You can trust VideoGamer. Our team of gaming experts spend hours testing and reviewing the latest games, to ensure you're reading the most comprehensive guide possible. Rest assured, all imagery and advice is unique and original. Check out how we test and review games here

The season is almost upon us, and you’ve nothing to fear. Unlike the cramp of Christmas, which shuts you in with dreaded relatives, or the withering spotlight of a birthday, under which you must be seen not to wilt, Halloween demands a hermitage. Drawn curtains, snuffed lights, banished acquaintances, and food marinated in caramel: is there any better holiday? But it has to be matched by a video game menu of careful choosing. Here I present a list of unsung horror games perfect for the occasion – and all available for cheap!

White Night

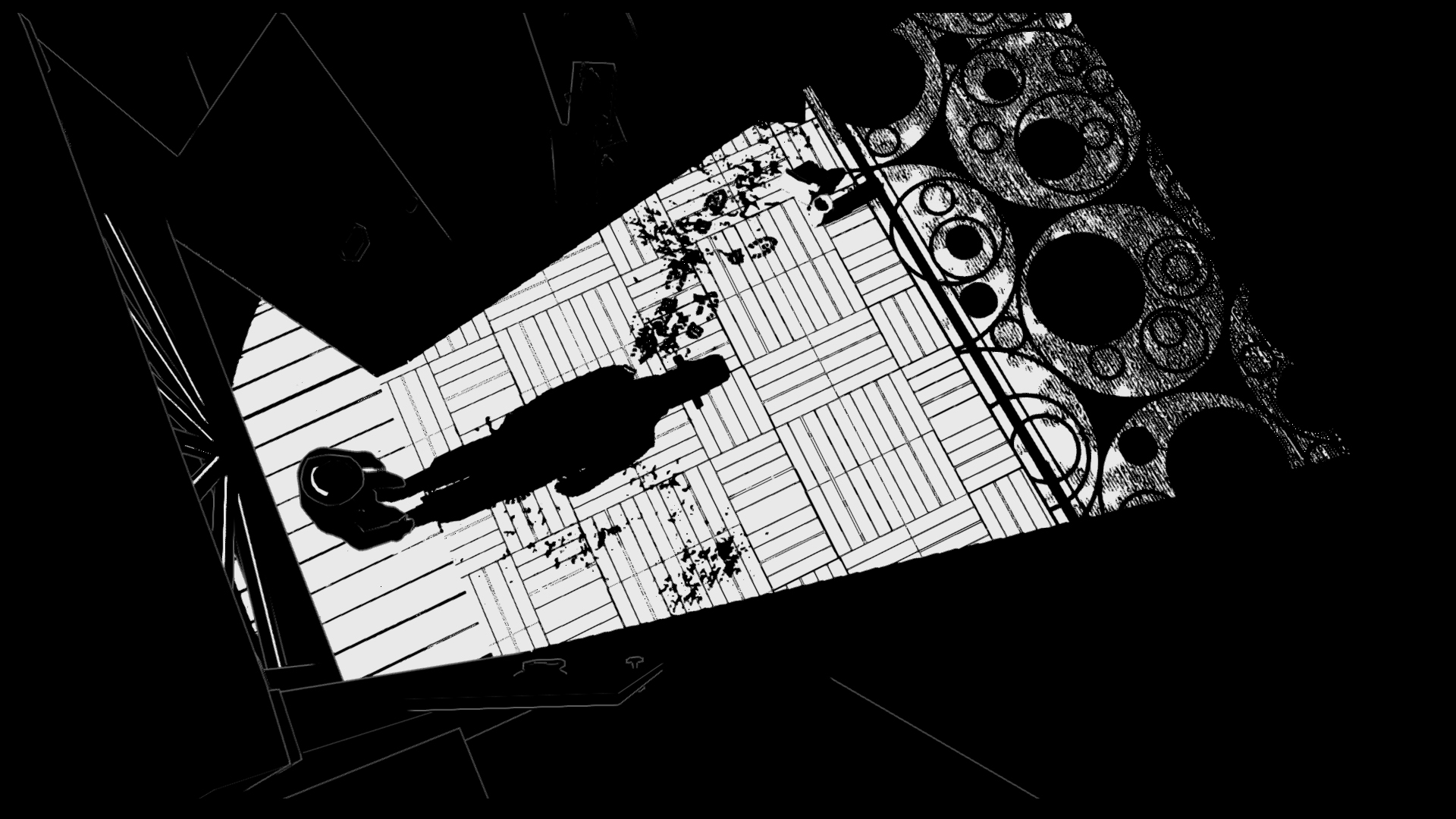

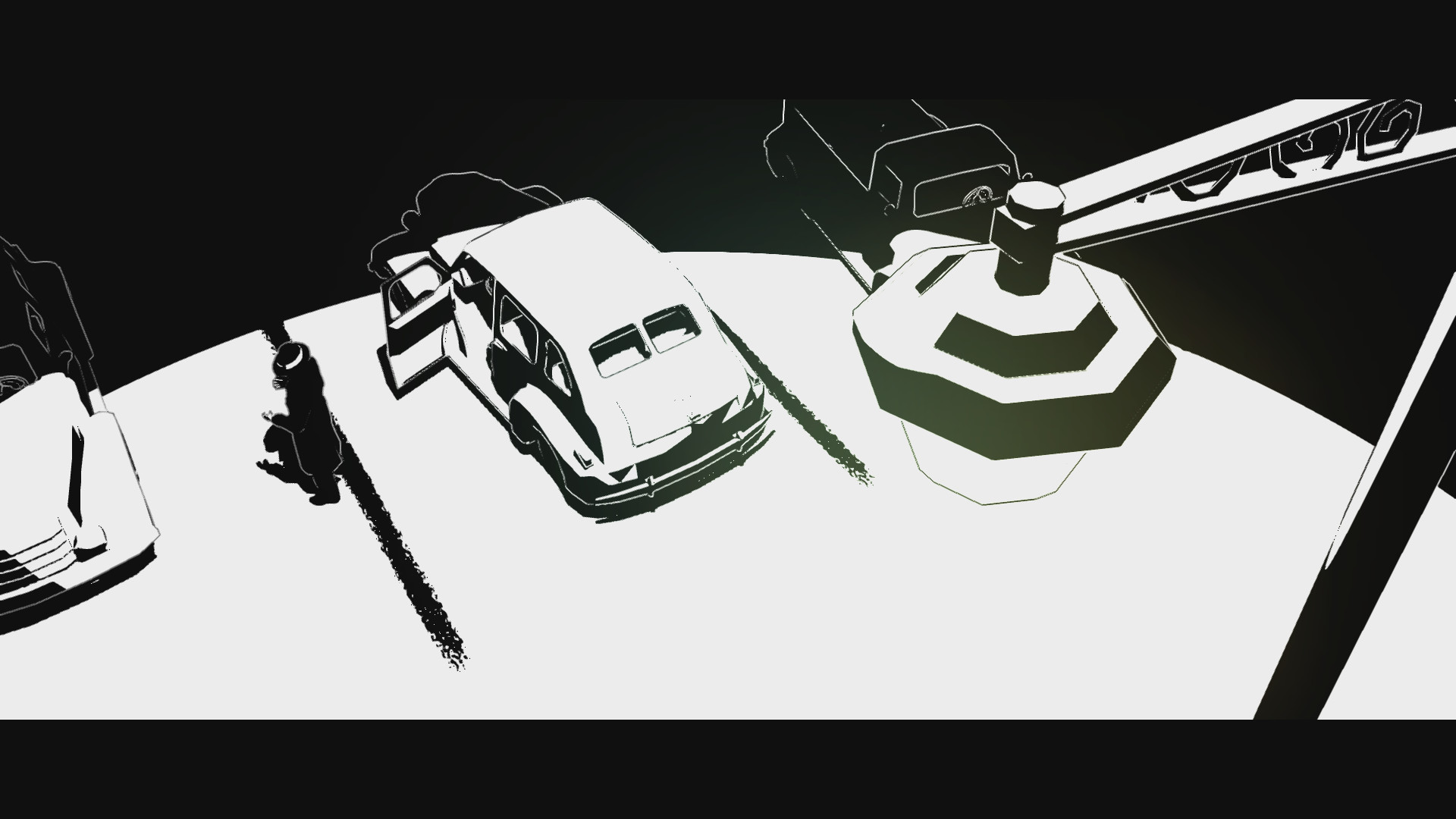

The folks at OSome Studio must like a drink. So draining is a dry life that White Night's Prohibition-era Boston is presented in stark black-and-white. Alcohol is colour; I’m with them. Your character, who limps from the crumpled wreck of his car to a nearby house, tumbles into a nightmare of static camera angles and improbably baroque puzzles. But for us, raised on Resident Evil, it’s a dream.

It’s best touch is its style. The night sky is paper-white, with a moon the colour of coal. The shadows fall on your character’s face like splotches of spilt ink; it resembles a Rorshache test, which is a neat approach to the blank slate protagonist – what do you see? Looking at it, you won’t find a single shade of grey. Its plot, meanwhile, is full of it. A fog of dark history encircles the house at its heart, and the puzzling mist of its characters hangs thick in the air.

The other game that bore a similar true black-and-white look was PlatinumGames’ MadWorld, but it wasn’t as pure; it was prone to pressurized gouts of red, and its whites were more the worn cream of comic books. White Night, on the other hand, allows only the tiniest glints of colour – the yellow of a lit match, or the pale green of a ghost. It does right by its style, too: wafting it, like a white sheet, over the creaking furniture of survival horror, draping its dreary parts with fresh fear.

Haunting Ground

A girl is trapped in a castle. The castle is full of monsters. The girl meets a dog. The dog fights the monsters. And the girl wears an ill-advised miniskirt. Such is the setup for Haunting Ground, or to give it its sober Japanese title, Demento. Oh what I wouldn’t give to be a fly on the wall – or a bat in the rafters – of a Capcom pitch meeting.

The girl is Fiona Belli, an 18-year-old college student, and the dog, a White Shepherd, is Hewie. A car accident has stranded Fiona in a castle caught somewhere between Disney and Dracula. We’ve got homonculi, philosopher’s stones, evil alchemists, and puddles of blood; if only we had talking candlesticks, then you might expect a musical number. If Resident Evil cribs from the likes of Romero and Raimi, Haunting Ground takes notes from Polanski and Argento – the masters of weird.

Fiona moves, as many of her Capcom contemporaries do, like a tank, and her spirit is similarly fortified. Though she can’t defend herself, Hewie will growl away the ghouls. And while one eye needs to be kept on her sanity meter, it’s you the game goes after. In the years since I first played the game, I’ve not been able to shake some of the more disturbing sights and sounds. The Japanese title rings true: you’ll come away with a brain full of demented mementos.

Nosferatu: Wrath of Malachi

A different castle, a different time, a similar menace welling up from the gloom. The sort of people that will tell you about Nosferatu: Wrath of Malachi are the same sort that will tell you about Murnau’s film – as pale as the count, similarly shut up in dark rooms, and doomed to a half-existence of rising late in the day to creep around in the early hours. People like me. Wrath of Malachi is a first-person shooter, an adventure game, and a horror game, but more importantly it’s a restoration job. It gives fear back to vampires.

The game sees a character called James Patterson (presumably peeling himself from writing his latest detective thriller) travel to Romania and fend off his sister’s fiancé, who is interested not in her hand but her neck in marriage. Developed by Idol FX, Wrath of Malachi is a lesson in the plucky and the makeshift. If you’re lacking in the graphics department, then cake the cracks with a soft-grain filter and pretend that’s totally what you were going for.

It works, too. Despite the baroque charm of Patterson’s flintlock pistol and silver cane sword (!), the game keeps you on edge. Each corridor is so sooty with darkness it requires not walking but wading through. And though you’ll spend time between key quests blasting the undead, you’ll still shiver at the things you see. Take the knife-fingered count, for example: ravenous with ratty fangs and a head like a full moon, he draws fear as well as blood, which has given the game, first released in 2003, an unnaturally long life.

The Thing

John Carpenter gave his blessing to The Thing. He leant his voice to The Thing. He considers it the canonical sequel to his film, The Thing. And that’s the thing: if you’re making a movie tie-in game, tie it in; don’t cram it in, scuffing the edges of a second-hand story. The best games to bear the brunt of a movie licence are the ones that sidle up alongside with fresh anecdotes, as deferent as dinner guests. Think of Alien: Isolation, of The Warriors, and, if you haven’t already, think of The Thing.

Taking place after the film, it sees two Special Forces teams dispatched to Antarctica to investigate the devastation brought about by Kurt Russell’s mullet. At first, the creature dug up from the ice is nowhere to be seen, but its malice has metastisised. The game is run through with the same veins as the film: those that pulse with paranoia. As you explore the arctic base, your interactions with soldiers are frosty; the mood is one of fear in deep freeze that might thaw at any moment, leaving blood behind.

Play is codified with card keys, downed generators, and blood test kits. Its brand of third-person shooting might be frozen stiff by today’s standards, but it’s the tension, tight as a drum, in the quiet moments that still holds power. For people like me, whose lives are measured out in the plastic movie cases of CEX, the game feels like a special feature buried deep in a DVD menu. Ripe for digging up from the ice.

White Night

- Platform(s): Linux, macOS, PC, PlayStation 4, Xbox One

- Genre(s): Action, Adventure, Survival Horror