Video Gamer is reader-supported. When you buy through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Prices subject to change. Learn more

When I met Ron Gilbert in London he’d just spent the previous couple of weeks touring Thimbleweed Park, the game he and Gary Winnick crowdfunded way back in 2014, for press and fans alike in Germany. He then spent half an hour demonstrating it for me, giggling at his own jokes in a very endearing way. As someone for whom the Lucasfilm games loom (har-har) large in their life, it was sort of surprising to see that Ron Gilbert — he who developed classic point and click adventure games like Monkey Island; architect of the instantly recognisable SCUMM engine — is not, as my childhood self assumed, some kind of actual wizard, but a regular dude in a flat cap who laughs at himself (and yet are we not all regular dudes?).

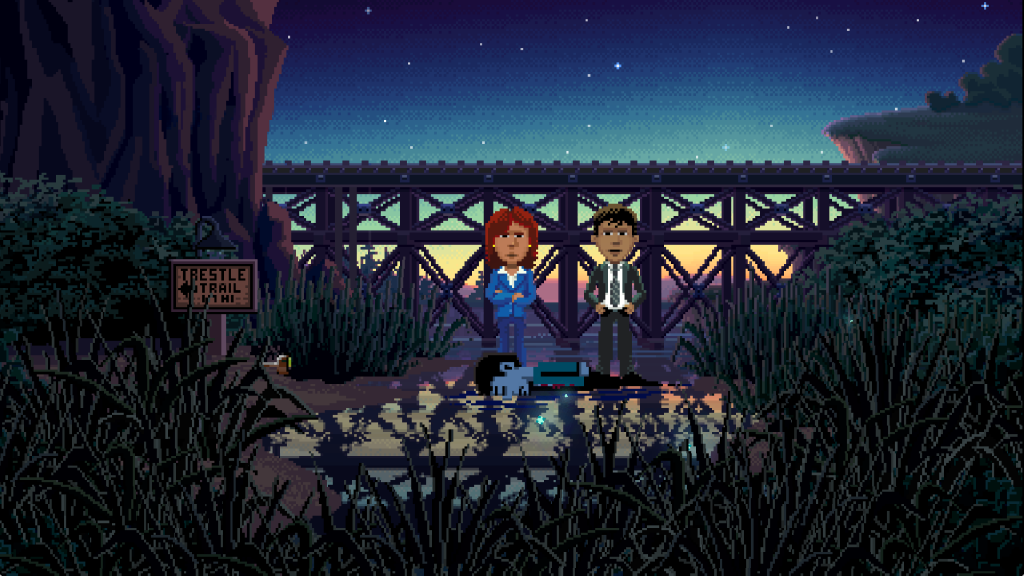

Thimbleweed Park is a point and click puzzle adventure modelled after the Lucasfilm/LucasArts games, but done better. ‘To us it’s like there’s a certain charm to those games,’ said Gilbert, explaining why they decided to make one of them again, ‘And as much as I love a lot of modern adventure games — I love Firewatch, I love Gone Home, Kentucky Route Zero, I liked all those things quite a bit — there’s just this charm that those old games have.’

They couldn’t isolate what that charm was, so they decided to figure it out by making a game like they had back then, but with the benefit of 30 years of experience and more powerful tech. It’s an attempt to recapture what was good about 8-bit adventures, not remake one. But that’s why Thimbleweed Park has, for example, a nine verb action menu and an on screen inventory — something Gilbert thinks he’d play around with in any future games, having decided it’s not a critical source of the aforesaid charm. So does he now know where it did come from?

‘I think I’m closer… To me the biggest thing is the sense of place. When you play Thimbleweed Park you really feel like you’re in this town. After you’ve been playing for a couple hours you almost feel comfortable there. You feel like you know this town and you know all the people, and Maniac Mansion I think was the same way’ — and here he became more animated — ‘That house right? You got to know that house. It’s like the world became your best friend in those old games.’

/https://oimg.videogamer.com/images/989c/67c87aea-618b-41e1-a218-0bbc8c0fe6c3_Bookstore.png)

My own attachment to them came from the superfluous details and hidden silliness. Games like Monkey Island taught me to be an inquisitive player, because you could try anything in them and get a response (usually a funny one). Gilbert is aware of this, and it’s also something they’ve tried to replicate in Thimbleweed Park.

‘When we were making those games back then I kind of likened it a little bit to improv development. We were thinking up weird stuff and we put loads of really weird things in the game just because we happened to think they were funny You’ll try all these weird things and you get funny responses and cute animations. It just kind of brings the world to life a little bit. I think you find that when you’re playing Thimbleweed Park.’

It is perhaps a testament to their success in this area that Gilbert was able to laugh despite having sat through the jokes countless times. But though the jokes are there, the player may not always find them. Thimbleweed Park is out to appeal to a broader audience this time, which has it’s own set of difficulties when a player isn’t used to just exploring on their own, without much direction from the game itself.

‘I think, especially in the mobile game world, players are so used to being told “You can now do this!” and they don’t really invite that exploration. There’s this little bit of a hump that new players kind of have to get over,’ said Gilbert, talking about playtesting with relative newbs, both to the genre and games in general. ‘I think it comes when they try their first weird thing and they get a funny response. And then they’re like “Oh. Oh!” and they break out of it and start doing that stuff.’

‘Our goal was to really bring this wonderful thing called point and click adventure games to a much broader audience,’ he said, animated again, buoyed up by enthusiasm, ‘Because clearly a lot of players today love narrative games, and I think point and click is a really great genre to tell stories and to do narrative.’

/https://oimg.videogamer.com/images/9a14/8fcd8270-0f55-4f06-a955-05fab2f1e685_QuickiePal.png)

To me Thimbleweed Park exists on the same kind of blurred line as pixelart, where people who lived through it kind of get it, and are happy to have their childhood nostalgia weaponised, whilst others are drawn to it despite never having had it. I put this idea to Gilbert.

‘Yeah, I look at nostalgia as it kind of operates on two levels. There’s the people who lived through the period who are nostalgic for the period, then there’s this other group of people who didn’t live through the period but they wish they had in a way.’

‘I don’t know if you’ve seen Stranger Things but that’s a really good example. I kind of lived through that, I was those kids, but there’s lots of people who weren’t alive in the 80s and still are kind of nostalgic for that period.’ He separated the decades on the table, slicing through them with his hands. ‘I remember when I was a kid we watched Happy Days and American Graffiti was a big movie, and these were all things about the 50s. I think there’s a little bit of that — I’m sure there’s a lot of that — with Thimbleweed Park.’

The game has had a hard time shaking off the idea that it’s intentionally a throwback or retro, which can be read as ‘bad on purpose’. I have had long, frustrating conversations about it with a friend, wherein he says something like ‘I think I’m just 20 years too young for this game’ and I say ‘This game isn’t 20 years old, how do you not understand?‘ Yes, the industry in general is better at making games, and that does not exclude the Thimbleweed Park team.

‘We’ve just become better game designers over the years. Even things we were doing back on Monkey Island, I kind of look back on it and go “Yeah we probably shouldn’t have done that. That was probably not a good design choice,”‘ said Gilbert, quietly looking back over his own shoulder. ‘I think the game is just better designed in a lot of ways.’

‘I’m very, very happy with it. You always feel very scared, because we send out press preview copes — that’s a horribly terrifying moment for me. Like “Oh my god, what if everyone hates it?” But I’m very happy with the game. I would love to build another point and click game. I hope this is successful enough that it says “Yeah, there is a market out there for that stuff.”‘

/https://oimg.videogamer.com/images/02a8/7dcd8930-3288-4fcd-81d0-4c61e336fd56_HotelRoom.png)