You can trust VideoGamer. Our team of gaming experts spend hours testing and reviewing the latest games, to ensure you're reading the most comprehensive guide possible. Rest assured, all imagery and advice is unique and original. Check out how we test and review games here

Each month, we invite élite art critic Braithwaite Merriweather to appraise the box art of the latest game releases. In between his time spent wandering the corridors of culture, Merriweather writes on a freelance basis for various publications, including Snitters and Nuneaton à la Carte. If you are unaware of his prowess, rest assured; he’s on a crusade to educate the unwashed. Put simply, he’s a man that needs no introduction.

Friends! I write to you from the Hebrides. I may well be accused of being Scrooge, but I can’t bear the crush of Christmas—the nieces and nephews, endlessly spawning like frogs; the fools that comprise my family; the crackers; the incessant questions, like “have you managed to get your work into any exhibitions?” The cretins that make up the Merriweather clan can’t seem to appreciate the service I provide to the masses in the form of my box art criticism. They can’t see that I am at the vanguard of a new medium—a medium that needs a voice, that craves an arbiter of taste! Anyway, enough of all that. I have rented myself a getaway cottage, for the entirety of December, in the embrace of the North. I lurk just off the cold shoulder of the land. And we shall have none of that festive nonsense. Shut the door, close the curtains, and settle in; we shall, as ever, retreat to the work!

Wattam

Watching these little creatures caper and jig is an outrageous feast for the senses; it bears the curious cruelty of reminding me of childhood frollickery while also bringing to mind the atrocities committed by children when it comes to art—those garish splodges that you find pinned to fridges, while expectant mothers beam and beg for praise. I am sometimes asked if these juvenile attempts at painting might be forgivable, considering the age of the artists. My response is always the same: No. My reason is simple: the art I was deigning my mother fit to receive when I was at the tender end of the human coil was good enough to adorn even college-age collections (though try telling that to the Wimbledon College of Arts, to which I sent several samples of my childhood works only last year, and from which I received only bureaucratic vagaries—morons).

Nonetheless, among the many virtues of this “Wattam” is the way it jolts life into the inanimate elements of what would appear to be a picnic; this jamboree of smiling mischief calls to mind “Still Life: Fruits and Pitcher” (1939) by Picasso. Consider the shadows beneath the fruit, like little black shoes; one imagines them mincing to and fro in Picasso’s mind. Then, there is the jug, which appears to have grown a large eye. What Picasso suggests, and what this “Wattam” seems to enjoin, albeit rather more playfully, is the idea that the human beast is made so by way of its civilising virtues—the freshly picked fruit, the picnics in the park, the bright balloons of a summer’s dalliance—and that these objects might take on and reflect such civilisation. Hence, in “Wattam,” the green vegetable cube with the bowler hat. But what lies underneath the hat? A bomb! As if the delicate order is ripe to explode at any moment.

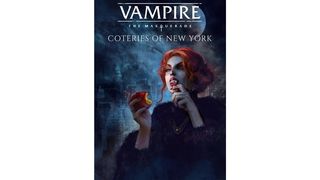

Vampire: The Masquerade—Coteries of New York

As a rule, I have trained myself to be wary of long titles. Ever since Salvador Dalí attempted to cloak his empty colour-bluster with names like “Dream Caused By The Flight Of A Bee Around A Pomegranate A Second Before Awakening” and “Declaration Of The Independence Of The Imagination And Of The Rights Of Man To His Own Madness,” I’ve always harboured a healthy suspicion of overgrown words. As such, you can imagine my hesitance when being confronted by “Vampire: The Masquerade – Coteries of New York,” which seems to indicate that the artist couldn’t decide between three titles, so opted to fuse them with punctuation. As it happens, the work itself is pleasingly simple. It shows a red-haired vampire woman whose lips drip blood despite, rather confusingly, her taking a bite from an apple. Behind her lies the night.

Edvard Munch, in 1895, depicted a similar subject in his painting Vampire (Munch was less of a ditherer, and thus was able to pick a single title that summed up his aims succinctly). We might even imagine this woman being the subject of both works, biting the neck of some poor sap and draining him dry (I know how the poor bastard feels), before jumping a century or so forwards to New York. I am a sucker for a work in thrall to the past, but only when such enthrallings betray a respect for—even a playful ribbing of—the masters. This “Vampire: The Masquerade—Coteries of New York” achieves this, for the most part. My only reservation is that title, which is a masquerade all right: as something far more grand and puffed-up than it actually is, a crime which, in fairness all vampires, especially Dracula, are unreservedly guilty of.

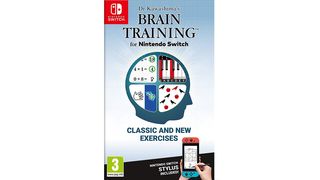

Dr Kawashima’s Brain Training

“Dr Kawashima’s Brain Training.” The name sounds like a type of torture—a knowingly benevolent-sounding method for extracting crucial information from the minds of one’s enemies. (I am fairly certain that my ex-wife was a devotee of such techniques.) The work itself is, thankfully, far less tortuous than one might assume. I am reminded of Dalí for the second time this month, in this case due to the strange inclusion of text lines next to the more abstract visuals. We gaze upon a human head, in which the chambers of thought and mind are devised and divided into four. All this seems to be backgrounded by graph paper, invoking surreal flights of school maths lessons (a unique method of torture indeed, for the young, visionary artist). The scholastic theme rings throughout: within the quadrants are images of maths and music, mingling with depictions of play.

This work invokes Jean-Michel Basquiat, in particular his painting “Untitled” (1981), which depicts a similarly divided head. I have always felt a deep kinship with this image—suffering with such beauty locked away in my mind, misunderstood by so many, especially those at the Sheffield Institute of Arts Gallery. What “Dr Kawashima’s Brain Training” achieves is it dips its toe in the waters of more grounded surrealism—“The Son of Man” (1946), by Rene Magritte, for instance, which obscures its subject’s face with an apple (“Wattam” continues to haunt us!). But something about this head feels, despite its crowded quarters, absent. One senses a lingering irony stitched into the canvas: the notion that there might not be a brain to train, that obsessive formal training might fill one’s mind and actually block out any room for creativity. I wonder if the artist behind this work has also had priors at the Sheffield Institute of Arts Gallery, and is reaching out to us.