You can trust VideoGamer. Our team of gaming experts spend hours testing and reviewing the latest games, to ensure you're reading the most comprehensive guide possible. Rest assured, all imagery and advice is unique and original. Check out how we test and review games here

It seems like the dream job. But is testing games from the likes of Rockstar, EA and Sega really all it’s cracked up to be, and what does the next-generation mean for one of gaming’s most misunderstood roles?

Getting into the games industry isn’t easy. Many years honing your craft are required, and even then you’re not guaranteed to get a job unless you can prove your abilities by, for example, making a game. It’s a catch-22 situation, but there are other ways in. One of them is via testing, and many young hopefuls turn to it to try and move up the industry ladder.

Quality assurance – or ‘game testing’ – is a dream job for many. It’s a career that’s difficult to enter, not because the barrier to entry is high – with the bare minimum of academic grades required – but because the (mostly unrealistic) desirability of a life playing videogames all day leads to a bloated mass of applicants applying for each opening.

Once you’re in, however, it quickly becomes apparent that testing is one of the most demanding, laborious, and downright cliquey jobs the industry has to offer: a strange mixture of exclusive boys club and low-paid donkeywork. It’s also a revealing look behind the curtain of game development, an at-times unbelievable education in just how – and why – your favourite games end up as they do.

And while the games in question may change, the stories from these demanding, clandestine environments stay mostly the same. I sat down with an ex-QA tester, to find out what life was like at one of the biggest names in the industry, Rockstar Games.

(I shall refer to our interviewee as Barry, as he asked not to be named… and nobody is called Barry.)

It all began when Barry saw an advertisement in the local paper and decided to apply for it on the off-chance. Sure enough, he got the job. He had a Higher National Diploma in computer studies, which he’s sure helped him stand out from the leaning tower of candidates, but it certainly wasn’t essential.

Barry went into the interview completely blind – he didn’t even know anything about the company, other than the fact that they made the Grand Theft Auto series. At this point in time, GTA3 had just been released, proving to be a massive success for the company with the game redefining the term ‘open-world’ and the franchise’s name becoming synonymous with the genre.

The first game he worked on was 2K Czech’s squad shooter, Hidden and Dangerous 2. His experiences may have been confined to working for 2K, but what he told me is an almost like-for-like replication of how other big publishers handle their testing teams.

During his early days at the company, testing was less structured, with testers being assigned to perform playthroughs on a set difficulty of the game they were working on. Some of the testers would play through the game as a ‘customer’, without trying to trigger any bugs, while others would be assigned a set level – depending on time constraints – with the objective to scour every corner of the mission, trying to ‘break’ it.

As well as playing the same level for a whole day, the versions being used were early builds of games described as “shaky at best”. Countless problems would crop up, not least the constant procession of freezing issues (when your game suddenly stops and won’t continue, it’s called a ‘hang’) to full-blown crashes. On top of this, the games would often feature placeholders for visual effects, with text and dialogue commonly being missing. For people accustomed to playing stable retail releases, it can be a shock seeing the guts of a game on show. ” It’s certainly a far cry from playing polished games all day,” explains Barry.

The team would encounter different types of bugs, each classified by severity: Class A bugs represented the showstoppers: crashes, lockups and so on. Class B bugs focused on errors that prevented the player from continuing a mission, an example being an area that asked a player to clear an area of enemies, but one has spawned within a wall…

/https://oimg.videogamer.com/images/3b96/gta_iii.jpg)

As he learned the intricacies of the job, Barry also started to notice the difference in the working environment from past roles. There was a sense of intimidation at first, although he insisted he was made to feel welcome. This intimidation came from being a stranger in a pack of similarly-aged males – female employment in test has been known to be shockingly low in certain companies. As such, the office had a “boys’ club” vibe, with the staff forming a tight group, making it feel like new recruits were “entering someone else’s turf”. Instead of being clinical, the office was adorned with posters and scattered with memorabilia. The workforce was encouraged to personalise their workspace.

(Barry also said this wasn’t always the case in QA: “This personalisation wasn’t the same everywhere – I’ve heard of some of the big boys having their testers segregated into lines of cubicles.)

“Human interaction was essential”, he says, “Especially when it was a critical point, like preparing for an E3 presentation. We would sometimes do seven day weeks, while also working extended days.”

Depending on the pay structure, employees wouldn’t always get overtime for the extra hours, either. As the games got bigger, this became a more common occurrence, too. It often meant working on a single title for a longer period of time.

“When the current generation of consoles shipped, there seemed to be a shift” Barry continued. “And the long tail end of the project would carry on forever, with the testing of patches and extra content.”

This shift occurred when the QA facility changed from testing 2K, Take-Two and Rockstar titles, to being exclusively Rockstar-focused. This resulted in them working on single titles for years instead of months. “This is probably truer now,” Barry says, “with the rise of downloadable content”.

There was one title that stood out for him and, strangely, it came in the form of Virtual Pool. He tested the sport sim for a year… and despised it. “If you ask any tester, they’ve all got one that stands out” he admits. “One they hate.” It was a game that, for Barry, no joy could be extracted from.

Most of the testing surrounded taking a physical recording of statistics and seeing if they matched up with the game’s stat tracker. “This was monotonous enough for a day”, he adds. “Now imagine doing it for a year. The first version we played was a pool game, and that’s what it ended up being… a pool game”.

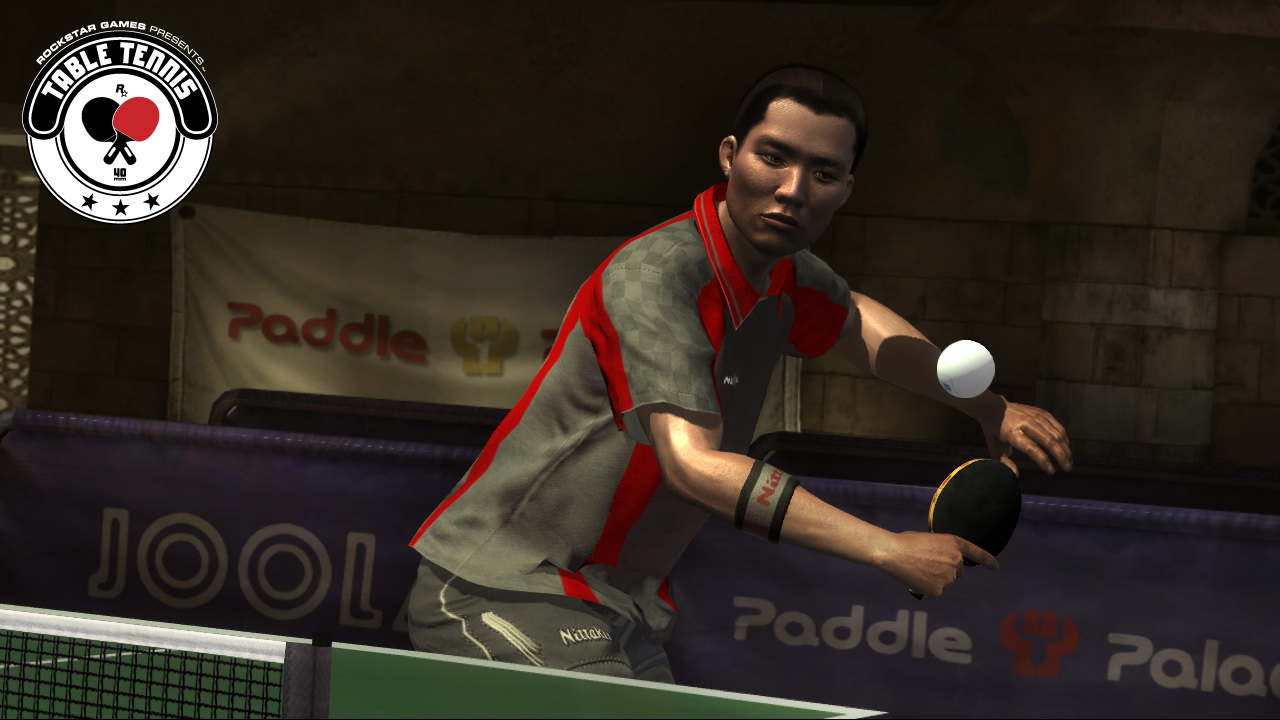

On the opposite end of the spectrum, though, there were games that were far more entertaining, one being Rockstar Games Presents: Table Tennis. The title, a sort of a side project for the company, was a good way to test the RAGE engine in preparation for what was coming next.

“It had an old-school, arcade quality to it and they got the controls spot on. Also, with it being multiplayer focused we got to test it together, which always heightens the fun.”

So, like any job, quality assurance has its highs and lows. It’s just that each extreme is a long, drawn out process. Many look past the monotony, however, as they see the job as a gateway into the industry. And to the privileged few, it does work out this way – as a stepping stone, with talent playing a huge factor in the outcome.

But it’s a long road. At the office where Barry worked, the testers had no direct contact with the development team – not even on the phone. It was all done through an in-house database, which fed directly to the development studio.

“We would sometimes get comments on the system from developers. You would get a little feedback that way, but to you they are just a name. You didn’t ‘know’ them.

“It is seen as a stepping stone into the industry, yes, but sometimes that’s not easy. It’s certainly not impossible, but of course that depends on where you are. I don’t know if it’s any different now, but it wasn’t like we got internal applications on the notice boards.”

There were opportunities for promotion internally, but it was just up the testing hierarchy rather than migration to a completely different area.

To many, though, the opportunity to ‘play’ games for a living is too much to resist. There does seem to be a misconception regarding game testing, and many see it as a dream job where they get to sit and play games.

“I think people do have the wrong idea about games testing,” admits Barry. “I mean, you’re sitting there playing games, sure. But not for enjoyment – you’re following a routine, trying to uncover issues.”

One of the biggest challenges was described as “bug revision” (sometimes called ‘regression’) and it took up a huge chunk of his time. Repetitive and at times monotonous, it’s up to a tester to duplicate an issue that has been reported previously within a new build. Without patience, most of individuals wouldn’t find much enjoyment in it.

One of the reasons Barry decided to leave was because of the repetitive nature of the work. “People just get tired of the monotony,” he says. “The periods of long hours didn’t help, sometimes twelve hour shifts, six or seven days a week. The pay isn’t fantastic either, it’s definitely towards the low end of the industry.”

The free merchandise and bonuses helped to ease the pain a little, he told me, but I couldn’t help think that a couple of branded hoodies wouldn’t make up for seven day weeks and a 14K starting salary. He said it made him feel like part of an elite group – he would spot people wearing the merchandise and see the Rockstar logos on stickers that had been placed around by other staff members. It plays into the exclusive vibe that comes naturally to QA work. You see – and play – the games first, and you encounter aspects of the game that no consumer ever will.

There’s also another perk, which is not insignificant for people who love video games: getting your name in the credits of the titles you work on. Along with becoming immortalised, a free copy of the title is also on the agenda given that you’ve been working on it for the past few years.

But surely most people wouldn’t ever want to even look at that game again?

“Not really, no,” laughs Barry. “A lot of people kept them as souvenirs, but quite a few would just take them straight down the shop and trade them in towards one of the new titles.”

The only game that he played after working on it was Grand Theft Auto 4. This was mainly because, when he was testing the game, he never really got to ‘play’ it at all.

“I was given areas of the map and then I would go round looking for any skewed or out-of-place textures. Scenery clipping through a building… stuff like that. My other task was to run around with a melee weapon and just hit things. I would hit them to make sure they made the right sound.”

This experience probably best encapsulates the testing world. GTA 4 was the most anticipated game in history at this point, with each day until release passing agonisingly slowly for fans. Barry was playing it, and yet most of his time with the game was spent running around with a baseball bat, hitting bins.

“There was also the way the weather affected the environment,” he continues. “In GTA4, when it rained there was a kind of specular highlight applied to the textures, giving everything a reflective sheen. This meant I had to check each area under different conditions. It was methodical, and kind of satisfying – certainly not taxing.”

So, what did they do during their downtime, I wondered. Go outside for some fresh air? Stare at a real sky?

“We would play some games,” Barry smiles. “In the break room we had a pool table and a fair few arcade cabinets.” So, game at work, game on your break and game at home – sounds good. “A lot of people can’t understand that, but sometimes you just want to put your feet up and play a ‘good’ game for a change.”

With regards to upcoming Rockstar projects, he knows as much as anyone else, and publishers go to great lengths to ensure it stays this way. “The security at the company is fantastic, and they’re good at plugging leaks. They treat security very seriously.” And Rockstar are the masters of secrecy. We live in a world where game announcements are preceded by leaked artwork, yet Grand Theft Auto always manages to only enter the limelight when Rockstar decides so.

It makes you wonder what kind of consequences one would face from leaking such information. “I can’t think of any instances where anyone did,” Barry says. “But you could say goodbye to your career, certainly. It makes me feel a bit anxious about this interview, actually. Not that I’m saying anything confidential, but Rockstar are very proactive with that sort of thing. They have people who just surf the web all day, looking for any leaks and then they can trace it back, and there would be repercussions.”

This comment made me wonder what these repercussions would be and, ultimately, this is why he is now called Barry.

Towards the end of his time with the company, many changes started to creep in. “In the early days, a lot of our systems and practices were put into place by ‘us’. There was no rule book on how to test games” he explained.

It seemed the company was evolving in tandem with the increased spending involved in next-generation game creation. “As years went on, and more money became involved, things became a lot more serious, sure. The circle of trust got tighter.”

The current working conditions are as much a mystery to Barry as anyone, but rest assured, the work itself hasn’t evolved too much. So, if you fancy a career where you get to run around a virtual world, hitting trees, bins, and cars with a baseball bat, you may want to give Rockstar a call. If you are serious about getting into QA work, though, it may be worth researching the potential companies first.

Volition, although now defunct, is where Drew Holmes – lead writer on BioShock Infinite – got his first industry job as a games tester. The possibility for advancement does exist. But there’s also a strange culture inherent to some QA divisions, one that relies on (and of course, pays) its testers for their work, yet at the same time distrusts them and treats staff with a sense of dispensability.

Next week, we’ll be examining just exactly how that affects the games you end up playing, and what the next-generation holds for the future of test.

/https://oimg.videogamer.com/images/446d/table_tennis_6.jpg)

/https://oimg.videogamer.com/images/82f7/grand_theft_auto_4_186.jpg)