You can trust VideoGamer. Our team of gaming experts spend hours testing and reviewing the latest games, to ensure you're reading the most comprehensive guide possible. Rest assured, all imagery and advice is unique and original. Check out how we test and review games here

The new Koji Igarashi game, Bloodstained: Ritual of the Night, begins as you would think it might. Mists swirl, a castle grows out of the gloom, demons get to work, and the people are in grave danger. Not too dissimilar from the game’s development: the project is posed, a studio springs up, its developers work like demons, and the people are in grave danger of being let down at launch. Such is the risk of Kickstarter, which is where Bloodstained began and where people pay to have their aching memories massaged. The ache in question is for Castlevania: Symphony of the Night, the game Igarashi made for the PlayStation in 1999. It told a tale of vampires in lacy luxury that helped christen a new genre – that of the Metroidvania – but failed to suck enough money from the public’s neck.

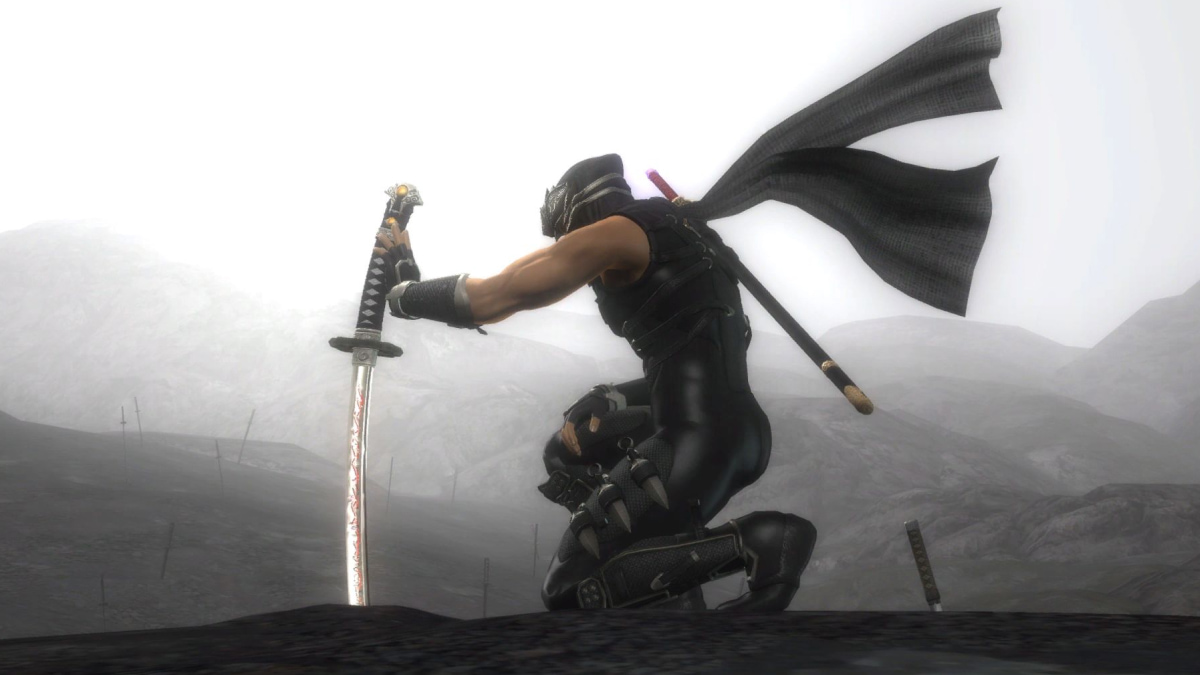

As you start Bloodstained, you are treated to a voiceover from David Hayter, whose vocal chords still sound cigar-scarred from his days as Solid Snake. ‘The Industrial Revolution ushered in a new era,’ he begins, with a dainty English lilt, and already the metal gears start grinding. ‘This marked the beginning of the era called the Cold War,’ began Snake Eater, and it’s as though Igarashi is intent on inhaling the fumes of Konami’s golden years. (Later on, Hayter voices a mysterious ninja who wields a katana, just like the one he fended off, all those years ago.) Before long, we are told about the ‘Shardbinders’ and the demons and all manner of mythology that seems to have been combed, by a coven of lawyers, for any trace of the words ‘vampire’ and ‘vania.’

Posed against the forces of darkness is Miriam, which is a terrific name for a protagonist, and I propose we demand similar names from future games: bring on the Barbaras, the Arnolds, the Ednas, and would a Dougal or a Reginald kill you? Miriam looks as though a stained-glass window had snuck its way into her family tree – a rash of coloured shards covers her body, and from these she draws magical powers. She can summon enormous rats, bats, and great balls of fire; she has a lithe backwards hop, which, though unmagical, yanks her free of danger; and she hoards a trove of weapons. The combat is, much like it was in Symphony of the Night, uncluttered and satisfying, with a need for peeled eyes and poised fingers.

There is also, I’m pleased to say, a fierce devotion to couture, with blouses, hats, and heels for the amassing. After turning my nose up at the notion of Bloodstained, and at Kickstarter rehashes in general, I came to a sober realisation: I can harbour nothing but love for a game in which a scarf increases my defence against a battle mace. And it’s this, as much as anything else, that locks Bloodstained in step with Symphony of the Night. That game’s charm wasn’t only its great clattering castle; it was the flattery of its approach. It beckoned you with faux complexity, making you feel enormously clever, as if you had just grappled with an arcane tome and emerged with a headful of occult knowledge – when, in fact, all you had done was see which weapon had the highest number next to the ‘ATK’ stat.

I’m still not convinced that Symphony of the Night ever required its RPG elements, but they seemed in keeping with its overgrown baroque ruffles; in a world where blood is sipped from wine glasses, why not? Its particular brand of too-muchness was intoxicating. Likewise, in Bloodstained, it’s pleasing to see your foes bleed bursts of numbers – the higher the better, naturally. There is a peculiar pleasure that lies not in being surprised, but in spotting a game a mile off, strapping on your armour, and still being won round. Partly, it’s a reassurance that good design – though dimmed as the years drift by – lives on, and it’s also a wonderful thing to see a talented creator get back to his craft.

The only trouble with Bloodstained is time, and the habit it has of passing. There has been a recent rush of Metroidvanias (Ori and the Blind Forest, The Messenger, Hollow Knight, Gato Robato) some have taken steps, small and sizeable, to usher the genre onwards, but it still feels crowded and creaky. Bloodstained is lodged in an awkward alcove – a new game cast in an old mould. As you gaze back from now, Symphony of the Night only shines brighter; it seems to have the advantage of immortality, enshrined in lavish pixel art on the console generation that ages least gracefully. It also enjoys a position of influence and standing that doesn’t diminish, like Dorian Gray in reverse: it’s locked, ageless, in the attic – a portrait without ruin – while its genre shows the strains of age.

Bloodstained: Ritual of the Night

- Platform(s): Android, iOS, Nintendo Switch, PC, PlayStation 4, PS Vita, Xbox One

- Genre(s): Action, Adventure