You can trust VideoGamer. Our team of gaming experts spend hours testing and reviewing the latest games, to ensure you're reading the most comprehensive guide possible. Rest assured, all imagery and advice is unique and original. Check out how we test and review games here

If you consider stubbornness worthy of celebration—and there are times when I can only admire it—then 2019 bore a rich brew of games, each of which seemed to have been prised perfectly from the knotty swamps of a single mind. June brought us Bloodstained: Ritual of the Night, created by Koji Igarashi, who decided that the solution to the overstuffed genre of the Metroidvania—which he helped to christen, with Castlevania: Symphony of the Night, in 1999—was to provide us with a Koji Igarashi Metroidvania. He was right. Bloodstained presents us with pared-back simplicity—a modest evasive hop, a clutch of spells—and its refinements are masked by the ruffles of its art style. It’s an exacting concoction of design, from a designer whose craft is vampirically impervious to age. The game began on Kickstarter, which, as its name suggests, has a habit of defibrillating dormant passions—which often have grown dusty for good reason.

Not so for Yu Suzuki, who used Kickstarter to help fund Shenmue III, the principal character of which was not its hero, Ryo Hazuki—who felt dry, lightweight, and stiff: all the essential qualities of cardboard—but the year 1999, which gave a performance of refined intricacy. Its prevailing theme is absence—of fathers, answers, and the teeming thrills of modern open-world games—a point crowned by the 18-year chasm between the game and its predecessors. Suzuki’s game had the odd combination of feeling both antique and timeless; its pace is sloth-slow, with a crush of mechanics now considered crusty, and yet it offers players a vision of freshness and focus. Suzuki understands, like the obsessive souls at Rockstar, that, in the building of an epic, the small stuff requires infinite sweat. Hence, in Shenmue III, the chores, the obsessive detail, the diversionary errands, the mingling of minigames into the repetitions of daily life. True massiveness can only take shape in the mind, and Shenmue III is, in a way, the biggest game of the year.

Whatever you do, don’t tell that to Hideo Kojima. Death Stranding, the first game to emerge from the deeps of his independent studio, Kojima Productions, grasps at a storm of subjects. The icy brinks of the information age, the quest for human connection, the horrors of ecological collapse, and the atrocities of video game marketing: weighty ideas, befitting a game concerned, above all, with weight. Despite the enormity of its themes, and Kojima’s eager churning of the hype machine, Death Stranding lives in the memory as a scattering of small moments, glimpsed while ferrying cargo through a damp gust in the late winter of life on Earth. I’m not so sure that a new genre has been forged, as Kojima so often declaimed in the run-up to the game’s release, but he has ended up with something perhaps no less impressive: he has fashioned an enrapturing game out of fetch quests.

Patrice Désilets, meanwhile, may well have actually set out to do that. Ancestors: The Humankind Odyssey came out in August, offering an array of quests but no discernible fetch. (Or rather the fetch was in such bewildering abundance that the quest was clouded with all-encompassing vagueness.) Ancestors deposits us at the dawn of man and tasks us with being true to our hirsute nature—by hunting and gathering. Leaves, rocks, sticks, fruit, and fire: grabbing at everything in sight fires up the neurons, turning the brains of your great apes into galaxies of twinkling progress. The trouble is that, much of the time, the game is an exercise (perhaps an authentic one) in tedium. And yet, there is an oddly captivating quality to it—something thrilling in its insistent obliqueness. At first, I chalked this up to there being nothing else like Ancestors, but it crept up on me that that wasn’t true.

Consider the special monkey-vision—called something like “intelligence mode”—which covers the undergrowth in dark hues and clutters it with icons. Then, there is the traversal, which, with a single button, has you capering through the canopy with ease. And finally, the gradual taming of a landscape through guile, good planning, and the merging of genetic memories. It’s Assassin’s Creed! Swap the sci-fi blather for a simple tale of hairy hardship, and all that stone and stained glass for tree trunks as wide as churches, and we’re back where Désilets began. This is what’s most intriguing about the games of 2019: spotting the marks of a singular vision made on works that have been whipped up by studios teeming with talent. What such distinction requires, I think, is a dash of megalomania—enough to stamp each facet of design with the recognisable creed of its creator.

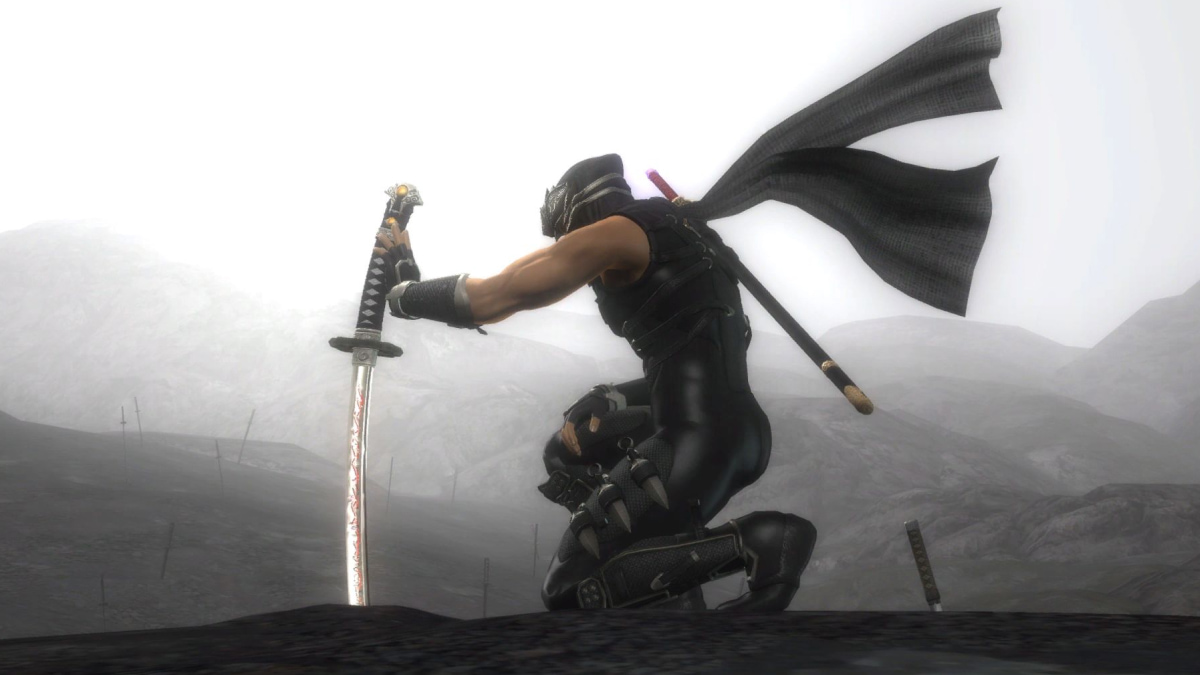

Take, for example, Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice, a game in which FromSoftware, the developer behind such breezy larks as Dark Souls and Bloodborne, decided to dash its own rulebook aside. From a team whose identity can be summed up with its most famous game’s tagline, “Prepare to Die,” Sekiro’s central mechanic, which gifts you the power of resurrection, comes with a tonic of irony—Prepare to Live! Further changes to the FromSoftware formula brush close with heresy: gone are the governing stamina bars of games past, and present is that most modish of accoutrements, the skill tree. But of course it isn’t the mechanical differences, the strayings from the trusted and trodden path, that thrill us; it’s the moments in which, like the looping routes of Lordran, we arrive, with a rug pull, back on familiar ground.

The touch of Hidetaka Miyazaki—who gives off the aura not of a company president but of a daydreaming captain, perched in the crow’s nest of a ghost ship—is everywhere in Sekiro. He seems to be issuing himself a challenge: to see how far the rituals of play can be bent without breaking the richness of the mood. Thus the ravening speed, the grappling-hook flights, and the shades of predatory stealth do nothing to disturb the unsettling aromas of Miyazaki’s obsessions—of rot buried under beauty, of stories delivered half-digested, and histories mingled with myth. That Sekiro should be one of the best games released this year is not solely down to its bearing the claw-marks of Miyazaki’s direction; it is the work of many hands, and a slew of other games sprang forth to remind us of the alchemical sense of identity that some studios have.

If you were unsure of who made Control, and you were to set a stopwatch ticking as you started it, I wonder how long it would be until you realised it was a Remedy game. Would it be the opening shot, seconds in—of a colour-numbed New York street, fog wafting from its flues, the monotone suddenly broken by the blaring yellow of a passing taxi? Maybe it would be a minute or so in, when you heard the noirish narration of its heroine, Jesse Faden? Or a little after that, when you get a feel for the feverish movement—the way the gentlest touch of the analogue stick has Jesse jogging down the corridor. I started Control with a smile on my face, as if I were being wrapped in familiar fabric that had slightly faded from memory. The developer’s name, which smacks of the medicinal, is perfectly chosen.

It’s always struck me that, if Remedy’s games have the feel of movies, it’s not because they are filled with homage; it’s because the most powerful creative presence involved in their making, Sam Lake, is only a writer—he occasionally directs, but only once, with Alan Wake’s American Nightmare, has he done both. It falls to Lake to plunder scraps of pulp TV and film and hammer them to the page—to blast his brand of dry ice through the steel grill of a studio framework. So much of what makes Control as captivating as it is is down to its art direction, by Janne Pulkkinen; its animation, lead by Ilkka Kuusela; and its trippy cinematics, directed by Mikko Riikonen. These are distinctly separate disciplines. Control draws its power from a deep pool of artistry and technical flair; to quote the final line from Alan Wake, “It’s not a lake. It’s an ocean.”

Which brings us to the first of two final games, The Legend of Zelda: Link’s Awakening, which begins on storm-tossed seas and ends under clear skies. It was made by Grezzo, a small Japanese studio for which I hold the same awed reverence I have for undertakers, whose duty is to dress and prepare the departed to be seen once more. Link’s Awakening was first released in 1993, for the Nintendo Game Boy; Grezzo, in other words, had artistic freedom to summon a style of its own to supplant the creamed-spinach visuals of the original. This meant that the game that awoke on the Switch, in September, had a double-whammy of advantages: first, its chassis was machine-tooled in a time that demanded perfect, spartan design, that couldn’t rely on sheer sprawl; and second, now that it had more lush tools at its disposal, it could bind us with the spell of its visuals—a kind of toyish plastic sheen.

After developing Ocarina of Time 3D and Majora’s Mask 3D, it should come as no surprise that Grezzo understands the business of buffing the rough edges of our memories. But Link’s Awakening could only have been done by a developer with as much gentle respect as Grezzo—a team of studious souls who leave the quests and clues untouched, expressing themselves through the game’s art style, whispering to us what we’ve always felt and reminding us of the simple wonder of what we are doing: playing with toys.

And so we end where we began: a chilly January brought us the remake of Resident Evil 2. The giddy excitement that stirs when we revisit the past is an odd thing, and there is no one better at stoking the hysteria than Capcom. The developer has the knack of nudging a game back into the spotlight at just the right time; it understands that some things should only be dusted off when the dust has grown thick enough. To play Resident Evil 2 in 2019 is to be solemnly reassured that the door to bygone days is forever left ajar, and that the future will always come frosted by the past. I knew I was in good hands about a 30 seconds in, when the first thing that greeted me was not a zombie but something far more sinister: darkness. At once it was clear that Capcom knew that the key ingredient of remembrance is shadow, with which we obscure and romanticise the real.

So it was that I spent the start of the year casting Leon S. Kennedy’s torch through the murk of the Raccoon City Police Department. The game, directed by Kazunori Kadoi and Yasuhiro Anpo, strims away the blockbuster bloat from the series and treats bullets like semi-precious stones. Given that the series’ iconic warning could have been tweaked, in the original, to, “You have once again entered the world of Hideki Kamiya,” its a wonder that the remake captures so much of its essence without succumbing to Kamiya’s near-fascistic obsession with baroque-chic style. It is, unquestionably, a Capcom game through and through, powered by the eeriest engine on the planet and tailored to within an inch of self-awareness. I can’t imagine it coming from any other studio, just as I can’t imagine Capcom doing it any other way, or surrendering to any single will. You could almost call it stubborn.

Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice

- Platform(s): PC, PlayStation 4, Xbox One

- Genre(s): Action, Action Adventure, RPG