You can trust VideoGamer. Our team of gaming experts spend hours testing and reviewing the latest games, to ensure you're reading the most comprehensive guide possible. Rest assured, all imagery and advice is unique and original. Check out how we test and review games here

Each month, we invite élite art critic Braithwaite Merriweather to appraise the box art of the latest game releases. In between his time spent wandering the corridors of culture, Merriweather writes on a freelance basis for various publications, including Snitters and Nuneaton à la Carte. If you are unaware of his prowess, rest assured; he’s on a crusade to educate the unwashed. Put simply, he’s a man that needs no introduction.

Hello friends! I find myself thrown back on plush waves of nostalgia, adrift on a sea of memory. I dream of galleries! Of those thuggish security guards in The Courtauld Gallery—times are clearly tough that I should look fondly back on those neanderthals with even the faintest fog of pleasant feeling. I miss my improvised pavement galleries, set up on a fanciful whim, to inspire the public, to jolt them from their opioid stupor and energise their minds! I miss those long, lounging days spent on the South Bank, in the summer company of swooning tourists outside the Tate—their blank faces as I beckoned them over, in order to tell them why the latest Tracy Emin installation is best avoided.

But, in an attempt to cheer myself, and, perhaps, to offer some spirit-sprucing sentiment, there are some things I don’t miss. The London Underground, for instance, in which the juice of humanity is jostled and drained out onto the tracks, and we wind up with carriagefuls of rasping wraiths, who reach their destinations in a state of depravity, ravenous for any reminder that they started their journeys in a state resembling the civilised. Further to that: having to converse with my local council (on matters such as my improvised pavement galleries), and thus to be reminded that the glue of government—that which holds societies together—resembles real glue: thick, oozing employees whose stupidity seems to stick to everything around it. Then, of course, there is my ex-wife: the attorney-powered banshee who sought to claw the clothes from my back. There’s no missing that!

Star Wars Episode I: Racer

I believe this venerable website—to which I file my humble copy like an artilleryman would heave a noble iron ball into the shadowy snout of a canon, to be launched into battlefields of art critique—is attempting to provide me with good cheer. This first work, entitled (somewhat bewilderingly) “Star Wars Episode I: Racer,” is an escape, a call to adventure, an exaltation of the spirit. In our current collective situation, the idea of movement, let alone the brand of boyish, toyish high speed that abounds in this work, is one that gathers rust with each passing day. How sweet to feel the sucrose rush of not only maximum-velocity frivolity but of reverence—reverence for the moments in which art and vehicles have met and melted.

I am thinking, of course, of Vettriano’s “Bluebird at Bonneville” (1996), in which a car that looks part-shark is doted on by a gaggle of hatted bystanders, whose shirts are the same shade of blinding white as the surrounding desert sand. But so, too, am I reminded of the Art Cars of BMW—in particular, of Alexander Calder’s “3.0 CSL” (1975) and of Roy Lichtenstein’s “320” (1977). I like to imagine that these artists, when approached by the German giant, imagined what might happen to their paints and their passions when roaring along at a hundred miles per hour. I once tried something similar when my father took us on a family outing to Brands Hatch. I attempted to adorn the bonnets of the racers with the freshly hatched designs of my own brand, and was stopped by security personnel. It was a day that forever changed me: the first time I was confronted with the full force of the philistines, long before I learned that they weren’t roadblocks; they were ramps!

Maneater

This work, entitled “Maneater,” seems to be a bold refuting of Damien Hirst, and I’m always game for a refuting of Damien Hirst, bold or otherwise. Hirst’s “The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living,” (1991) for which he had a tiger shark fished up off the coast of Queensland, soused in formaldehyde, and set in a glass box, remains the saddest excuse for art I’ve seen. The poor beast, a vision of frozen fury, crumbling with each passing hour into the acid that surrounds it—it’s a situation with which I am profoundly familiar, having been married to my now ex-wife for some years. The artist behind this work clearly means to subvert Hirst’s banal message, and does so with explosive brio.

Look at this poor fellow, upside down and airborne amidst a frothing flood of death incarnate (those on the admissions board at St Martin’s College will know the feeling well), and about to be devoured by the manifestation of nature’s indifferent fury. It could almost be called “The Physical Certainty of Death in the Vicinity of a Shark Willing to Breach the Water with the Express Purpose of Dismembering You.” Of course, that would be too long a title, and the game box would need to be configured in a landscape format in order to facilitate that. Greeting this work—whose swaggering thrust is directed at the jugular of another—on its own terms, I find little to rave about. A mildly pleasing swath of blue, as sea, smoke, and sky girdle the central blast—nothing to write home about (although clearly I currently am).

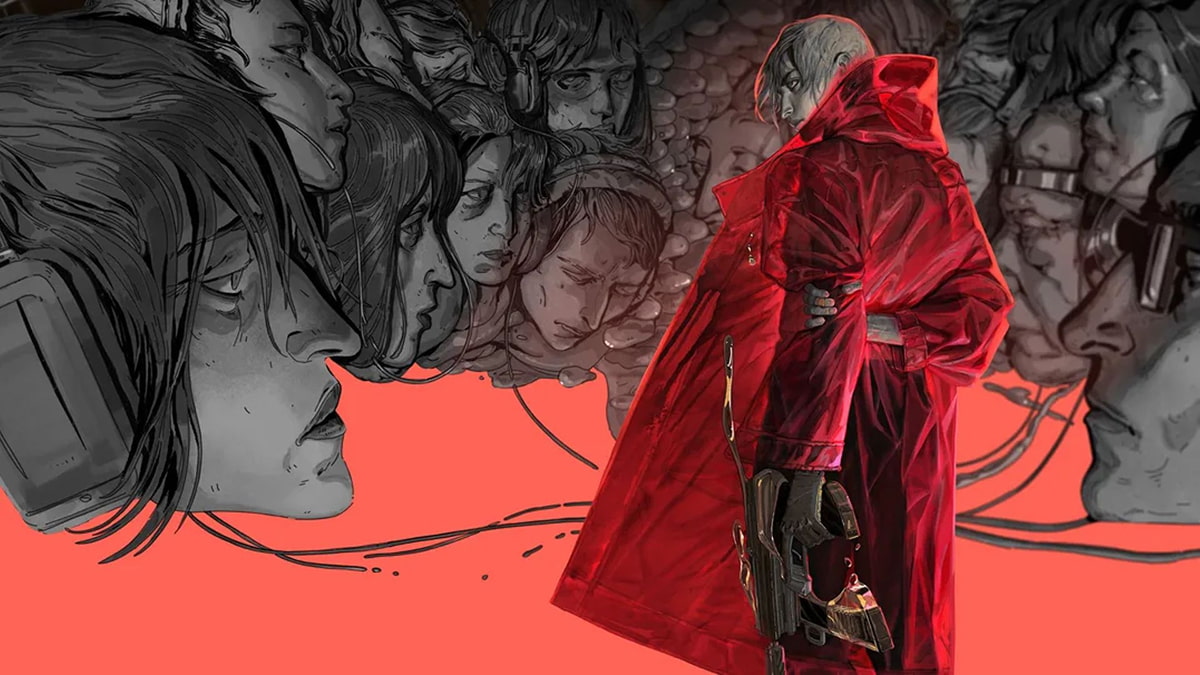

John Wick Hex

This curious work seems to be a pastiche of “The Son of Man” (1964), by René Magritte. Only, where Magritte blocked off his subject’s face with a green apple that hung in the air, the artist behind this word, entitled “John Wick Hex,” has chopped his subject’s head in half with the top of the frame. What’s more, Magritte’s sensible suited gentleman and soft colours have been replaced by a gun-toting fellow, equally smartly dressed, and a wash of delirious purples and pinks. Perhaps a more tongue-in-cheek title would have been “The Gun of Man.” In any case, this “John Wick Hex” doesn’t leave much of an impression; looking at its lurid hues produces the feeling of mild hangover—now there’s one thing that I don’t miss: staring dumbly into the daylight, trying to shake the headachey hex of the night before.