You can trust VideoGamer. Our team of gaming experts spend hours testing and reviewing the latest games, to ensure you're reading the most comprehensive guide possible. Rest assured, all imagery and advice is unique and original. Check out how we test and review games here

Thirteen years on from its original release, Crysis, the game that melted a million GPUs, is back. Playing it over the weekend, in the form of Crysis Remastered, I was relieved to hear my PlayStation 4 break into a heavy-breathing fluster. I like to think that it sensed the sheer gravity of the graphical situation and fired up its fans in a show of respect. Then again, this new version boasts, according to its website, “8K high quality textures, HDR support, temporary anti-aliasing,” and “improved art assets,” so maybe the machine was being given an honest, vent-melting workout.

But is it worth it? There is a moment, early on in the action, where we’re shown why we might endure the tropical jet streams wafting up from our coffee tables. Emerging from a damp clearing, you crest a rocky outcrop, and take in developer Crytek’s creation: a blinding white beach, lapped by azure waters and dotted with deferential palms. It looks like the setting of a perfume advert, gilded with a Photoshopped shine, and you can imagine models in low-slung jeans rolling in the surf: “Crysis, by Calvin Klein—render your obsession.” I never played it in 2007, lacking the requisite hardware and financial heft. As such, I can’t vouch for the degree to which its sights have been shined and mined anew. However, I can report that it looks extremely handsome. It offers up the kind of postcard vistas—prized by haughty high-end PC owners—that made console players green with Nvidia envy.

Starting it up for the first time and hearing a woman declare, in magisterial tone, “Achieved with CryEngine,” I felt as if I’d gained entry to a private club. Of course, in what feels like tradition, I’m still barred from the VIP section. Even now, I can’t run the game to its fully fuelled potential; my base model PS4, unlike the Pro, deprives the remaster of ray tracing. So close! Still, you don’t need ray tracing to see Crysis in a new light. All you need is time: that which has whipped by and weathered its visual impact, and a further pool of pleasant hours in which to enjoy those thrills that remain untouched. The question, for those venturing into its jungles in a virginal state, is, “What is Crysis?” What hunk of game awaits those willing to hack through the steamy foliage of technology? In short, CryEngine or not, what has been achieved?

The story begins last month. A subtitle reads, “Lingshan Islands, Phillippines Sea—August 14th, 2020.” We open with a group of fidgety guys, wrapped in rubbery performance gear, surrounded by the silvery comforts of near-future technology, and lumped with names like Prophet, Psycho, Nomad, Jester, and Aztec. All of which, presumably, describes elite players of Crysis, loitering restlessly in a matchmaking lobby. But these grunts are not playing. Sent by some shadowy corridor of the U.S. government, they cruise through gloomy skies, ready to plummet to the rescue of a kidnapped scientist. (There’s more than a hint of Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater, in the setup.)

What follows is a strange, jumbled experience. The Korean People’s Army is occupying the islands, and thoroughly cramping their style. Their rich natural beauty is ruffled by barreling jeeps, and the crisp air above is buzzed by choppers. Checkpoints are set up in ramshackle fashion, all rusted iron and plywood, and they are as destructible as the plot. I can just about sketch you the premise, but not much more. Most of the dialogue is drowned out by a crashing orchestral score—a series of thuds and boring chords—and as soon as the flying alien robot squids showed up I checked out completely. Being given the job of writing Crysis—the fate that befell Martin Lancaster, Tim Partlett, and Greg Sarjeant—of cajoling its jarring elements and images into a narrative, must have been like trying to pin a troupe of addled improv artists to a script half-way through a live performance.

Imagine trying to muster a reason for the squids’ nasty habit of leaving an icy trail in their wake, as if leaking liquid nitrogen. The fact is that the reason was to show off the environmental effects of CryEngine 2, and, seeing the grass turn a light, flash-frosted blue, with vapours rising off its blades, it seems as good a reason as any. There are scenes, elsewhere, in which all urgency is numbed and frozen by the touch of the underlying tech. Take, for example, the sequence that sees your commanding officer hoisted skywards and spirited into the trees. It might have been more dramatic, if my eyes weren’t drawn to the noonday glare, which was needling through the canopy with glorious fidelity—far more gripping drama than anything thrown up by the plot. When it comes to the state of the art, the art in question is seldom storytelling. In the case of Crysis, the problem with attempting to peel back its technological powers and examine its essential substance is that one is melded, like a fried motherboard, to the other.

But this is no bad thing. Complaining that Crysis is less a video game than a tech demo is like rolling up to a Jackie Chan movie and decrying its reliance on physicality. To do so, in either case, is to miss the point: not only that there is joy to be had—in a blizzard of blurry fists as in a lizard-green hillside—but that such joy can shape our feeling for a work as strongly as any other method. Here, the prevailing sensation is that of being taken for a test drive—of being goaded, by a crazed car salesman, into pressing your foot down and devouring the miles.

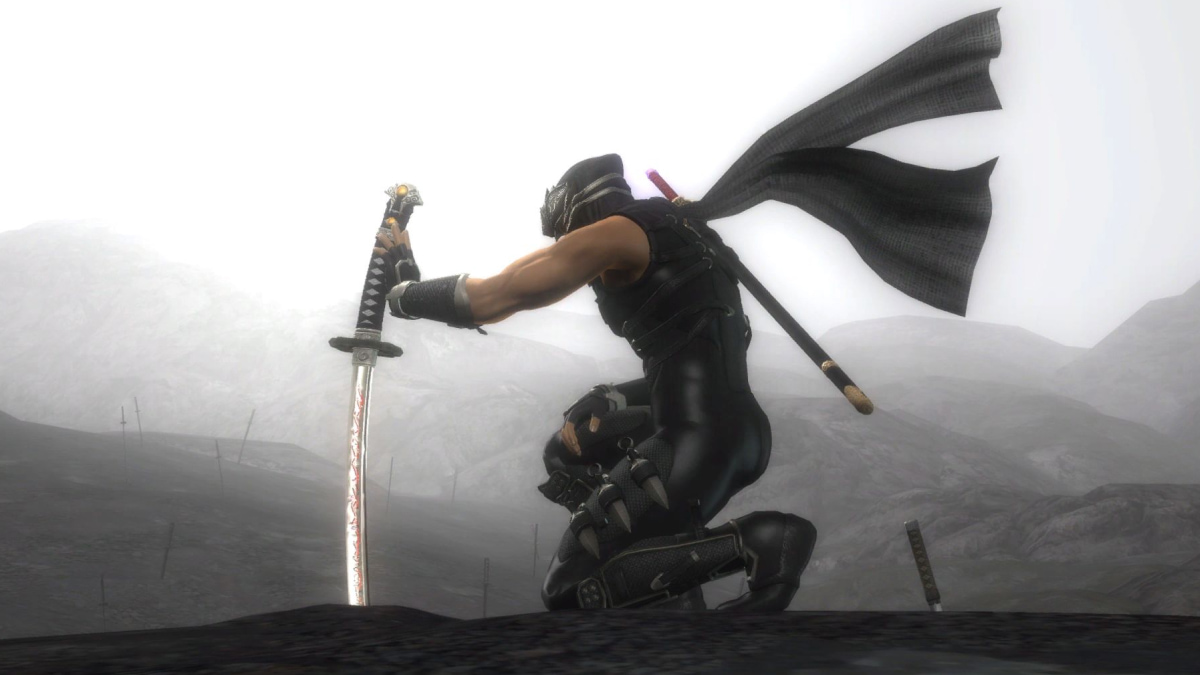

If you want to taste freedom this year in games, I thoroughly recommend you spend an hour or two in Lingshan. If you do, you’ll find your approach prodded by the firepower of the engine more than that which is wielded by our hero. He wears a Nanosuit—a fibrous exoskeleton that massages his muscles, steels his skin against approaching bullets, and bends light around him in a bulging shimmer, like the villain of Predator. It’s all very cool, but, I have to say, I was beckoned to unleash my inner Arnie not because of any futuristic gizmos but because of the way that the treeline reacted to a roaring machine gun. My foes, crouched in the brush, were showered with freshly mowed roughage, before they were mulched by my assault rifle. Likewise, it wasn’t my turbocharged sprint or my spring-heeled leap that gave me the itch to explore; it was when I realised that the draw distance wasn’t so much a brag as a dare.

That’s the best reason to play Crysis Remastered: its sandbox, which is unspoiled by climbable towers, and which refuses to snarl you up in skill trees. After ten minutes, it hits you how much you’ve missed that purity, how rarely it comes around, and you realise that this is the real sequel to Far Cry—faithful not only to its liberating vision but to its surreal mood. That game, made by Crytek and published by Ubisoft, was a showcase for CryEngine 1, but the obscene splendour of its graphics gave way to something elusive. Its shores were crashed by the same dreamy discomfort that Danny Boyle tapped into with The Beach: that brain-fazing mix of the serene and the ugly, like blood soaking into sugar. That same blend is here in the dark-edged Eden of Crysis, a reminder of paradise lost.

Crysis Remastered

- Platform(s): Nintendo Switch, PC, PlayStation 4, Xbox One

- Genre(s): Action, Adventure, Shooter