Video Gamer is reader-supported. When you buy through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Prices subject to change. Learn more

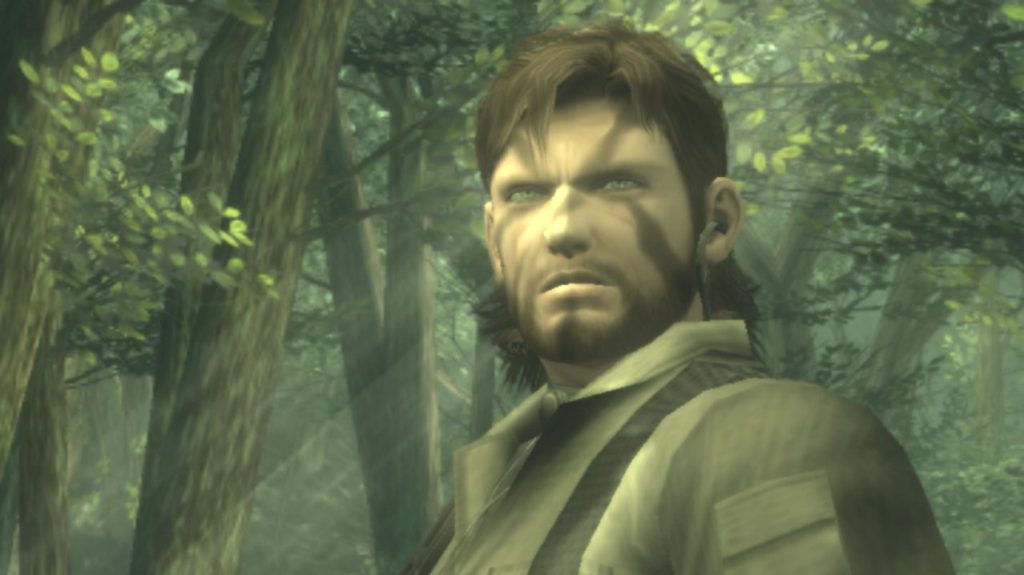

The best Hideo Kojima game I’ve played this year came out in 2004, and it was set 40 years before that. Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater, which is 15 years old today, is a game about time. Its characters are like rocks in a riverbed, bearing the surge of years. “People and their countries are both changed by the environment. And by the times,” says Eva, the game’s femme fatale. This temporal fixation flows from Kojima, who said, at this year’s Comic-Con, “After five or 10 years, people will start to evaluate what it was about.” He was talking about Death Stranding, which released earlier this month but which I can scarcely deliver a definitive verdict on until at least 2024. In the meantime, I have revisited Metal Gear Solid 3 with a simple question: how has it changed in the 15 years since its release?

Well, for one thing, considering the game was given a “15” certificate by the BBFC, it’s now old enough to play itself—an image that would greatly please its creator, whose games are not so much inward-searching as self-devouring. I can draw out at least three layers of reflexive meaning from the subtitle alone. First, it refers to the survival-driven necessity to dine on local produce. Second, to the mission itself: to terminate—though not actually to eat—the Cobra Unit, an elite squad of soldiers that have defected to the Soviet Union. And the third meaning, more slyly concealed, relates to our hero, who is code-named Snake and whose symbolic role within the game, ripe for deconstruction, is chewed over and swallowed by the story.

Snake’s former mentor, a woman referred to as The Boss, leads the Cobras in their defection, slithering behind the Iron Curtain with two nuclear warheads. Thus she betrays not only her country but her former protégé. Snake ventures into a region of Russia called Tselinoyarsk, and that’s as far as firm setup goes. Collecting concrete information from a Kojima plot is a process that demands (a) a pot of black coffee, (b) a folder full of notes, and (c) to be carried out in a state of jabbering frenzy resembling those who pore sceptically over the Warren Commission Report. It’s also entirely beside the point. Kojima’s games pour forth in a heady stew of images, clueing you into the themes that coil throughout; anything more logical is surplus to requirements, and the images themselves don’t even need to make sense.

Take the Cobra Unit, for instance, whose members are possessed of unnatural powers and abstract nouns. There is The Pain, a man wreathed in a haze of hornets, which he waves into combat like a conductor. Or consider The Fear, who scuttles up the trunk of a tree like a spider, his forked tongue tasting the air. One of the unit, called The Sorrow, is a ghost, with skin like paper and an eye that weeps blood. None of these images—which have lingered, like screen burn, on my brain—are given anything as vulgar as an explanation. Why spoil it? It can’t have crossed Kojima’s mind for more than three seconds that there aren’t any tropical jungles in Russia, before it was waved away as a minor, inconvenient detail.

And thank goodness it was; Tselinoyarsk remains an unblemished epic of a setting. I’ve revisited it twice in recent months. First, as part of the Metal Gear Solid HD Collection, in which the colours—the entire array of reptilian shades—are sharpened, and the camera clings to Snake’s back, granting you fresh licence to swivel and swoon to your heart’s content. And second, with Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater 3D, on the Nintendo 3DS. This version’s greatest coup is not, as you might have guessed, the 3D effect—which sends the foliage bristling across your eyeballs, courtesy of the console’s stereoscopic rendering. Nor is it the portability, an advantage that allows you to peck off chunks of its world to play in idle pockets of time. The best thing about this version is also the most boring: the light cluttering of quality-of-life upgrades.

The bottom screen is given to the game’s vital functions: Snake’s food, facepaints, camouflage, equipment, and, most important, a map of each area, constantly visible. This has the curious effect of reminding you that Tselinoyarsk is, despite appearances, rather blocky and bolted-together. Both versions, in their way—be it bringing the place into fine focus or refitting it with optional extras—reveal the skeleton of old design. The previous games in the series, with their square layouts, have been half-digested—the rigid dusted over with the rugged. Unlike the hard grey hangars and corridors of the previous Metal Gear Solid games, icy and unbreached by nature, this is steamy, awash with febrile green—the sort of place where loyalties, like insects, might creep unchecked and vanish into the undergrowth.

Is it possible that Kojima purposefully uprooted and replanted his series in the jungle just to prime us for a tale infested with treachery? Maybe, but I wouldn’t be the least bit surprised if it turned out that the move was made purely to secure a contract with the game’s composer, Harry Gregson-Williams. After scoring Metal Gear Solid 2: Sons of Liberty, Gregson-Williams was asked about the possibility of a follow-up, to which he replied, “If it’s set on an oil rig outside New York then no, but if it’s set in the Amazon, then maybe.” Et voilà: Tselinoyarsk—not quite the Amazon, but close enough, and, crucially, on Russian soil. On the strength of the soundtrack, it was well worth the move.

Another stealth classic, Splinter Cell: Pandora Tomorrow, came out the same year as Snake Eater—just eight months before—and it boasted, among other things, music composed by Lalo Schifrin. I’m still convinced there was a mix up in the post, and that both men were pleased with the result and kept quiet all these years. Pandora Tomorrow bears the hallmarks of Harry Gregson-Williams: the airy military-industrial ambience, and the synthetic thuds of percussion. Snake Eater, on the other hand, is filled with flute and electric strings, with Snake’s creeping heels nipped by pizzicato. It has the swing of sixties espionage, fried by the fear of nuclear destruction and submerged, above all, in stealth. Sound escapes the smear of time in a way that graphics can’t, (Playing on the 3DS, I wore headphones, and practically felt the greenhouse fug) and the sonic pleasures of Snake Eater don’t end with the music.

The isle is full of noises. Kojima, along with his co-writers Tomokazu Fukushima and Shuyo Murata, takes comfort in the drum-tight rhythm of military sentences. The first moments of the game, showing Snake parachuting into the jungle, spark with terms like “CAVOK,” meaning “Cloud and Visibility OK”; “Bailout Bottle,” referring to an emergency oxygen tank used by divers; and, of course, “HALO jump,” which means “high altitude – low opening” but also rings the hero with the aura of an angel. (Hence the instruction, given by Snake's commanding officer, Major Tom, to “spread your wings and fly,” just before Snake begins a Miltonian fall to Earth. What better way to begin the tale of a man, spread over the course of several games, whose patriotism wanes and wends toward darkness?)

There are more digestible details that require no explanation, like “external temperature minus 46 degrees celsius” and, as Snake’s commanding officer informs him, “You’ll be falling at 130 miles per hour.” What’s going on here? Is it sheer nerdiness, film-crazed logorrhoea, or something more? One thing that occurred to me in recent playthroughs is that this language, doused in data, has its roots in fear and a craving for order and safety. In similar fashion to Aaron Sorkin, Kojima seems soothed by statistics, by the rise and fall of sentences suffused with numbers and their inherent hardness. Is it any wonder that the series’ longtime hero is called Solid Snake? Or that the name of his arch-nemesis is Liquid Snake, as if the gravest threat is that the firm and the fixed might dissolve, that order might liquesce into chaos?

The charge often levied at Kojima is that such obsessive reverence for military hardware is fetishistic. Look no further than the sex-charged scene in which Eva bestows upon Snake not a kiss but a gun—for him a far more romantic proposition. So much so that he begins spouting lusty lines, as though he were composing a sonnet: “The feeding ramp is polished to a mirror sheen / And the interlock with the frame is tightened for added precision.” Well, no one likes a loose interlock. But in a game, and a series, so gripped by the awful glow of the atomic bomb, such flights of fanciful detail feel less like fetishisation and more like the expressions of a desperate need for security—the beating of a boyish retreat into toys and tradecraft.

In one of those pleasing accidents—or blessed cosmic alignments—I happened to watch the BBC production of Smiley’s People, which follows the frosted obsession of its protagonist, a master spy named George Smiley (played, with unhurried precision, by Alec Guinness), as he pursues his nemesis, Karla, the head of Moscow Centre. One scene, where Smiley speaks to an old ally, captures the Cold War in six brief sentences. “It’s not a fighting war, not like in our day. It’s grey. Half-devils versus half-angels. Nobody knows where the goodies are.” And then, a shard of blasphemy: “Karla could be right. Have you ever thought of that?” Metal Gear Solid 3 bears about as much stylistic relation to Smiley’s People as Michael Bay does to Anton Chekhov, but what it does share is the instinctive feel for the temper and texture of its time.

“Scholars tell us that the first spy in history was the snake in the Book of Genesis,” Eva says, but despite the biblical framework, Snake Eater is stripped of moral bite; it is more concerned with the slow-acting venom that has struck its hero, and in coaxing us to his eventual cause. “The enemies we fight are only in relative terms,” says The Boss, “constantly changing with the times.” Nowhere in the game is this better explored than with the character of Ocelot, the hothead with the ice-pale complexion and a crew cut the colour of milk, who remains likeable despite his beret, and even warms to Snake. Though he is a villain, and makes for one of the series’ best boss fights, he and Snake share a camaraderie—that of opposing soldiers whose superiors seem a distant, dwindling thought, a million miles from the battlefield. In Tselinoyarsk, ideologies turn idle.

As I write this, 15 years on and three weeks after finishing Death Stranding, it occurs to me that Kojima’s fixations haven’t been touched, all that much, by time. “It feels like there are lots of walls and people thinking only about themselves in the world,” he said recently, in an interview with the BBC. His solution, in Death Stranding, is to bring the disparate places of the world together in a united network of high-speed information. In Metal Gear Solid 3, he demonstrated the same point—that the boundaries between countries are faint and friable—with greater subtlety. We know, having played the subsequent Metal Gear Solid games, that Snake’s solution to such meaningless demarcations, and the bloodshed that erupts from such borders, is to splinter off and strand himself in isolation, holding off for the times to change, waiting to come in from the cold.