You can trust VideoGamer. Our team of gaming experts spend hours testing and reviewing the latest games, to ensure you're reading the most comprehensive guide possible. Rest assured, all imagery and advice is unique and original. Check out how we test and review games here

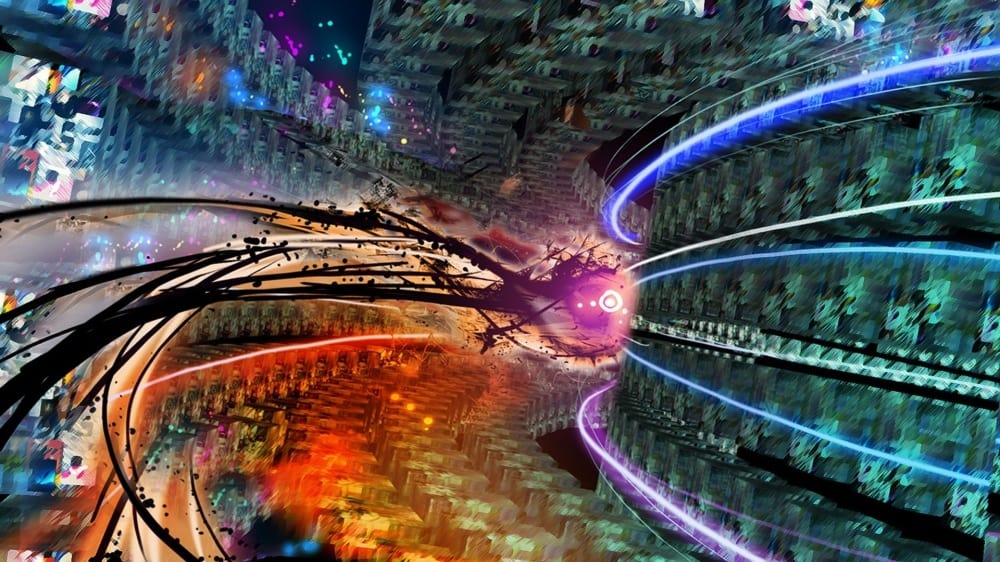

Maybe, just maybe, Child of Eden has the best main menu screen of all time. Standing in a digital enclosure peppered with pulsating shapes and peculiar sea-creatures is Lumi, the child of Eden. As she stands there, staring out of the screen, you can directly interfere with her environment. Run a hand through a shoal of jellyfish (or what appear to be jellyfish), for example, and they’ll effervesce with colour, producing melodic cries to accompany the ambience of the dream-like space. It’s like a toy-box of organic musical instruments, and it took all my energy to leave it be and start the game proper.

Kinect feels like a good fit for Q Entertainment’s upcoming music-shooter, a genuinely well-integrated use of the technology rather than a needlessly tacked-on gimmick. After watching Tetsuya Mizuguchi, the creative brains behind the game, demo the first level, I was pretty sure I knew what I was doing. Right hand for locking on, a thrust forward to fire at locked on targets and left hand for unleashing a stream of projectiles – the Tracer, as it’s known. If you’ve collected the appropriate power-up, throwing both arms into the air will activate Euphoria, a move capable of destroying a screen-full of enemies at once.

As an enemy disintegrates into fluorescent shrapnel, a short burst of sound rings through cyber-space. This always happens in congruence with the music, giving an impression that you’re some sort of omnipotent space conductor. The feeling will be familiar to anybody that has played Rez.

In terms of sensory involvement, Child of Eden is certainly an improvement on its spiritual predecessor, with fantastic visuals and a fitting soundtrack. Despite being built from abstract shapes and strange floating architecture, there’s no denying that the game looks beautiful. The music itself is excellent too, all mellow J-Pop with trippy drum loops and haunting synths. The ever-changing nature of the environments, the combination of colour, shape and sound – it’s all completely nonsensical, but thankfully the narrative allows it.

The basic premise is as weird as it is wonderful. In the future – 250 years or so, says Mizuguchi – the first human, Lumi, is born in space. When she dies, her consciousness is put into digital storage by scientists, and then integrated into Eden, a next-gen internet of sorts. As an omnipotent being floating through this tangible cyber-space, it’s your job to save Project Lumi (as she’s known in her digital form) from a virus attack – thus preventing the destruction of the first internet life form. Interestingly, Lumi is also the face of Genki Rockets, a mysterious hybrid band which Mizuguchi has some involvement with. The group will also be lending their musical talents to the game.

That’s the gist of it, anyway. Mizuguchi was playing as all this was explained to me, and although I tried to take coherent notes (oh God I tried), my efforts were largely futile. This is one of those games that’s incredibly hard to take your eyes off, so when I referred to my notepad to type up this preview, I was met with an assortment of strange scribbles that barely resembled words at all.

Each level in Child of Eden is referred to as an Archive, a layer of Lumi’s conscious that takes on a life of its own. Matrix, Evolution, Beauty, Passion and Journey comprise the five layers of her being, although Mizuguchi teased that meeting certain requirements could unlock a hidden sixth area too. Each Archive has its own unique aesthetic, enemies and bosses. Beauty, for example, is brought to life with soft pink hues, butterflies and floral enemies firing off spore-based projectiles. Passion, on the other hand, was more industrial, built from gears and intricate mechanisms, with mechanical birds loitering the skies, teasing your reticule.

Towards the end of the session, I surrendered my body in favour of the cool hard plastic of a control pad. It’s a strange logistical complaint to make, but holding your arms out in front of you for extended periods of time can start to ache. This problem will likely disappear as your muscles acclimatise to the movements, of course. Despite using the technology well, I couldn’t escape the feeling that the game was a better fit with a pad. Navigating the screen with an analogue stick is simply easier than with floaty limbs. It’s much easier to snap onto enemies, too, and unloading your weaponry feels far more natural.

Don’t get me wrong, Kinect works just fine, but those serious about their rhythm action shooters (and there’s a small army of them) will adopt the pad fairly quickly. I’m intrigued to see how the Move-enabled PS3 version compares, but this option was not something available to me when I saw the game.

Ultimately, words fail to do it justice. Like Rez, Child of Eden is an incredibly sensory experience. It’s strange that, what is essentially a shooter, can be so relaxing. Amidst the flurry of projectiles and boppy music, there’s a inexplicably meditative quality to Child of Eden. It’s a strange game, for sure, but at the same time one of 2011’s most interesting titles.

Child of Eden is available for Xbox 360 and PlayStation 3 in June

/https://oimg.videogamer.com/images/9879/child_of_eden_2.jpg)