You can trust VideoGamer. Our team of gaming experts spend hours testing and reviewing the latest games, to ensure you're reading the most comprehensive guide possible. Rest assured, all imagery and advice is unique and original. Check out how we test and review games here

Caution: This article contains vague spoilers for the games Dear Esther, Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture, The Stanley Parable, Firewatch, Her Story, and even vaguer ones for Virginia and The Bunker (also for a book called The Gone Away World by Nick Harkaway)

Unreliability is a beautiful thing. The first time I played Dear Esther I only managed to trigger the opening bit of narration before my house (which at the time was in a village isolated enough that we couldn’t receive broadband internet – the ignominy!) suffered a powercut. I had to try again the next day, and got an opening bit of narration that was entirely different to what it had been the day before. I was confused, and also incredibly intrigued, like waking up with a hangover inside your flat but finding your keys on the doorstep. The mystery compels us to solve it.

Recent weeks have been a rich time for the ‘walking simulator’, with the release of both The Bunker and Virginia, and Firewatch and Dear Esther (darlings of earlier this year and 2012 respectively) coming to new platforms. Though that term may have started off as a condescending one, as more of them appeared ‘walking simulator’ became an acceptable way way to describe them. They clearly have enough of an audience that discussing whether or not they are games is moot. The people who like them, of which I am one, tend to really like them. What is it about them that captures us, despite the complaints they’re too short, too empty, not engaging enough? I submit that a large part is the sticky web of unreliability.

When we, the idiot squishy mammals, consume media we tend to assume things like narrators are telling the truth, and therefore guiding us without bias or prejudice through the story, whatever it may be – at least, until it turns out they’re not. We might say we like clarity and steadfastness and closure, but things that stick with us don’t always have that. Look at Fight Club and American Psycho, for example, both stories where the narrator is revealed to have had only a tenuous grasp on reality the entire time, and both stories that regularly crop up on people’s Top Ten Best Ever Movies to Impress My Friends When I Talk About Them With Deep Insight list. In Lolita, Humbert Humbert tells his story while angling it to convince you that he’s totally an alright dude despite the fact he likes little girls, which categorises him as definitely not an alright dude under any circumstances. One of my favourite books is The Gone Away World, in which it turns out the narrator has not been quite who he thought he was for his entire life. It’s heartbreaking, and very effective, and games are mining that too.

/https://oimg.videogamer.com/images/95e9/rapture_3.jpg)

It’s not that walking simulators are the first to use that kind of technique – a bunch of RPGs retcon bits of lore that appear in, for example, incidental books by declaring in-game historians as unreliable hacks unfit to appear on Time Team – but these games use it so often that it’s a trope of the genre. They may not be able to channel in through an unreliable narrator specifically (some of them, for example, don’t actually have what we’d think of as narration) but they all obscure the truth and deliberately offer unreliable information to the player to alter their experience and move expectations around.

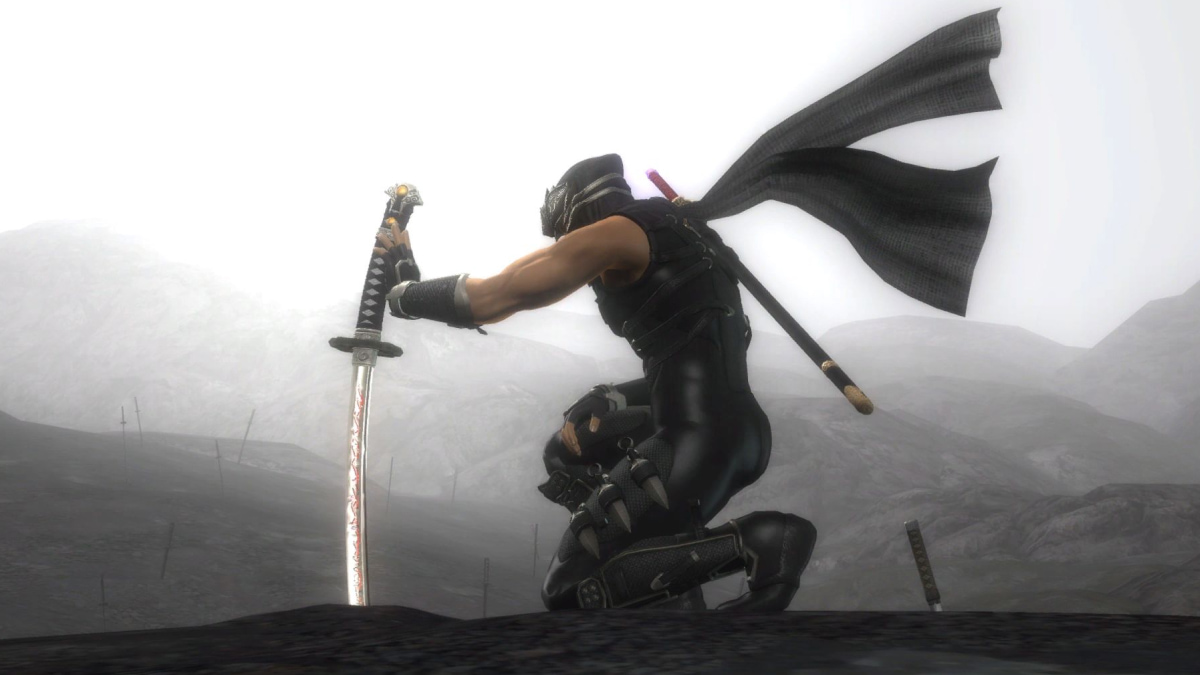

Dear Esther was first commercially released in 2012. It’s a ghost story, or maybe it isn’t, where you explore a blasted, desolate island in the Hebrides, occasionally triggering a voiceover that reads snippets of letters to Esther. There’s no fail state, and no direct interaction with the world. The narrator explored the island before you, using and frequently quoting a book by a man named Donnelly who had himself charted part of it some hundreds of years previously. It later becomes apparent that Donnelly was addicted to laudanum and ravaged by the most topical sexually transmitted infection of that century, and that much of his book may be therefore characterised as ‘syphilitic ravings’. At the same time, the narrator contracts a more regular infection after breaking his leg. He becomes less lucid with each moment, and conflates himself and various other people who have lived on the island. An unreliable narrator wrapped up in an unreliable narrator. And the game was specifically designed so that you can never truly know what happened.

The Chinese Room, the devs behind Dear Esther (which originally started life a Half Life 2 mod almost a decade ago) have re-released it with some optional director’s commentary, which you can access as you reach different parts of the island. In it the creative director of The Chinese Room, Dan Pinchbeck, says you can play the entire game and “might not understand what happened,” that in the narrator’s sections “it doesn’t matter the sense it made”, and that it feels more like “the dream of an island”. Indeed, one of the theories is that the island in Dear Esther is entirely imaginary. At the points where you can trigger voiceover there are three or four different scripts, so every play through is a slightly different experience. Robert Briscoe, the artist for the game, made it so that many of the environmental objects (old papers, books, photographs) are randomised as well. In an archived blog post Pinchbeck shared some notes he made for the translators localising the game, most of which are asking them to keep in all the odd grammar and not try to make it make actual sense.The island, and it’s story, are deliberately unknowable.

The Chinese Room followed up with Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture, where you explore a fictional village whose inhabitants have all mysteriously disappeared, and left nothing but glowing lights and fragments of old conversations and memories, sometimes from years before. There has evidently been some kind of apocalyptic event, but who you are, and what exactly happened, remains up for debate. The memories you can piece together are all from the villagers, who often lie, contradict themselves, or else suffer huge changes in perspective that mean their testimonies can be called into question.

/https://oimg.videogamer.com/images/2774/virginia_4png.jpg)

It’s the same for all the walking simulators I can think of. The Stanley Parable has a narrator who can become so unreliable that he’s actually hostile to the player. The ending of The Vanishing of Ethan Carter changes everything you’d been told about the game to that point. Gone Home is clever as f*** and tricks you into thinking it’s one thing when really it’s something else entirely. In Virginia, which has only been out a few days, there’s no dialogue whatsoever: you rely on how you understand the imagery, which is peppered with the interpretive dreams and hallucinations of the character you play as, and large chunks of the continuity are missing. The Bunker is filtered through the perceptions of a man who has lived underground his whole life and has increasingly frequent visions of his dead mother. In Firewatch you’re guided by a woman you never see, who never reveals the whole truth about herself, and leaves before you meet her. In Her Story there might one suspect, then two, then one again, depending on which videos you uncover. The list goes on.

Often in games we’re told a thing is the case, and so it turns out to be. In some cases you don’t even really need to pay attention, you just go and do – which is fine! I really like World of Warcraft, and I don’t need to know what relevance a dozen mushrooms have to the lore to go and collect them. Maybe the guy who asked me just really likes mushrooms? I don’t know, but he’ll give me some new boots either way, so whatever. When you simplify gameplay down to a few hours of vaguely-guided exploration you have to get creative in how you tell the story, or nobody will give a s***. If you get creative enough they’ll give a s*** for way longer than they would otherwise.

These games don’t tell you everything you want to know, and even lie to you. You have to actively think about them afterwards if you want to pull a conclusion together. These are the games that produce the heated conversations, that make people replay them over and over again to try and find something they missed, cross referencing with others, posting transcriptions on Reddit and applying frequency ciphers and morse code to number sequences. You’re not collecting mushrooms in exchange for new boots because you don’t know whose feet they are. You might not be a hundred per cent that you even have feet. It’s great because that’s life! I don’t mean the feet thing, specifically, although that’s probably a recurring dream some of you have. I mean that life is uncertain, and unreliable, and you can’t be sure of people. And sometimes I want games to give me that certainty. But other times I want them to tell me a lie.