You can trust VideoGamer. Our team of gaming experts spend hours testing and reviewing the latest games, to ensure you're reading the most comprehensive guide possible. Rest assured, all imagery and advice is unique and original. Check out how we test and review games here

If you want to get your game off the ground, Kickstarter is all well and good, but you’re only covered for the initial kick; any further pokes, prods, or encouraging pushes are up to you. This knowledge will be fiercely felt by those at Cardboard Computer, the developer of Kentucky Route Zero—a surreal five-part point-and-click adventure game that has, since 2013, been dropped into the jaws of ravening fans scrap by scrap. Stashed throughout are insights into the travails and triumphs of such a long development time; one diversion takes us to an art gallery, in which a plaque reads, “Some of their debuts collapsed under the weight of logistics, only to be successfully executed much later.” You could read that as an admission of folly, or flimsy planning. On the other hand, the sequence is set in an art gallery, implying that worthy work is not to be rushed.

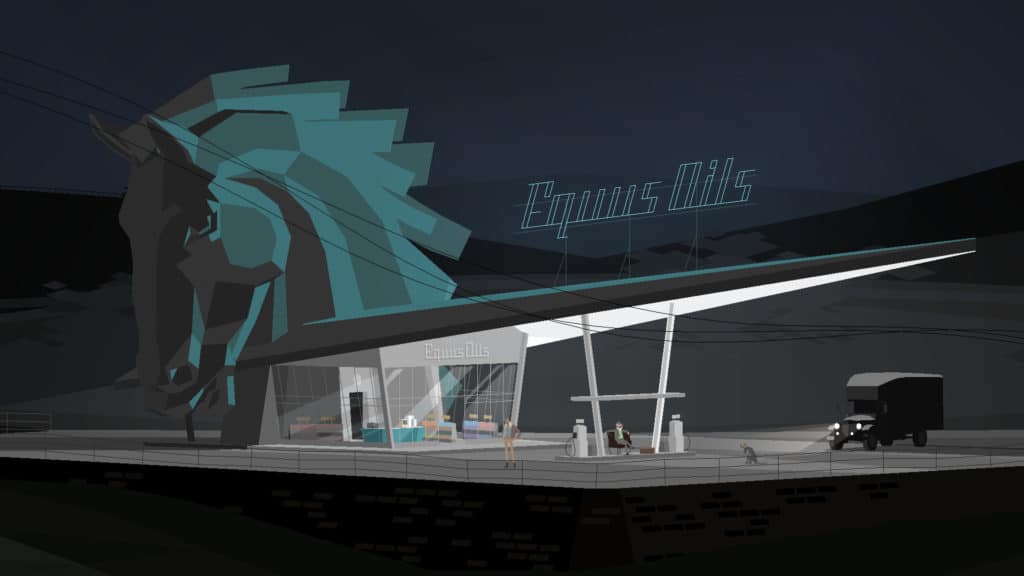

We follow an antique delivery driver called Conway, who, accompanied by an ash-coloured dog in a straw hat, pulls into a petrol station at sundown, searching for directions to an address. He looks, as all the characters do, like one of those forlorn figures that haunt the edges of Hopper paintings. The game is flush with American art; you need only glimpse the garage, Equus Oils, with its enormous metal horse head, silhouetted by a burning sky, to be put in mind of “Standard Station,” by Edward Ruscha, who was driven to pluck out and print such an essential American symbol after journeying on Route 66. Conway is informed by the pump attendant that he will need to take the Zero, a mysterious hidden highway whose surfaces seem to be paved with a mixture of asphalt, metaphor, and quite possibly magic. The plot, despite having the benefit of a clear on-ramp, soon becomes just as elusive.

Conway collects a number of others on his travels. There is Shannon Márquez, who repairs old televisions and whose emotional antenna seems more attuned to what’s going on than most everyone else; Ezra, a young boy bouncing with naïve energy, who claims that a giant eagle, named Julian, is in fact his older brother; Junebug and Johnny, a pair of robot musicians who race through the night on a blaring motorbike; and numerous others who shift onto the stage and back into the shadows. Indeed, it isn’t play of the video game variety that fascinates Cardboard Computer; it’s the theatrical kind. The tale cuts swiftly between tellers, giving you dialogue choices for most of the characters. This isn’t so much to bend and divert the flow of narrative—which, like most of the conversations, consists of tributaries of non sequitur—but rather to season your preferred flavour of weird. The winding of each inner monologue is often up to you, and it lends the story a democratic spice.

It isn’t without a sizzle of irony, then, that what consistently floored me was when Kentucky Route Zero broke the fug of stage-play static and swung into motion. Witness the wooden slats of a house sliding away and the night outside pouring in, or, as you move through a cavernous museum, the way the camera spins like a mobile to reveal a row of houses harboured in its metal rafters. It’s as if a crew of stagehands was darting from the wings to shunt the scenery into strange new alignments. All the world’s a stage—better yet, it’s one with wheels! I came away from some scenes feeling etherized by the art style: the light is a muddy stew of coffee-browns and powdery, twilit blues, while the trees and clouds are cut from a pattern of drifting diamonds. The abstract drowsiness of it renders moments of unreality all the more digestible, too; we think nothing of an eagle the size of a house spliced between trees, in homage to Magritte’s “Le Blanc Seing.”

Beyond inducing a pleasant daze, the visuals bear an important reminder: that surrealism, at its best, bypasses the railings and relays of the brain and strokes the nerve endings. Furthermore, it coheres in the gluey grip of emotional logic and hums with its own sort of sense. But by the time I got to Act III, in which Conway and the gang arrive in a hollowed-out mountain and encounter a computer called Xanadu, I came to the slightly cross-eyed conclusion that I had spent too much time in my own head, combing through slabs of text stuffed—and stuffy—with literary allusion. It isn’t often you come across a game that feels free to reference Robert Frost, Flannery O’Connor, and Samuel Coleridge; but, while it’s lovely for literature buffs, it doesn’t serve the pacing, which meanders with a mazy motion into detours that feel measureless to man.

Those intoxicated by the game’s dreamy brew may argue that there are no detours—that, like the Zero, you’re either on it or you’re not. If you’re anything like me and Conway, however, you’ll be somewhere in-between, with restless stretches spent looking for it. The game’s creators describe Kentucky Route Zero as a “magical realist adventure,” and your enjoyment will depend on which way you want the balance skewed. I happen to like my magic in manageable doses when it mingles with the real. Take the Coen brothers’ O Brother, Where Art Thou?, for instance, which earthed Homer’s Odyssey in the soil of the American South; its hints of the fantastical were low-key and clipped, knowing full well that modernity can’t dent the recurring power of myth (any more than it can excuse George Clooney’s oily eyebrows). Kentucky Route Zero tips the other way, but it doesn’t leave the ground behind.

The sights and smells on offer in the later acts, and in the four short interludes wedged between them, all contain a trace of that petrol station: of the outlandish and unlikely deeply rooted, and drawn up from the landscape. The villain of the piece is the Consolidated Power Company, which—driven not by ambition but its vacuum-powered reverse, the urge to own—buys out the Hard Times Distillery. While the message (small communities=good, big business=bad) might feel a little pat, I won’t soon shake from my mind the distillery’s employees: luminous golden skeletons whose bones buzz like neon. There is also a fetishy sentimentality for analogue technology, but what else would you expect from a developer called Cardboard Computer: a name that betrays a longing to see the complicated circuitry of the present fashioned from the simple, stiff pleasures of the past. None of my criticisms will be new to the developers, either, who have worked for a decade and are nothing if not self-aware; in one moment, we read a local newspaper review of a striving theatre production, which is described as “an absorbing, if unfocused, drama about the ills of debt and dishonesty.” Quite so.

Developer: Cardboard Computer

Publisher: Cardboard Computer

Available on: PlayStation 4, [reviewed on], Xbox One, and PC

Release Date: January 28, 2020

To check what a review score means from us, click here.

Kentucky Route Zero

- Platform(s): iOS, Linux, macOS, Nintendo Switch, PC, PlayStation 4, Xbox One

- Genre(s): Adventure, Indie