You can trust VideoGamer. Our team of gaming experts spend hours testing and reviewing the latest games, to ensure you're reading the most comprehensive guide possible. Rest assured, all imagery and advice is unique and original. Check out how we test and review games here

The following feature contains spoilers for season four of Game of Thrones and, weirdly, for the film Troy, which came out 15 years ago. Both are worth watching.

When rumours started swirling last week that George R.R. Martin might be working with FromSoftware, I thought Shuhei Yoshida had accidentally tweeted about the PlayStation 6’s launch line-up.’ So glacial is Martin’s pace that loyal readers await his books as they might a late thaw – their extremities numb, their teeth chattering with anticipation. Martin is, so the speculation goes, crafting this supposed game’s open world – which will be comprised of various kingdoms, naturally. (If there’s any justice, the map screen will unfold with the same whirring cogs as the show’s title sequence.) Each of these will be ruled by a boss, who, once felled, will yield new powers for the player.

Could it be true? Martin is almost certainly currently hooked up to an IV and/or living a monkish life in the mountains in order to finish the final two books in his series, A Song of Ice and Fire; where on earth would he find the time to write a game? And surely the cast-iron plotting and politics of his books – and, by proxy, the Game of Thrones TV show – aren’t suited to FromSoftware and studio head Hidetaka Miyazaki’s narrative approach, which is even more stark than Winterfell. On the other hand, there are some common flourishes of mood and tone between the two houses.

In the TV series’ official companion book, Inside HBO’s Game of Thrones, showrunner David Benioff says, ‘George brought a measure of harsh realism to high fantasy. He introduced gray tones into a black-and-white universe.’ What’s Dark Souls – a game in which your first encounter with a dragon is over as swiftly, and as gallantly, as a napalm strike – if not high fantasy bitten by harsh realism? And as for its world, Lordran – a crumbling kingdom under a sky like scratched pewter – the entire place seems eroded and half-swallowed by grey tones. Ned Stark would be in his furrowed, frowny element here, warning us, like a skipping CD, of the coming winter.

Of course, there is another similarity between Miyazaki and Martin: death. To watch Game of Thrones or play Dark Souls is to live in uncertainty. Each clash comes loaded with the weight of fate: the notion that any lucky lunge or ugly poke could spell doom. (How odd that in video games, the knowledge that death could arrive unannounced and blindside you is a source of such dread, when in life it’s the not knowing that sets us free – the better to indulge in such trivialities as the playing of video games.) Such has been the case in Game of Thrones since it began.

I remember watching ‘The Mountain and the Viper,’ the eighth episode of the fourth season of Game of Thrones, and feeling a pull in the pit of my stomach. There is a scene in which the young prince Oberyn, also called the Red Viper of Dorne, takes on Gregor Clegane, better known as The Mountain, who is loyal to the cruel Lannisters. The joy of the scene is soured by two things: the telegraphing of the episode’s title, which has the fabular feel of The Tortoise and the Hare; and the trappings of the plot, which demand that Oberyn lose. Thus it’s doubly dispiriting to see him so sunny and seething with anger, dancing around and openly defying the iron heft of Lannister rule, and doing so in such winsome fashion.

When we are finally treated to the sight of Oberyn’s pulped skull sprayed across the floor, we feel the way some of the spectators look, most notably Tyrion, whom Oberyn was defending. Freighting a fight with such crushing inevitability is something David Benioff has done before. When he wrote the script for Troy, he gave a similar scene the same disheartening undersong. The battle between Hector and Achilles is also heated by sun and flaring tempers. Achilles is thirsty for revenge and Hector, knowing he isn’t a warrior in the same class as Achilles, steps up to fight regardless. And he fares surprisingly well – well enough that our hopes hesitantly rise.

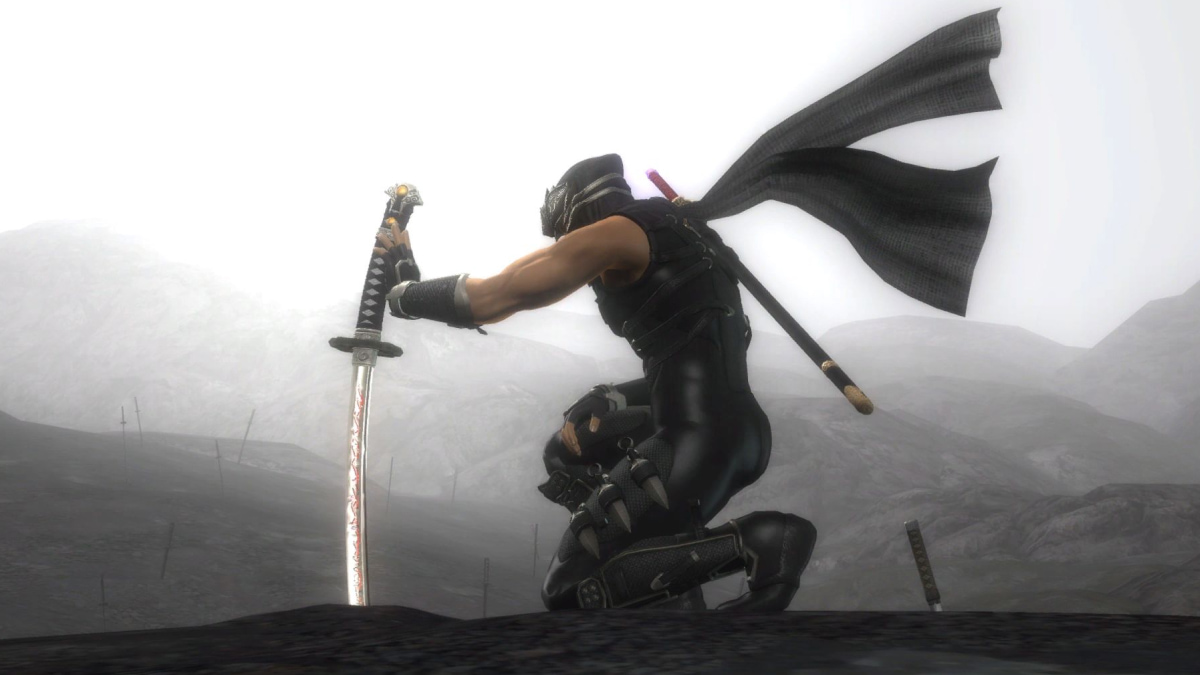

Because of the way death doesn’t favour the fair, both scenes instil a sense of not just tremendous skill – each is lithe and dancelike – but of bravery. And anyone who’s faced off against Vicar Amelia will know that feeling acutely: the need for courage the moment the cutscene ends and the bossfight begins; the need for calm, and decisive skill, in the face of chaos; and the knowledge that one whistling claw could mean the abrupt end to their valorous effort. (When I watch skilled players take on a boss in Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice, in a video like ‘Lady Butterfly No Damage Run,’ I feel equal parts reassured – the outcome being guaranteed – awestruck, and annoyed.)

Indeed, I was always of the opinion that the moment Jon Snow gasped back to life the show’s credibility began to ebb. FromSoftware pulled a similar trick in Sekiro – cutting death’s dominion by granting its hero the power to defibrillate himself back from the other side – and got away with it. The conquering of mortality is fair game for a game, it seems, but it’s the death of good drama. If George R.R. Martin is secretly squirreling away on a FromSoftware game, perhaps it won’t be as outlandish as it first seems. While his densley thatched plots and characters might hang heavy on Miyazaki’s weightless world-building, the two might mesh famously when it comes to killing us.