading?

The answer is an island in the South Pacific, the setting of Resident Evil—Code: Veronica. Although, it might not be. The recent rumblings suggest that Capcom may be turning its attention to remaking Resident Evil 4. The news caused many to enter a state of manic excitement, but for some it will have heralded an oversight. What, no second, sombre crack at Code: Veronica? There is an argument to be made that it’s simply too weird to be tethered to the graver tone of the remakes. How can you ground a game that begins with a helicopter chase and proceeds only further toward the clouds from there? On the other hand, it isn’t as though Resident Evil 4 is starved of the bizarre; if you’re going to attempt to lend gravitas to a game with a villain who sports a tricorne hat, then you’ll hardly struggle to straitjacket the eccentricities of Code: Veronica.

But the question is: why would you want to? To love Resident Evil is to be an enthusiast of the deranged, and Code: Veronica—which first arrived on the Sega Dreamcast, twenty years ago this week—has madness in its marrow. Its villain, for instance, is Alfred Ashford: a British nobleman, robed in naval red, with a helium-powered cackle, who—in a nod to Norman Bates—dresses up as his own twin sister. (If you want to invoke the sickly fug of the homicide-haunted family, who better to hitch a ride on than Hitchcock?) The narrative, too, has the loopy, logicless quality of a dream: the way the recognisable and the specific are pierced by the absurd. We follow Claire Redfield, as she pursues her missing brother to a Paris laboratory, gets wacked on the head, and wakes up in a prison cell on an island.

After the landlocked settings of the previous games—the areas in and around Raccoon City—Code: Veronica feels refreshing. At first you think, Oh, an island, that’s new! But then it dawns on you: a mansion wreathed by an ocean of trees, a police station trapped and lapped by waves of flame. These games, in their way, have always been set on islands. All of a sudden, you wonder if Claire has woken up at all, or if the haunted contents of her head have been rescrambled into a fresh vision of a familiar Hell. It could be Resident Evil’s answer to The Legend of Zelda: Link’s Awakening. Strange to tell, the odd effect of playing the game, especially with two decade’s worth of distance is a surreal clarity.

The plot of the average Resident Evil requires not only the suspension of disbelief but of scrutiny. The first three games were fuelled by a striving, B-movie tension and fogged by the low-lit machinations of their villains. The conspiracies of the Umbrella Corporation—which seems to operate with a bio organic mixture of boredom and malice—are covered in such layered darkness that keeping up can be exhausting, like wading through a muddy lasagne. Compare Code: Veronica, whose fringes are not patrolled by masked mercenaries or elegantly dressed spies, taking orders from crackling walkie-talkies. Its narrative, while still steeped in nonsense and knotted with the usual twists, comes alive with a crazed visual relish that would define—and damn—the next few games. When longtime antagonist Albert Wesker rears his head, we are relieved to find it jewelled with feline eyes, glowing behind his sunglasses. The image perfectly encapsulates the charm of Code: Veronica—of theatrical lunacy glimmering through the murk.

Indeed, without Code: Veronica you can’t imagine the flair of Resident Evil 4—nor, it must be said, the sweaty fever of 5 and 6, at which point we craved an antibiotic reboot. How odd, then, that most of the game is moth-brown and business as usual. It opens in a grey and drizzled barracks, and has you scrounging the shadows for keys and clues, while avoiding the rudely awakened dead. The place is the definition of drab: all chain-link fences and dirt paths, concrete walls and wooden annexes. And yet, there is something thrilling about it. Ask the average player about Code: Veronica and you’ll be met with a shrug, but ask a scholar of the series and you’ll see their eyes alight with archaeological glee.

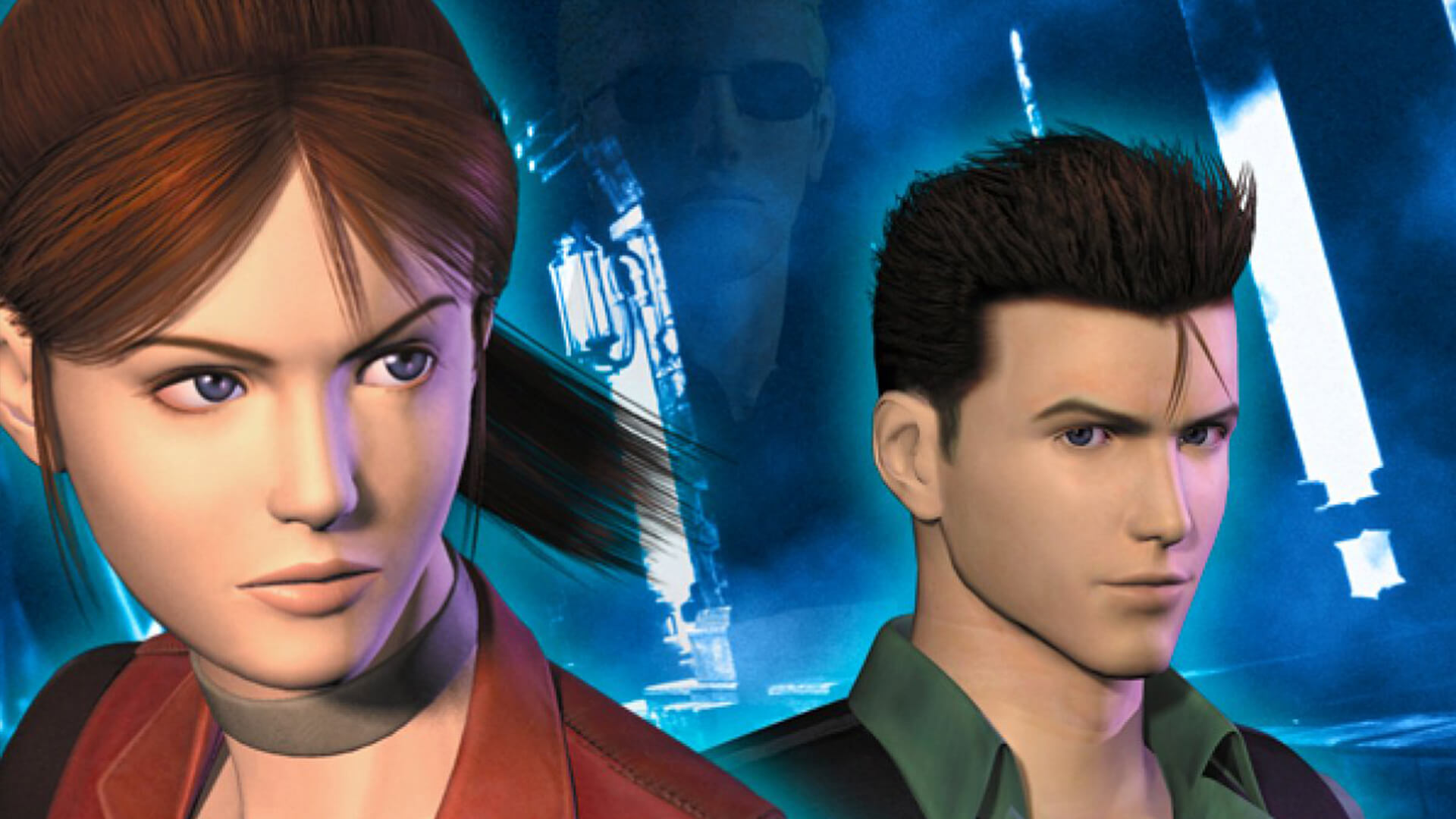

It was the first of Capcom’s survival horrors to enter the world of 128-bit. Courtesy of the Dreamcast, the pre-rendered backgrounds are gone, replaced by fully 3D-rendered environments, bathed in a brand new lighting engine. (The upgraded reissue, entitled Code: Veronica X, is available as part of the PS2 Classics range, on PlayStation 4, and I would recommend it over the HD version, available on Xbox One, for its soft-grained haze.) The graphics, certainly now, aren’t to everyone’s taste. The backdrops lack the sumptuous stitching of the pre-renders, and it’s perhaps difficult to look at Claire as kindly as one would have done in 2000. Her hair is a rough clump of brown, tapering into a polygonal ponytail, and her face looks pasted-on. She walks with a crusty, cattle-prodded gait, and turns on the spot like a lazy figure skater. But back then the visuals were a boast: a promise, made first by Sega, of things to come. And what remains, even as the graphics moulder, is the added directorial zeal they allowed.

Note the pan and swoop of the camera, into nooks and out into wide-shot corridors, allowing the developers—led by director Hiroki Kato, a protégé of Shinji Mikami—greater freedom to tinker with and tighten the suspense. The game retains the “tank controls” that the earlier games are both beloved and bemoaned for, and takes the term with a pinch of the literal, practically giving Claire armour-plating. You take a great deal more damage than ever before and can dual-wield certain weapons—flashes of the action-focussed approach that would define subsequent games. To puncture any sense of empowerment, however, enemy numbers have been upped, and the zombies—smeared in blood as bright as jam—respawn periodically, keeping you, somewhat cheaply, on your toes. Other details worthy of mention include a flurry of small firsts: the option to use green herbs upon pickup, should your inventory be crammed, and a checkpoint system, allowing you to retry some sections without loading up your last save.

Beyond these furnishings, though, is a simple proposition, grown more potent as the years have passed by: do you miss a particular kind of Resident Evil? Do your spirits sink when you hear that the eighth entry will be the “darkest and most gruesome” yet? Does part of you groan at the grim mood of the remakes, like a dream you want to wake from, if just for a while? My advice: do what I did. Spend the weekend celebrating a dim and distant patch of the series’ past, the likes of which we may never see again.

Resident Evil Code: Veronica X

- Platform(s): GameCube, PlayStation 2, PlayStation 3, Xbox 360

- Genre(s): Unknown